Earlier this week, Leslie Maitland wrote about artist Gunter Demnig’s Stolpersteine project and reconnecting branches of her family separated by the Diaspora of the Nazi years. She will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

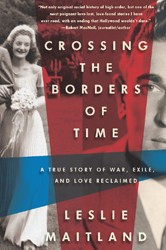

I have always been fascinated by epigraphs — those borrowed words that authors choose to introduce and encapsulate the message of their books. And so, almost as soon as I started writing my own book, Crossing the Borders of Time, I found my thoughts exploring several possibilities, words whose power had won them space in my catalogue of memory.

I have always been fascinated by epigraphs — those borrowed words that authors choose to introduce and encapsulate the message of their books. And so, almost as soon as I started writing my own book, Crossing the Borders of Time, I found my thoughts exploring several possibilities, words whose power had won them space in my catalogue of memory.

The book involves a search to find my mother’s long-lost love, the young and handsome Frenchman she’d left behind in 1942, when — fleeing the Nazis—she was forced to board the last refugee ship to escape France before the Germans sealed its ports. She was Jewish and 18; he was Catholic and 21. “Whatever the length of our separation, our love will survive it, because it depends on us alone,” Roland had written to Janine in a farewell note before she sailed. “I give you my vow that whatever the time we must wait, you will be my wife.” But war and disapproving family had intervened, and even as she tried to build a different life than the one she had imagined, Mom shared with me her longing for the love that had been stolen from her.

The story of their star-crossed romance, culminating in my efforts to reunite the pair, first called to mind Bob Dylan’s paean to a young love that endures:

The future for me is already a thing of the past.

You were my first love and you will be my last.

Yet even in my silent reading, the gnarly twang of Dylan’s unique delivery resounded as unreservedly American. It set the wrong mood as the opener for a love story that unfolded in Europe of the war years, and its tone seemed too lighthearted for the period and the harrowing experiences I was depicting. Besides, Dylan belonged to my youth. His rebellious ballads could be interpreted as a rejection of my parents’ generation. Indeed, the disdain that he expressed was not lost on my father, who actually forbade me to play Dylan’s albums on his phonograph, as if their scathing lyrics might damage the machinery.

Next in top contention for my epigraph were favorite verses from T. S. Eliot’s “Burnt Norton,” the first of his Four Quartets:

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose-garden. My words echo

Thus, in your mind.

The Nobel Prize – winning poet had completely captured the spirit of my story, as he spoke to how a past, imagined yet never lived, nonetheless persists in memory. The words that echoed in my mind, entrancing and enthralling me since childhood, were all my mother’s words — her stories from a rose-garden, a lovers’ garden, an Eden from which she had been exiled. Perfect. Except for one disturbing thing. Eliot, whose philosophical poetry I adored, was a reputed anti-Semite, as exemplified most clearly in his early work.

Could I comfortably enshrine the verses of an anti-Semite on the opening pages of a volume that I had devoted in large measure to describing the plight of European Jewry in the Holocaust? I struggled with the question. To make Eliot’s voice my book’s first voice felt like treason. A betrayal of the millions who had suffered and died for no other reason than their Jewishness. And yet it grated, in banishing the artist, to have to sacrifice the art – a dilemma far from new to us. We are used to squirming as we read literary classics from times and places in which loathing for the Jewish people was a cultural prejudice quite shamelessly expressed. Surely, I argued with myself, we cannot be expected to reject all the works where Jews appear unfavorably or whose authors are anti-Semites. And what about music? Must we always close our ears to Richard Wagner?

Even now, after months of debate with myself and with others whose opinions I respect, my answers to these questions feel muddled. Before my book went to print, however, and not without regret, I relinquished T. S. Eliot and wondered whether, had I written something different — a physics text on the nature of time, for example — I might have felt more free to honor his creative voice by quoting him in my epigraph.  As it was, in place of Eliot’s verses, I finally chose a cherished line from Thomas Wolfe:

As it was, in place of Eliot’s verses, I finally chose a cherished line from Thomas Wolfe:

O lost, and by the wind grieved, ghost, come back again.

It had the virtue of calling to mind for me the loss not only of Roland, but also of my father, who had died before the lovers reunited, and of Hitler’s countless victims. Beyond that, when my son asked me whether Wolfe, as well, might have been a secret anti-Semite, I was happy to assure him that while the great novelist had visited Germany repeatedly in the 1930s, he had publicly denounced the Nazis’ treatment of the Jews. Retaliating, the Nazis had banned his books in Germany. Wolfe’s longtime lover, I suddenly remembered then, had been a Jewess named Aline Bernstein. To her, “A.B.,” he dedicated his masterpiece, Look Homeward, Angel, from which I drew my epigraph with the sense I had arrived at the right place.

Leslie Maitland is a former award-winning reporter and national correspondent for The New York Times who specialized in legal affairs and investigative reporting. Her newest book, Crossing the Borders of Time: A True Story of War, Exile, and Love Reclaimed, is now available.