Earlier this week, Melissa Fay Greene wrote about the adoption of her daughter, Helen, from Ethiopia, and telling jokes at church. Her new book, No Biking in the House Without A Helmet, is now available.

My husband and I are white people. We shop at R.E.I. for the clothes. We have cousins on both sides who are vegans and have attended more than one bean-filled wedding reception. We could move to Dubuque, Iowa, or Bangor, Maine, if we wanted to, without anyone wondering what on earth we were thinking. If pulled over by a traffic cop for a moving violation, we await him at our driver’s side window with the wide-eyed innocent-looking expectation that the exchange will proceed cordially and without undue suspicion. We are well-acquainted with the many bonuses of what is known on the street as White Skin Privilege.

We were born just this side of the mid-20th-century, to Jewish parents, when ethnicity was on the verge of being accepted as an acceptable American lifestyle. Jerry Lewis, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion of Israel, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, Danny Kaye, and Sammy Davis, Jr., were major Jews of our childhood. We weren’t told about the Holocaust.

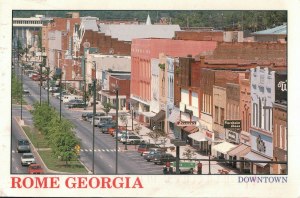

In 1980, my husband Don Samuel and I, newlyweds, moved to Rome, a northwest Georgia hill-town that hadn’t gotten the news yet that ethnic people were just regular folks. “Where y’all from?” everyone asked us. Our new neighbors asked us, the landlord asked us, the Big Boy’s waitress asked us, the filling station man asked us. The people down the street whose car had a bumper sticker reading, “Oil Yes, Jews No,” did not ask us.

In 1980, my husband Don Samuel and I, newlyweds, moved to Rome, a northwest Georgia hill-town that hadn’t gotten the news yet that ethnic people were just regular folks. “Where y’all from?” everyone asked us. Our new neighbors asked us, the landlord asked us, the Big Boy’s waitress asked us, the filling station man asked us. The people down the street whose car had a bumper sticker reading, “Oil Yes, Jews No,” did not ask us.

We’d moved to Rome, Georgia, from Athens, Georgia, after Donny graduated from the UGA School of Law, but our Rome questioners — “Where y’all from?” — felt perplexed rather than satisfied when we replied, “Athens.” “Athens?” said the Big Boy’s waitress, squinting at us. “Y’all Greeks?”

A variation on “Where y’all from?” was offered by citizens who had once accidentally seen a Woody Allen movie. Those people knowingly asked, “Y’all from New York?” It made us not want to confess that Donny was from New York.

No matter how we hedged, saying we were from Athens, mentioning that I was born in Macon and that Donny used to work in Brunswick and that we’d gotten married in Savannah, everyone had a sure-fire follow-up question. “Well, what church do y’all go to?”

Then we had to say it: “We’re Jewish.”

“Yeah,” they said. Then everyone — everyone — everyone asked the same thing: “Do y’all know the Essermans?” The mailman asked, the waitress asked, the Dunkin Doughnuts guy asked, the roofer asked.

We had moved to Rome the previous Thursday; no, we hadn’t met the Essermans yet.

A few years earlier, when researching my first book, Praying for Sheetrock, on the wooded Georgia coast, I’d fallen prey to similar interrogations. The rural black people of McIntosh County accurately sensed that, for obscure reasons, I was not part of the local white power structure, and they accepted that. They welcomed me warmly. The local white people, however, with similar intuition, wondered what I was hiding. In the middle of a an interview with the city attorney, the ruddy big-faced man interrupted me, leaned forward across his kitchen table, and asked, “Melissa? Do you know Morley Safer?”

A few years earlier, when researching my first book, Praying for Sheetrock, on the wooded Georgia coast, I’d fallen prey to similar interrogations. The rural black people of McIntosh County accurately sensed that, for obscure reasons, I was not part of the local white power structure, and they accepted that. They welcomed me warmly. The local white people, however, with similar intuition, wondered what I was hiding. In the middle of a an interview with the city attorney, the ruddy big-faced man interrupted me, leaned forward across his kitchen table, and asked, “Melissa? Do you know Morley Safer?”

“Morley Safer?”

“Morley Safer.”

“The anchor on the TV program, 60 Minutes?”

“That’s the fella. You know him?”

“No, I don’t know him.”

“Unh hunh,” he said skeptically.

I had no idea what he was driving at. We pushed on. A few minutes later he interrupted me again, leaned forward even more confidingly, and probed: “Melissa, do you know Jesus?”

Now I saw where we were headed. “No, I don’t know Jesus,” I said, “and I don’t know Morley Safer either.”

Now, in Rome, it was the Essermans everyone asked about. But it turned out that asking Jews if they knew the Essermans made a lot more sense than asking them if they knew Morley Safer or Jesus. The Essermans had immigrated from Latvia in the late 19th century, joining an already-thriving antebellum Rome Jewish Community. Two Esserman brothers opened Esserman’s Department Store on Broad Street in 1896, where it would last for most of a century: a beautiful clothing store with perfume displays and jewelry counters, a children’s department, men’s wear, ladies’ wear, and formal wear, without which the local citizenry might have dressed themselves in overalls made out of feed sacks or, worse, plaid country-club slacks. An Esserman cousin, Joseph Esserman, opened the Lad & Lassie children’s clothing store. The Essermans, short solid people with smooth round heads and thick enthusiastic eyebrows, instantly embraced Donny and me as landsmen, gave us the family discount at the store, included us in the weekly card games attended by other Essermans, and gave us gifts of large oil paintings of Eastern European village scenes created by the living patriarch, Hyman Esserman. We spent most of our two years in Rome, Georgia, hanging out with people forty and fifty years our senior. Because they were Jews.

We immediately joined Rodeph Shalom, a congregation founded in 1875 (its first rabbi had been an Esserman). The handsome hilltop brick synagogue with white pillars had been built in 1937. Until 1955, the temple had had a fulltime rabbi. Now a Reform student rabbi flew to town twice a month from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati to lead Shabbat services. She stayed in a motel owned by a couple from India who referred to her as the Rib-Eye. There were about 30 Jews in Rome when we lived there, and a sprinkling of non-Jewish spouses. Several curious local people attended services, too. The moment Donny and I walked into the building for the first time, the entire congregation turned around and breathed, as one: “YOUNG people!” Within the week, Donny was on the board and I was president of Sisterhood. After our very first Friday night service, we invited our newest friends, Oscar and Ruth Borochoff, to come home with us for a piece of cake. I guess they were in their seventies. The moment they entered our house, Mrs. Borochoff stepped into our tiny kitchen, put on an apron, and insisted on washing the dinner dishes still soaking in the sink. I had to drag her in embarrassment into the living room. These were the nicest people in the world.

We immediately joined Rodeph Shalom, a congregation founded in 1875 (its first rabbi had been an Esserman). The handsome hilltop brick synagogue with white pillars had been built in 1937. Until 1955, the temple had had a fulltime rabbi. Now a Reform student rabbi flew to town twice a month from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati to lead Shabbat services. She stayed in a motel owned by a couple from India who referred to her as the Rib-Eye. There were about 30 Jews in Rome when we lived there, and a sprinkling of non-Jewish spouses. Several curious local people attended services, too. The moment Donny and I walked into the building for the first time, the entire congregation turned around and breathed, as one: “YOUNG people!” Within the week, Donny was on the board and I was president of Sisterhood. After our very first Friday night service, we invited our newest friends, Oscar and Ruth Borochoff, to come home with us for a piece of cake. I guess they were in their seventies. The moment they entered our house, Mrs. Borochoff stepped into our tiny kitchen, put on an apron, and insisted on washing the dinner dishes still soaking in the sink. I had to drag her in embarrassment into the living room. These were the nicest people in the world.

When these coiffed, belted, perfumed ladies showed up at my house for the first Sisterhood meeting of my presidency, I, age 27, suggested that we become a branch of Amnesty International. They liked the idea very much. On our second meeting, I handed out literature about the iron-fisted military dictatorship of President Augusto Pinochet of Chile. Then we all wrote letters on behalf of Chilean political prisoners. The ladies wrote with flowing penmanship on scalloped pink stationary. “Dear Mr. Pinochet,” wrote one, “I am just so very disappointed to hear about this behavior.”

Donny and I lived in Rome when Mel Brooks’ History of the World: Part I came out. It didn’t open in Rome, though. Porky’s opened in Rome. People lined up to see The Cannonball Runin Rome. Caddyshack was wildly popular in Rome. Chariots of Fire did not open in Rome. We had to drive an hour and a half out of the Blue Ridge Mountains, across the clean rivers and past the discount carpet outlets, to the traffic-clogged state capital of Atlanta to see movies with Jews in them. In the famous closing sequence of History of the World Part I—“Jews in Space” — space shuttles shaped like Jewish stars, with Kosher written in Hebrew along the wings, whiz across the solar system, while rabbis peer anxiously out of their windshields through binoculars and then do some Israeli dancing. The Jews are in space, they sing with Yiddish accents.

They’re zooming along, protecting the Hebrew race.

The Jews are in space.

If trouble appears they’ll put it right back in its place…

“If this movie ever comes to Rome, people won’t understand this part,” we told our friends in Atlanta as we exited the theater.

“Whenever they sing, ‘The Jews are in space,’” said our friend Allen Baverman, “they’ll need a subtitle that says, ‘The Essermans are in space.’”

Our next-door-neighbor in Rome, a railroad man and Viet Nam vet named Steve Long, couldn’t delineate what about us was urban, what was college-educated, and what was Jewish. He was fascinated by every aspect of our lives (like why we subscribed to the New York Times instead of the Rome News-Tribune which carried the day’s TV listings and boy scout announcements) but it was the Jewish angle that intrigued him the most. He drove Donny all over North Georgia in search of a box of Passover Matzo that spring. While Donny tried to explain to yet another grocery store manager what exactly he was looking for, Steve leaned over and confided, man to man: “It’s some kind of Jew food.” He popped in one day when we were steaming artichokes for dinner. He got that strange half-smile on his face he got whenever he knew he was approaching something really peculiar. He donned an oven mitt, lifted the pot lid, and sprang back in shock. He returned to stand in the steam, sadly regarding the artichokes for a long minute, replaced the lid, and turned to face us. “I know, I know,” he said, already chuckling and putting up his hands in self-defense. “It’s Jew food.”

Something is gained, of course, in the increasingly widespread acceptance of ethnicities in America, in the mushrooming of small restaurants with international cuisine, in the rainbow-hued classrooms of American children, in the Babel of tongues heard on the streets even of moderate-sized and small cities, and in the fact of Republican politicians trying to use words like chutzpah. Actually, a lot is gained. We’re all the richer in this country. If anything at all is lost, I guess it’s the way we 20 or 25 Jews in Rome — almost as far out of our element as Mel Brooks’s Jews in Space — embraced one another, laughed together, gathered — the entire community — under one roof to make a seder, to kindle a menorah, to celebrate our daughter Molly’s baby-naming. Far from the Latvian-Jewish world left behind by the Essermans, and from the Lithuanian-Jewish world left by my grandparents, we made a Jewish village in Rome, Georgia. Sometimes it takes a shtetl.

Melissa Fay Greene has been blogging all week for the Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning’s author blogging series.

A two-time National Book Award finalist and winner of the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, the Hadassah Myrtle Wreath Award, the ACLU National Civil Liberties Award & other honors, Melissa Fay Greene is a current Guggenheim Fellow, a regular contributor to The New York Times Magazine, and a frequent guest on NPR.