Jonathan B. Krasner is the author of the National Jewish Book Award winning title The Benderly Boys and American Jewish Education. Krasner was also a finalist for the 2012 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. He will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

One of the greatest dilemmas I faced while writing The Benderly Boys & American Jewish Education was how to refer to the group of Jewish educators who were mentored by New York Bureau of Jewish Education director Samson Benderly. At first glance the answer seemed deceptively simple. Benderly referred to his protégés as my “boys,” and the moniker “Benderly boys” was widely used both by members of the group and their colleagues in the field.

One of the greatest dilemmas I faced while writing The Benderly Boys & American Jewish Education was how to refer to the group of Jewish educators who were mentored by New York Bureau of Jewish Education director Samson Benderly. At first glance the answer seemed deceptively simple. Benderly referred to his protégés as my “boys,” and the moniker “Benderly boys” was widely used both by members of the group and their colleagues in the field.

And yet, the appellation is problematic. For one thing, in today’s world the term “boy” or “girl” when used in reference to a grownup has taken on a pejorative, or at the very least, a paternalistic connotation. This usage has largely become anachronistic, a relic of the “Mad Men” and “Driving Miss Daisy” era.

More fundamentally, the term “Benderly boys” is misleading. Although the majority of Benderly’s disciples were men, the group also included a number of women. A few attained leadership positions in schools, community centers, camps and other organizations. And while most voluntarily “retired” after marriage or the birth of their children, a few became career women long before the feminist revolution. Libbie Suchoff Berkson, for example, directed Camp Modin, in Canaan, Maine, while Elsie Simonofsky Chomsky served for many years as the principal of Gratz College’s well regarded Hebrew teacher’s program, the School of Observation and Practice. Still other women gave up leadership positions but continued to wield influence in the field. Rebecca Aaronson Brickner, who served as Benderly’s veritable right hand during his early years at the New York Bureau, officially left education in 1919 when she married Rabbi Barnett Brickner. But her influence continued to be felt in the religious school of Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue Temple (later called the Fairmount Temple), where her husband spent much of his rabbinical career. Likewise, Mamie Goldsmith Gamoran and Elma Ehrlich Levinger published dozens of religious school textbooks, storybooks and other educational materials years after they supposedly embraced domestic life.

Benderly, apparently, did not hesitate to apply the ‘Benderly boy’ appellation to his female disciples. In my book, I discuss the implications of this curious usage. Benderly reflexively used gender as a marker for his closest disciples. If you fulfilled his criteria, which included studying at Columbia Teachers College, assuming administrative responsibilities at the Bureau or one of its affiliated schools, and attending his daily, early morning schmooze sessions, you were considered one of the boys, regardless of your anatomical make-up. Contemporary scholars, however, have been less sanguine about using the term “Benderly boys,” with some preferring gender neutral terms like “group” or “bunch.”

The term “Bureau bunch” was adopted in the 1910s by the larger team of workers at the New York Bureau, while the inner circle of disciples referred to themselves as Chayil , an acronym for the Hebrew phrase “education is our national foundation,” and a word meaning valor or virtue. While I intersperse the term “Benderly group” throughout the book for the sake of variety, I will admit to finding neither “Bureau bunch” nor Chayil compelling. The latter seemed obscure and, in any event, was confined in the day to an exclusive group of insiders. I wished to cast a wider net. The latter, meanwhile, was irredeemably hokey-sounding, particularly in the ear of one who was raised on a seemingly continuous loop of Brady Bunch reruns.

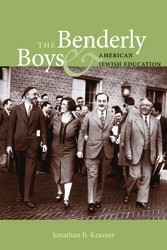

In the end, I decided to stick with “Benderly boys,” despite its drawbacks, and not merely due to its alliterative appeal. For me, the use of the appellation by Samson Benderly and its embrace by his disciples was decisive. By retaining the term “Benderly boys” I felt that I was at once remaining true to history while also honoring the memories of these men and women. But I did not entirely give up on the desire to problematize the designation. That is why I was thrilled to come across a crisp photograph of Benderly walking arm in arm with three of his closest disciples, including Libbie Berkson, while working at the American Jewish Archives. I knew immediately that it needed to adorn the book’s cover. This photo of Libbie, surrounded by men, but clearly accepted as a full member of the Benderly team, juxtaposed with the book’s title, is purposely discordant and meant to induce perplexity. Here was a case where a picture could truly speak louder than words.

Here is hoping that the publication of The Benderly Boys (along with Carol Ingall’s 2010 volume, The Women Who Reconstructed American Jewish Education) helps to encourage a rediscovery of Benderly’s “girls.”

One of the greatest dilemmas I faced while writing The Benderly Boys & American Jewish Education was how to refer to the group of Jewish educators who were mentored by New York Bureau of Jewish Education director Samson Benderly. At first glance the answer seemed deceptively simple. Benderly referred to his protégés as my “boys,” and the moniker “Benderly boys” was widely used both by members of the group and their colleagues in the field.

One of the greatest dilemmas I faced while writing The Benderly Boys & American Jewish Education was how to refer to the group of Jewish educators who were mentored by New York Bureau of Jewish Education director Samson Benderly. At first glance the answer seemed deceptively simple. Benderly referred to his protégés as my “boys,” and the moniker “Benderly boys” was widely used both by members of the group and their colleagues in the field. And yet, the appellation is problematic. For one thing, in today’s world the term “boy” or “girl” when used in reference to a grownup has taken on a pejorative, or at the very least, a paternalistic connotation. This usage has largely become anachronistic, a relic of the “Mad Men” and “Driving Miss Daisy” era.

More fundamentally, the term “Benderly boys” is misleading. Although the majority of Benderly’s disciples were men, the group also included a number of women. A few attained leadership positions in schools, community centers, camps and other organizations. And while most voluntarily “retired” after marriage or the birth of their children, a few became career women long before the feminist revolution. Libbie Suchoff Berkson, for example, directed Camp Modin, in Canaan, Maine, while Elsie Simonofsky Chomsky served for many years as the principal of Gratz College’s well regarded Hebrew teacher’s program, the School of Observation and Practice. Still other women gave up leadership positions but continued to wield influence in the field. Rebecca Aaronson Brickner, who served as Benderly’s veritable right hand during his early years at the New York Bureau, officially left education in 1919 when she married Rabbi Barnett Brickner. But her influence continued to be felt in the religious school of Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue Temple (later called the Fairmount Temple), where her husband spent much of his rabbinical career. Likewise, Mamie Goldsmith Gamoran and Elma Ehrlich Levinger published dozens of religious school textbooks, storybooks and other educational materials years after they supposedly embraced domestic life.

Benderly, apparently, did not hesitate to apply the ‘Benderly boy’ appellation to his female disciples. In my book, I discuss the implications of this curious usage. Benderly reflexively used gender as a marker for his closest disciples. If you fulfilled his criteria, which included studying at Columbia Teachers College, assuming administrative responsibilities at the Bureau or one of its affiliated schools, and attending his daily, early morning schmooze sessions, you were considered one of the boys, regardless of your anatomical make-up. Contemporary scholars, however, have been less sanguine about using the term “Benderly boys,” with some preferring gender neutral terms like “group” or “bunch.”

The term “Bureau bunch” was adopted in the 1910s by the larger team of workers at the New York Bureau, while the inner circle of disciples referred to themselves as Chayil , an acronym for the Hebrew phrase “education is our national foundation,” and a word meaning valor or virtue. While I intersperse the term “Benderly group” throughout the book for the sake of variety, I will admit to finding neither “Bureau bunch” nor Chayil compelling. The latter seemed obscure and, in any event, was confined in the day to an exclusive group of insiders. I wished to cast a wider net. The latter, meanwhile, was irredeemably hokey-sounding, particularly in the ear of one who was raised on a seemingly continuous loop of Brady Bunch reruns.

In the end, I decided to stick with “Benderly boys,” despite its drawbacks, and not merely due to its alliterative appeal. For me, the use of the appellation by Samson Benderly and its embrace by his disciples was decisive. By retaining the term “Benderly boys” I felt that I was at once remaining true to history while also honoring the memories of these men and women. But I did not entirely give up on the desire to problematize the designation. That is why I was thrilled to come across a crisp photograph of Benderly walking arm in arm with three of his closest disciples, including Libbie Berkson, while working at the American Jewish Archives. I knew immediately that it needed to adorn the book’s cover. This photo of Libbie, surrounded by men, but clearly accepted as a full member of the Benderly team, juxtaposed with the book’s title, is purposely discordant and meant to induce perplexity. Here was a case where a picture could truly speak louder than words.

Here is hoping that the publication of The Benderly Boys (along with Carol Ingall’s 2010 volume, The Women Who Reconstructed American Jewish Education) helps to encourage a rediscovery of Benderly’s “girls.”

Jonathan B. Krasner will be blogging here all week.

Jonathan Krasner is the Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Associate Professor of Jewish Education Research at Brandeis University. A finalist for the Sami Rohr Prize in Jewish Literature, he is also a two-time National Jewish Book Award winner for The Benderly Boys and American Jewish Education (2011) and Hebrew Infusion: Language and Community at American Jewish Summer Camps (2020).