Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

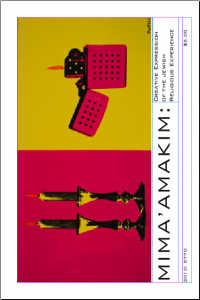

Aaron Roller is an editor of Mimaamakim, a journal of Jewish religious poetry and art. Their new issue was just released. He will be blogging all week for the Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning’s Author Blog.

The very notion of creating one magazine to house “Jewish poetry” doesn’t seem to make any sense. Jews wrote poetry in medieval Spain. Other Jews wrote Yiddish poetry as the Enlightenment made its way to Eastern Europe. There were poets among the early Zionists, just as there were among early Jewish immigrants living in New York’s Lower East Side.

The very notion of creating one magazine to house “Jewish poetry” doesn’t seem to make any sense. Jews wrote poetry in medieval Spain. Other Jews wrote Yiddish poetry as the Enlightenment made its way to Eastern Europe. There were poets among the early Zionists, just as there were among early Jewish immigrants living in New York’s Lower East Side.

What justifies grouping these seemingly disparate poets together? They wrote in different languages, in different forms about different topics. They range from the the greatest defenders of faith to those who struggled with belief to those who gave up on G‑d completely.

So what is Jewish poetry?

While not every poem written by someone who’s born a Jew counts as Jewish poetry, there is a larger conversation linking Jewish poets beyond a mere accident of birth. An awareness of Jewishness (whether manifested as pride, guilt or piety), a questioning of what it means to be Jewish, a feeling of interconnectedness with other Jews throughout both time and space and the willingness to employ (or inability to avoid) Jewish references (whether Biblical, liturgical or philosophical) all mark a Jewish poet.

Consider Allen Ginsberg, one of the most famous American poets of the last century, and a Jew more likely to chant “Hare Krishna” than “Shema Yisroel.” And yet, when faced with the death of his mother, Ginsburg responded with a poem entitled “Kaddish.” Ginsberg’s “Kaddish” jumps between fragmentary recollections of his mother’s life as a Jewish girl on the Lower East Side (“… I walk toward the Lower East Side — where you walked 50 years ago, little girl”), his own overheated experience (“I’ve been up all night, talking, talking, reading the Kaddish aloud, listening to Ray Charles blues shout blind on the phonograph”) and an appeal to G‑d (“Take this, this Psalm, from me, burst from my hand in a day, some of my Time, now given to Nothing – to praise Thee – But Death”).

By attempting to make sense of the traditional prayer of mourning and put it into his own terms, Ginsberg enters the conversation of other writers (and mourners) who have tried to understand the Kaddish (other American poets who have written poems called “Kaddish” include Charles Reznikoff and David Ignatow). By recollecting his mother’s life, Ginsberg is placing her — and, by extension, himself — within the larger Jewish experience.

What we’ve tried to do with Mima’amakim is to show you the variety, the strength and the diversity of Jewish poetry today. The new issue include poems and stories in three languages, and writing and art from writers from four continents, and of all different ages and religious backgrounds.

The new issue of Mimaamakim is now available. Come back all week to read Aaron Roller’s blog posts on the Visiting Scribe.