Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

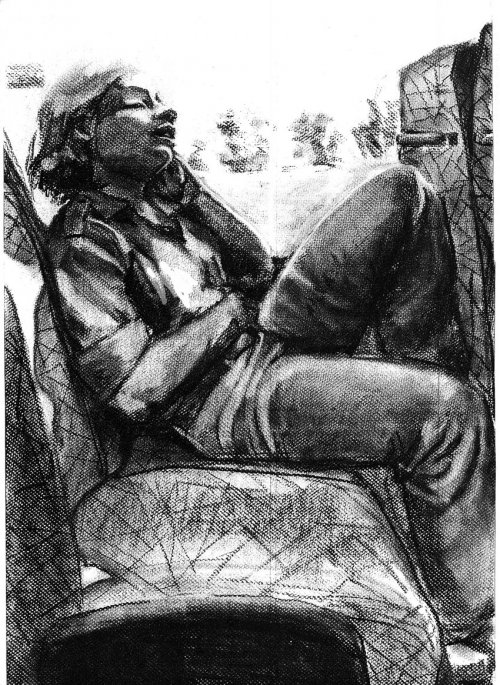

People have remarked that there’s a whole lotta bus ridin’ in jobnik. Even in the issue where Miriam is on furlough in the US and Canada, she spends a page riding a bus. Why?

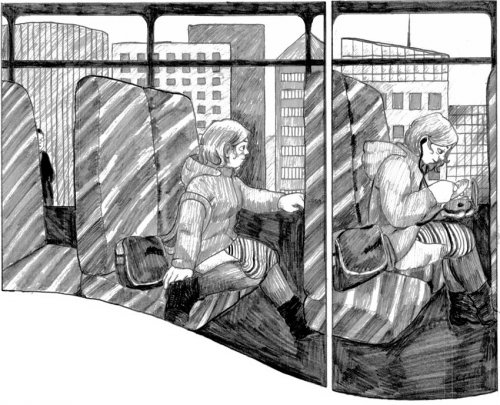

Firstly, there was a whole lot of bus riding in my life at that time. I specifically asked for and got a permanent assignation “far from home,” meaning where you don’t go home every day. I was further from home than most; I lived in Jerusalem and served on a base about 30 minutes from Eilat, the southernmost tip of Israel. Each Sunday and Thursday, I spent 6 hours in transit, not counting local Jerusalem buses.

You may know that a soldier in uniform with proper ID can ride any bus or train for free in Israel. This is true, with the exception of the entire southern triangle of Israel, between Be’er Sheva and Eilat. Apparently, this area is too remote, too sparse, or in the case of Eilat, too touristy for a soldier to have a reason to go there without paying. Soldiers who serve or live in this area need to carry a special “Arava card” to be able to travel free on southern buses (Arava is the desert south of the Negev). This is just to illustrate that my service was bus-filled even by IDF standards.

One challenge of cartooning about my army service is that most of it was really, really boring. Somehow I need to depict tedium without being tedious; hopefully having a bus scene a couple times an issue gives you the feeling that that was indeed how a big chunk of my life was spent.

But Egged buses are also symbolic. To me, buses are a limbo state between identities. You aren’t anybody when you travel alone on a bus. If you’re listening to music and staring out the window, as I prefer, you’re practically disembodied. One of my favorite things to do was to get off at my layover in Be’er Sheva, walk across to the street to the mall, buy a magazine and order a fancy salad at a cafe. I relished that in my uniform, reading a magazine and eating a salad alone, I could be anybody. (Being from a large family, and growing up Orthodox in Columbus, Ohio where there weren’t any kosher restaurants, means I still feel like a woman of mystery when I eat at a restaurant alone.)

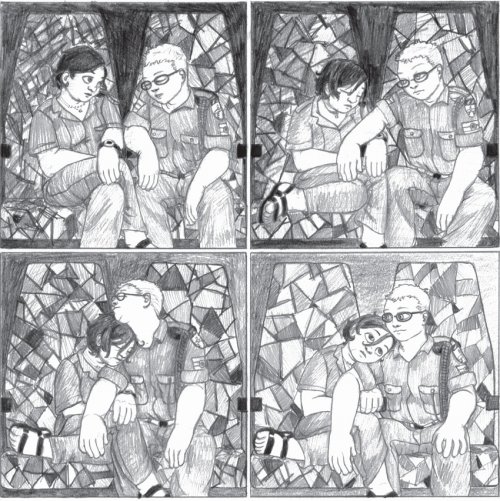

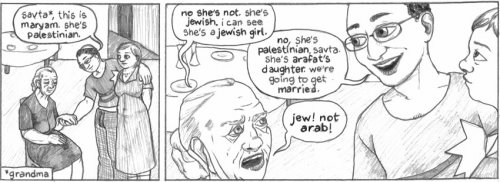

jobnik, as a proper bildungsroman, is about identity, trying to find identity, trying on and discarding identities. Israelis join the army at 18 after graduating high school, so almost everyone still lives with their parents whenever they’re not on base or in combat. I think this is an even more extreme condition of toggling between adulthood and childhood than the traditional American one of going away to college (I lived with my sister who was close to me both in age and emotionally, but there was a lot of my army life I kept hidden).

I noticed that not just I, but every soldier I knew, was a different person at home and on base. One of my favorite illustrations of this was when I visited my friend Yossi for Shabbat. He was a flamboyant, in-your-face gay man on base, while at home with his Orthodox Sephardic family, he was a twice as aggressively flamboyant gay man. Then out at gay clubs, he was practically demure. Clearly, the transformations had to take place on the public transportation between these spaces.

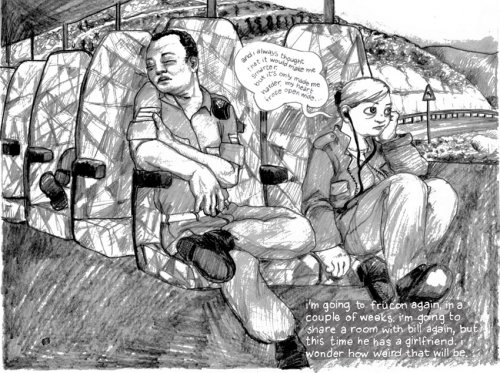

When I had that two-week furlough six months into my service, I spent it in Columbus, Toronto and NYC. I planned it that way because I had stuff to do in all three places, and bus-riding was so thoroughly entrenched in my identity, maybe I thought I couldn’t go two weeks without it. The bus rides from Toronto to New York, and then Manhattan to Poughkeepsie, were also significant for me at the time. In the first case, I spent twelve hours on a bus, and then learned when I disembarked that my parents had been frantically phoning and emailing people on both sides, because they had expected me in New York a day earlier. This reinforced my belief that when I was out of sight of people who knew me, I ceased to exist. Which was comforting, given how painful existing often is.

Going to Poughkeepsie in the middle of the night wasn’t an adventure; it was exile from the proper Orthodox world of my sister and her new boyfriend. I thought that after my longest bus trip ever, I would be able to stay still somewhere. But I barely had time to unshoulder my giant backpack before I found out my slutty girl cooties had to sleep several counties away, to preserve tzniut.

That’s the drawback of having a transitional identity, not properly belonging anyplace; sometimes people call you on it, and make you leave.

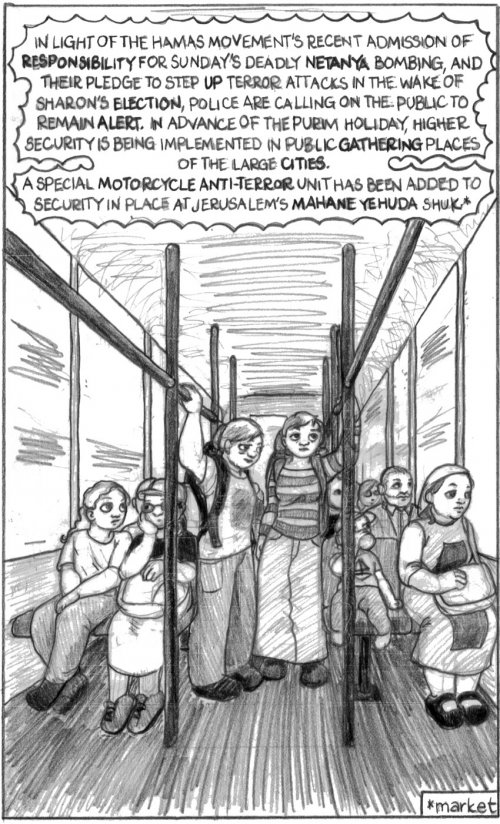

Then, of course, there’s terrorism. Blown up and upended like a whale skeleton is how most non-Israelis think of Egged Buses, the ones who do think of Egged buses. The second intifada started in jobnik! issue 2, here at jobnik! issue 8, it’s the following March. Suicide bombings haven’t really begun in earnest yet, but they’re coming.

Miriam Libicki has been writing and drawing the self-published comic book, jobnik!, since 2003. She will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

Miriam Libicki is a graphic novelist living in Vancouver Canada. Her 2008 Israeli Army memoir “jobnik!” has been used in over a dozen university courses. She teaches cartooning and illustration at Emily Carr University of Art and Design. She also makes a line of hand-silkscreened shirts and met her husband while following a nerd-folk band on tour.