Earlier this week, Mike Silver introduced readers to boxing’s forgotten Jewish champions of the early twentieth century featured in Stars in the Ring: Jewish Champions in the Golden Age of Boxing: A Photographic History. Mike is guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

“Benny Leonard moved with the grace of a ballet dancer and wore an air of arrogance that belonged to royalty.” – Dan Parker

While researching the boxing careers and lives of the 166 champions and contenders featured in Stars in the Ring: Jewish Champions in the Golden Age of Boxing: A Photographic History, I constantly found myself moved by the commitment and courage displayed by these men as they struggled to master their unusual craft and succeed in such an unforgiving sport.

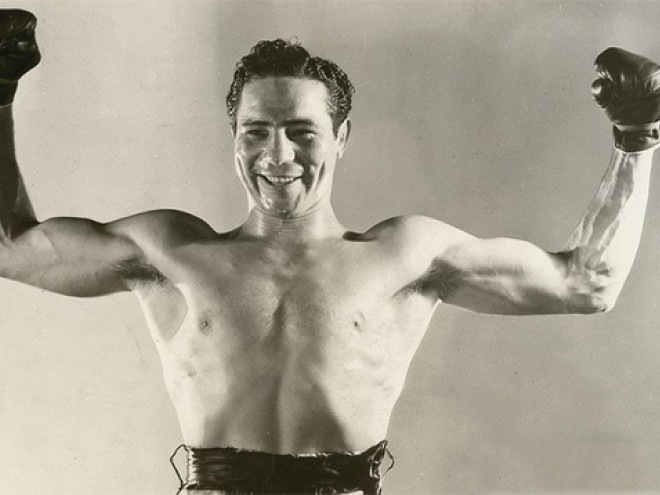

What I found remarkable was that a people with no athletic tradition to speak of, and who were perceived as lacking the qualities to succeed in such a violent and brutal sport, were able to produce hundreds of outstanding boxers, including nearly a dozen of whom rank among the greatest who ever lived. But if I had to  choose just one of these boxers on whom to focus, it would be the peerless Benny Leonard, lightweight champion (135 pound weight limit) from 1917 to 1925.

choose just one of these boxers on whom to focus, it would be the peerless Benny Leonard, lightweight champion (135 pound weight limit) from 1917 to 1925.

Benny Leonard is universally acknowledged to be among the ten greatest boxers of all time. As a young 120-pound amateur growing up on the Lower East Side of New York, he was thin and lacking in strength. Out of necessity he developed a speedy and elusive style in his early days as a boxer. As he matured and his frame filled out, Leonard developed a powerful punch to go along with his superb boxing skills. But no matter how strong he became, Leonard always considered his brain the most important weapon in his formidable arsenal.

Leonard was the first Jewish sports superstar of the mass media age, and one of the first Jewish American pop culture icons. He was written about and photographed more than any other Jewish entertainer or artist of his day, and his wholesome appeal went beyond the sport of boxing: he cultivated the image of a good Jewish mama’s boy who happened to be very good at punching people for a living. It was Leonard’s boast that no opponent could muss his hair in a fight. When Leo Johnson, the country’s outstanding black contender, attempted to unnerve Leonard by mussing his “patent-leather locks” during a clinch, the miffed champion flattened him in less than two minutes of the first round. (It was only the second time in over 150 bouts that Johnson had been stopped).

Leonard constantly strove for perfection. In his all-consuming desire to understand and master the art of boxing, he set about to deconstruct and analyze virtually every aspect of the sport. He also possessed a warrior’s spirit and was not averse, when the situation called for it, to throw caution to the wind and mix it up — but his nimble brain was always working overtime, seeking out the weaknesses in his opponent’s style. When asked by the famous trainer Ray Arcel why as a world champion he studied four-round preliminary fighters sparring in the gym, Leonard replied, “You can never tell when one of those kids might do something by accident that I can use.” To sharpen his alertness he would sometimes spar with two boxers at the same time; he studied human anatomy and was always careful never to waste a punch. The day after a fight he’d be back in the gym, talking over tactical mistakes.

Leonard was well-spoken: he once challenged philosopher Bertrand Russell to a debate as to the merits of boxing. He also took his responsibility as a representative of the Jewish people seriously, often boxing exhibitions to benefit both Jewish and Catholic charities.

Benny Leonard retired as undefeated champion in January 1925, at the age of 28. His face bore few scars despite his 191 professional fights — a testament to his brilliant defensive skills. A few days later an editor for the Hearst Newspapers wrote a column claiming that Benny’s reputation as champion and his numerous charitable contributions “has done more to evoke the respect of the non-Jew for the Jew than all the brilliant Jewish writers combined.”

For the next four years Benny enjoyed the fruits of celebrity and wealth, appearing in vaudeville and a Hollywood serial and investing in various business ventures using a portion of the nearly one million dollars he earned in the ring. Unfortunately, it all came to an end with the stock market crash in 1929 and the beginning of the Great Depression: Leonard’s fortune was wiped out and he was forced to make an ill-fated comeback in 1931 at the age of 35.

Of course there is more to this story, but the important part of the great fighter’s legacy had already been written a decade earlier. Benny Leonard will always remain the gold standard for every boxer striving to achieve perfection in the toughest of all sports.

Mike Silver’s work as appeared in The New York Times, Ring magazine, Boxing Monthly, and elsewhere. He has served as an historical consultant for 19 documentaries and curator for the 2004 exhibit “Sting Like a Maccabee: The Golden Age of the American Jewish Boxer” at the National Museum of American Jewish History.

Related Content:

- Jewish Mothers Never Die by Natalie David-Weill

- Douglas Stark: Researching Jewish Sports

- Marc Tracy: We Missed These Jewish Jocks — Do You Know Them?

Mike Silver is an internationally respected boxing historian and author whose work has appeared in The New York Times, Ring magazine, Boxing Monthly and various web sites. He was historical consultant for nineteen documentaries and curator for the 2004 exhibit “Sting Like a Maccabee: The Golden Age of the American Jewish Boxer” at the National Museum of American Jewish History.