Lesléa Newman is the author of 60 books including her most recent book, October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard. She is blogging here today for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

“And you shall lay down, and no man shall terrify you….” Whenever I stand up in shul on Shabbat and recite those words from the prayer for peace, I am transported back in time to 1998, and across many miles to Laramie, Wyoming.

“And you shall lay down, and no man shall terrify you….” Whenever I stand up in shul on Shabbat and recite those words from the prayer for peace, I am transported back in time to 1998, and across many miles to Laramie, Wyoming.

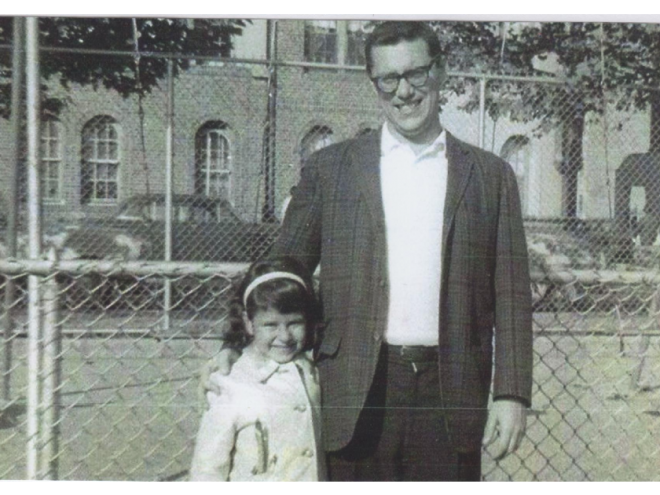

It was October, and I was all set to travel out west as the keynote speaker for Gay Awareness Week at the University of Wyoming. My bags were packed, and my speech was written. “Heather’s Mommy Speaks Out: Homophobia, Censorship, and Family Values” focused on the difficulties I had in getting my book Heather Has Two Mommies published, and how important it is for every child to see a family like his or hers reflected in a piece of literature. As a Jew growing up in the 1950’s, I knew what it was like to read books about children trimming the Christmas tree and looking for the Easter bunny. Books like Sammy Spider’s First Hanukkah and A Mezuzah on the Door had not yet been written. Growing up without seeing a family like mine in a book or movie or on a TV show made me feel like I didn’t belong. There was no place for me.

As a child, I couldn’t articulate my need to see someone like myself reflected back at me by the culture at large, let alone do something about it. As an adult, I could write books for children whose families were considered “different” so that they did not feel so alone.

But two days before I was to step on the plane, Jim Osborn, the head of the University of Wyoming’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered Student Group called. He told me his friend Matthew Shepard, who was also a member of the LGBT group, had been kidnapped, robbed, beaten mercilessly, tied to a fence, and left to die. He was discovered 18 hours later by a biker, and was now in the hospital, in a coma. Jim knew that Matt being attacked right before Gay Awareness Week started was not a coincidence. “I would understand it if you wanted to cancel your appearance,” Jim said to me.

The words that flashed through my mind were: If I am not for myself, who am I? If I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when? Jim seemed to think that any speech I could give would have a healing effect on his community. As a Jew, I take the job of tikkun olam very very seriously. So I told Jim that I had every intention of being there.

A few days later, as I gave my speech, my eyes kept wandering to an empty seat in the front row of the auditorium. I pictured Matthew Shepard sitting there. I had seen his picture in the newspaper. I knew he had been on the planning committee for Gay Awareness Week. I knew he had planned on being at my presentation. Instead he had died that very morning, killed by two men who hated him merely because he was gay.

I have always felt that the pen is mightier than the sword. And so I wrote an essay called “Imagine” in honor of Matthew Shepard and have read it aloud to start off every college presentation I have given since my trip to Laramie. But I knew there was more that I could do. In the past few years, many young people who were bullied for being perceived as being gay had taken their own lives. How to stop the bullying and the suffering? What more could I do? As a published author, I had a voice that people listened to. With this gift comes an obligation. Tikkun Olam. The responsibility of repairing the world.

On the tenth anniversary of Matthew Shepard’s murder, members of the Tectonic Theatre project, who had gone out to Laramie right after Matt’s murder to conduct interviews to create their theatre piece, The Laramie Project, returned to interview the people of Laramie once more. On the eleventh anniversary of Matt’s death, I attended a performance of The Laramie Project — Ten Years Later: An Epilogue. That night I couldn’t sleep. The words of my mentor, Grace Paley, echoed through my mind: Write what you know you don’t know about what you know. I knew a lot about what had happened to Matthew Shepard. I also knew there was a lot that I didn’t know. And so I picked up my pen. Immediately, a thought entered my brain: use your imagination to create fictional monologues from the silent witnesses of the crime, like the fence, the moon, the wind, and the stars. That’s crazy, I thought to myself. But then I remembered the words of another of my mentors, Allen Ginsberg: first thought, best thought. And with that in mind, I let the words flow out of my pen. I knew that I would never know what happened to Matt that night. He wasn’t around to tell me. And the two men who killed him have recounted the events in ways that contradicted each other. Even if I could speak to them, I could not rely upon them to tell the truth. And so, I called upon the silent witnesses of the hate crime to tell me what they knew: the truck Matt was kidnapped in, the fence he was tied to, the moon that looked down upon him, the deer that kept him company all through the night. I trusted my imagination to create these fictitious monologues, to tell me what I knew I didn’t know. I wrote 67 poems that explore the impact of Matt’s murder, but when I came to the end of the narrative, I felt something was missing. The book was intended for a teen audience, too young to remember Matt Shepard. How to end such a book without devastating my young readers?

I knew that I would never know what happened to Matt that night. He wasn’t around to tell me. And the two men who killed him have recounted the events in ways that contradicted each other. Even if I could speak to them, I could not rely upon them to tell the truth. And so, I called upon the silent witnesses of the hate crime to tell me what they knew: the truck Matt was kidnapped in, the fence he was tied to, the moon that looked down upon him, the deer that kept him company all through the night. I trusted my imagination to create these fictitious monologues, to tell me what I knew I didn’t know. I wrote 67 poems that explore the impact of Matt’s murder, but when I came to the end of the narrative, I felt something was missing. The book was intended for a teen audience, too young to remember Matt Shepard. How to end such a book without devastating my young readers?

I knew the only way to find out how to end the book was to return to Laramie. Jim Osborn took me around town, to the bar from which Matt was abducted, to the courthouse where his murderers stood trial, and finally to the site where Matt had been beaten and abandoned. I stood at the fence, and hoping G‑d would understand, counted the ground, the sky, the wind, two hawks that flew overhead, a pile of snow, several tufts of grass, and myself as a minyan in order to say Kaddish for Matthew Shepard. I placed a stone from my own garden on the fence to show that someone had been there and that Matt had not been forgotten. I sang “Oseh Shalom” with tears streaming down my cheeks, and when I got on the plane to return home, the last poem of the book came to me. Of course the book had to end with a prayer. A prayer for a better world. For all of us.

PILGRIMAGE

The land was sold and a new fence now stands

about fifty yards away. People still come to pay

their respects. — Jim Osborn, friend of Matthew Shepard

I walk to the fence with beauty before me

The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want

I walk to the fence with beauty behind me

Yit’gadal v’yit’kadash

I walk to the fence with beauty above me

Om Mani Padme Hum

I walk to the fence with beauty below me

Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit

I reach the fence surrounded by beauty

wail of wind, cry of hawk

I leave the fence surrounded by beauty

sigh of sagebrush, hush of stone

OCTOBER MOURNING: A SONG FOR MATTHEW SHEPARD. Copyright © 2012 by Lesléa Newman.

Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.