Ilan Stavans is Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College. His most recent books are the collection of essays Singer’s Typewriter and Mine: Reflections on Jewish Culture (University of Nebraska Press, 2002) and the graphic novel El Iluminado (Basic Books, with Steve Sheinkin). He will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

I hear repeatedly that Jewish literature is undergoing a renaissance. The statement puzzles me.

I hear repeatedly that Jewish literature is undergoing a renaissance. The statement puzzles me.

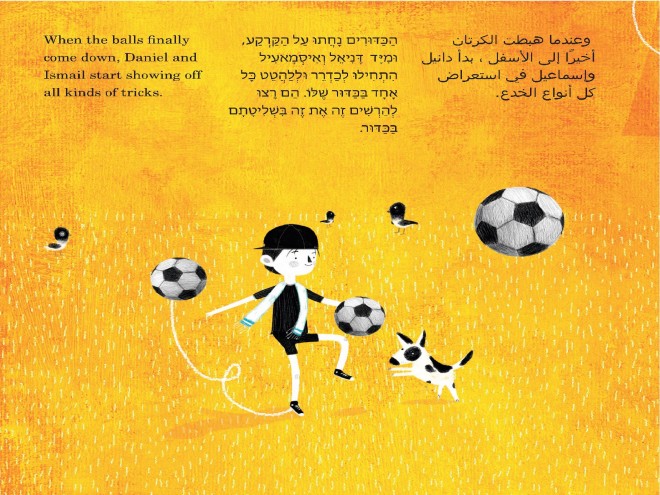

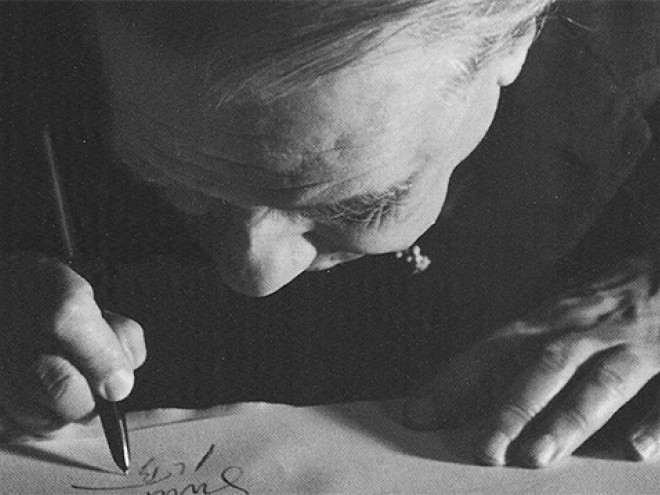

I can’t think of a period over our last 3,000 years of history — yes, since the Bible began to take shape as a compendium of folktales — when Jews haven’t been part of a literary renaissance. We’re always dying…and leave a record of our near extinction. Indeed, Jewish literature thrives because it is constantly said to be on its last stand.

We write the apocalypse: no sooner does someone announce our demise, we do everything possible to prove it wrong.

Ours, no doubt, are apocalyptic times. Not since 1945 has anti-Semitism been more noxious than it is now. All of us Jews are seen as parasites in countless places. The hatred against us wasn’t cured after the Holocaust; it simply went commando.

We’ll unquestionably survive the current climate of animosity, although not without casualties: we’ll be again be physically decimated, not to say psychologically bruised. It has taken us a long time to think ourselves out of the Holocaust. Our next survival will also require enormous stamina.

That’s the eternal cycle in which we’re actors. The theme of Jewish history — and its literature — is the dialectic between creation and destruction.

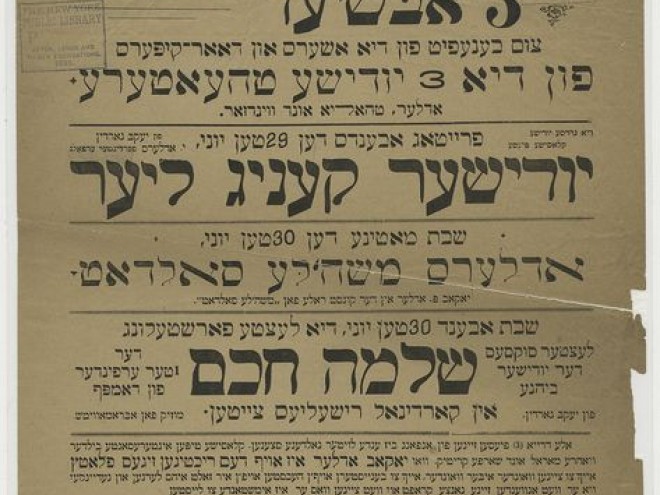

We’re textual creatures: our primary relationship with the world isn’t material but textual. We’re simultaneously authors and characters in a larger-than-life narrative. And texts connote languages. Every chapter in our history is delivered in another language. I don’t see a literary renaissance today in Spanish, French, Portuguese, Polish, Russian… Our current mode, our lengua franca, is English. In fact, English is

what Yiddish was a century ago: our portable homeland.

That habitat isn’t eternal; it will perish, just as others did before.

What puzzles me about the present-day literary renaissance is its hubris: American Jews believe they their sheer drive can overcome anything. Yet no diaspora in Jewish history has been more insular, and more monolingual too. Our literature is a testament to our arrogance.

A measured life is defined by the awareness of its own shortcomings.

Check back on Wednesday for Ilan Stavan’s next post for the Visiting Scribe.

Ilan Stavans is Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities, Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College, the publisher of Restless Books, and a consultant to the Oxford English Dictionary. Sabor Judío: The Jewish Mexican Cookbook, coauthored with Margaret E. Boyle, is a finalist in this year’s National Jewish Book Awards. And Otrarse: Ladino Poems of Juan Gelman was included by World Literature Today in the best translations of 2024. His new book, Lamentations of Nezahualcóyotl: Nahuatl Poems, is just out.