These days, when people write a book, they invariably have an acknowledgments page, where they thank a few people or – like someone going on and on at the Oscars – everyone they ever knew, down to the babysitter who once braided their hair in elementary school. My own acknowledgements page for my most recent book thanks my first readers – the friends who commented on my stories in draft – and the artist colonies that offered me an extended time to write.

These days, when people write a book, they invariably have an acknowledgments page, where they thank a few people or – like someone going on and on at the Oscars – everyone they ever knew, down to the babysitter who once braided their hair in elementary school. My own acknowledgements page for my most recent book thanks my first readers – the friends who commented on my stories in draft – and the artist colonies that offered me an extended time to write.

Now that I think about it, and think about it in terms of what really enabled me to do what I needed to do, I realize I should also have thanked New York’s Tenement Museum. The museum consists of a modern visitor center at 103 Orchard Street and a tenement at 97 Orchard that has been “restored” – or perhaps safely kept in its earlier dismal condition. The rooms have been furnished as they were during the years (1863−1935), when the tenement was occupied.

This may sound drearily like any number of museums, where you stand behind a rope while you look at a Victorian bedroom or see the trundle bed where Melville’s children slept. But it is nothing of the sort. Instead the tour guide who takes you into 97 Orchard Street (you can’t just wander alone) tells you the story of one of the immigrant families who once lived there. And at least some of those immigrants were Jewish.

The Museum gave me the very thing that I needed to write: a sense of the lived life, the specifics of daily existence. I have at times got buried in, and distracted by, my efforts at verisimilitude. I have tried to do research for books and only learned how much I don’t know, how there was no way I could write my book unless I had more courage, more of an ability to ask people who I didn’t know what their  lives were like. But intruth you don’t need to know everything to write a story or novel. You just need enough to convince. In an interview on identitytheory.com, the fiction writer Jim Shepard talks about the role of research in fiction this way:

lives were like. But intruth you don’t need to know everything to write a story or novel. You just need enough to convince. In an interview on identitytheory.com, the fiction writer Jim Shepard talks about the role of research in fiction this way:

Henry James said, ‘She had eyes like this and a nose like this.’ And you go, ‘I could really see her.’ You have two details! Theoretically you could do the same thing with the Battle of Antietam, right? If you get the right details. Part of the point of all that research is not, ‘Oh, I am going to be able to deploy more details.’ It’s that I am more likely to come across those two.”

What The Tenement Museum gave me were the details, ironically enough, to imagine where my characters lived. I only used two things from the visit to the Museum: a detail about where toilets were placed in a tenement and what the lay out of an apartment might be like, but, in my head, the whole world was quite vivid. I could see it all, and hopefully my readers can as well.

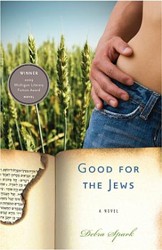

Debra Spark is the author of The Pretty Girl, a collection of stories about art and deception. She has been the recipient of several awards including a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. She is a professor at Colby College and teaches in the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College.