Earlier this week, Ilan Stavans asked: Is there a Jewish literary renaissance? He will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

Sometimes when I’m congratulated for writing well, the praise comes with a sense of theft, as if someone like me who has spent decades in academia — I started teaching when I was just out of college — should be expected to say things in muddy, incomprehensible ways.

I understand the qualm. Academics are known for their pedantic style. This is particularly the case in the humanities, where, given the universal topics, one would expect the opposite. Scholars for the most part write obscurely for a small audience — minuscule, really: less than half a dozen peers. To show off, they become convinced that arguments need to be labyrinthine and the language unintelligible.

This awful mode is learned in graduate school. Unfortunately, judging by the sample of the latest crop of scholars, there doesn’t appear to be an end to this education to obfuscate.

Truth is, it isn’t a matter of style. The problem, in my opinion, is the fear to be honest, to say what one thinks elegantly and persuasively when the occasion prompts. In other words, this handicap is related to the fear of speaking one’s mind. Graduate school, again in the humanities, is a hindrance: it teaches future teachers to hide behind cumbersome theoretical frameworks. The pleasure to read, to write, to think is sabotaged by the obligation to align oneself behind a doctrine.

Yes, I’m convinced academics are timorous people, I’m not sure if more or less than everyone else, but in our case it shows because of the privileged position in which we find ourselves. Given the extraordinary opportunity to speak out, they burry their head underground. Academic freedom is wasted on academics.

Feeling suffocated, I have sought role models outside academia as well as in the liminal zone where the classroom and the outside world meet: Edmund Wilson, Lionel Trilling, Irving Howe, Henry Luis Gates, Jr., Morris Dickstein… That is, I have tried to follow figures capable of simultaneously speaking to two audiences, the one within and the one outside campus.

Each of them has responded to the needs of his time. What they’ve shown — to me, at least — is that the dividing line between insiders and outsiders is nothing if not artificial. The two audiences exist only in our mind. When we exile them from there, these become one.

To write well is to express oneself with clarity, precision, and conviction. And to be humble: one must irrevocably assume the reader — all readers — to be our equals. To think otherwise is an exercise in solipsism.

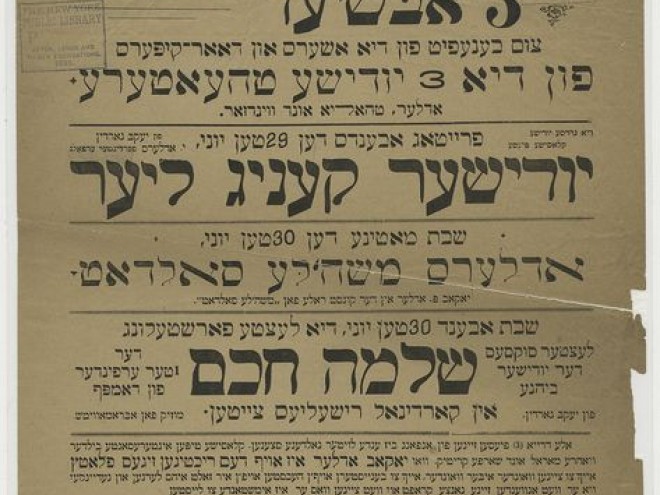

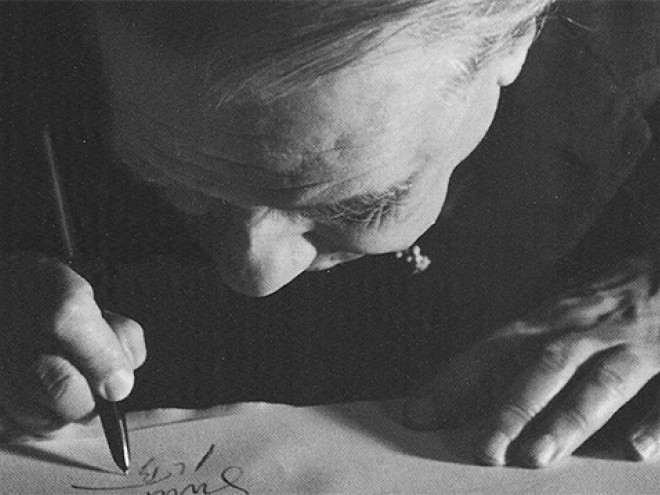

Ilan Stavans is Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College. His most recent books are the collection of essays Singer’s Typewriter and Mine: Reflections on Jewish Culture (University of Nebraska Press, 2002) and the graphic novel El Iluminado (Basic Books, with Steve Sheinkin).

Ilan Stavans is the internationally known, New York Times bestselling Jewish Mexican scholar, cultural critic, essayist, translator, and Amherst College professor whose work, translated into twenty languages, has been adapted into film, theater, TV, radio, and children’s books.