Lesléa Newman is the author of 60 books including A Letter to Harvey Milk, Nobody’s Mother, Hachiko Waits, Write from the Heart, The Boy Who Cried Fabulous, The Best Cat in the World, and Heather Has Two Mommies. Her most recent book, I Carry My Mother, is now available. She is blogging here today for Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

“My cello is my oldest friend, my dearest friend.” – Pablo Casals

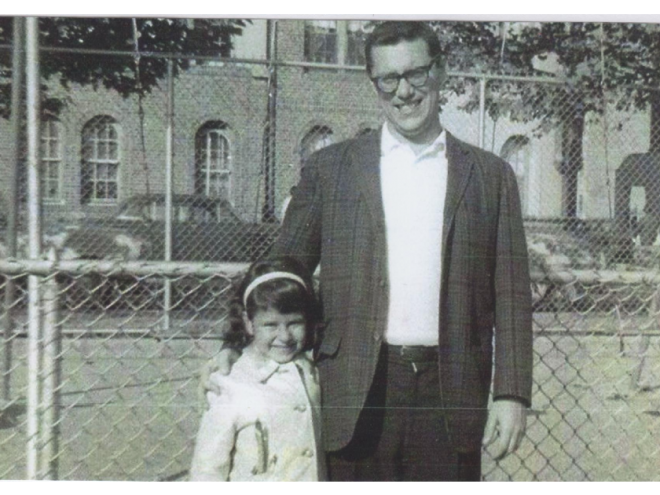

My pencil is my oldest friend, my dearest friend. We met when my family moved from a 60-unit apartment house in Brooklyn to a four-bedroom house on Long Island. I was eight years old and my world was shattered. In Brooklyn, I could walk to school, Aunt Gussie’s Candy Shop, Mrs. Stahl’s Knishes, and most importantly, to my grandmother’s apartment across the street for a kiss on the keppie and a nosh (her homemade blintzes were to die for). In my Long Island suburban neighborhood, there was nowhere to go. Nothing was in walking distance, and my mother, born and bred in Brighton Beach, had not yet learned to drive. After the bus dropped me off at the end of the school day, I was stuck in the house. The hours between then and the time my father came home from his office in the city and supper was served were endless. My mother watched what she called her stories — “As The World Turns” and “All My Children” — in the living room. My brothers played stickball in the street. And I retreated to my bedroom with a stack of books.

My pencil is my oldest friend, my dearest friend. We met when my family moved from a 60-unit apartment house in Brooklyn to a four-bedroom house on Long Island. I was eight years old and my world was shattered. In Brooklyn, I could walk to school, Aunt Gussie’s Candy Shop, Mrs. Stahl’s Knishes, and most importantly, to my grandmother’s apartment across the street for a kiss on the keppie and a nosh (her homemade blintzes were to die for). In my Long Island suburban neighborhood, there was nowhere to go. Nothing was in walking distance, and my mother, born and bred in Brighton Beach, had not yet learned to drive. After the bus dropped me off at the end of the school day, I was stuck in the house. The hours between then and the time my father came home from his office in the city and supper was served were endless. My mother watched what she called her stories — “As The World Turns” and “All My Children” — in the living room. My brothers played stickball in the street. And I retreated to my bedroom with a stack of books.

One day, having read everything I had carted home from the school library, I picked up a pencil and began to write. What emerged onto the pages of my black-and-white composition notebook was a long, sad story about a dog being hit by a car. Somehow I knew I needed to make myself cry over all I had lost: my friends, my neighborhood, my independence, a teacher I had especially loved, proximity to my adored and adoring grandmother. The little fluffy dog I killed off in my story was my ticket to my own grief. Alone in my room, I could cry over him, which I did both as I wrote the story and as I read it afterwards. And then strangely, I felt much better. And thus a writer was born.

My pencil kept me company through a lonely childhood, a difficult adolescence, and my tumultuous twenties when I struggled with an eating disorder. I never wrote because I had something to say. I always wrote to see what I had to say. And to this day, I do not write to be understood. I write to understand. Writing is how I make sense of the world: the world inside me, the world outside me, and the relationship between the two.

Though half a century has passed since I wrote the story of the little dog, in many ways I am still that sad little girl who uses her writing to make herself cry. This was especially evident two years ago when I found myself back in my childhood bedroom, having returned to take care of my mother who was suffering from two deadly diseases brought on by her lifelong love affair with nonfiltered Chesterfield Kings: bladder cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD). My mother was one tough rugeleh and she expected everyone around her to be tough as well. She insisted that she was fine and didn’t need help, even when her face clenched tight as a fist and she moaned in pain. (“I’m not moaning, I’m kvetching.”) One day, we struck a deal: she promised to tell me the truth about her illness — clearly she was not “fine” — if I promised not to cry. And once again I kept my feelings bottled up until I could creep upstairs to my bedroom where my pencil — my oldest friend, my dearest friend — awaited me. Every night for four weeks, I tucked my mother into the hospital bed we had set up in the living room, cleared away dishes of food she had no appetite for, shut the light, and tiptoed up the stairs. And there in my room, after I sobbed into my pillow so she wouldn’t hear me, I picked up my pencil and wrote a triolet, which is a French poetic form that contains a specific rhyme scheme and repetition pattern.

Why did I choose such a rigid form to write about my mom’s impending death? I didn’t pick the form; the form picked me. Like an old, dear friend, my pencil instinctively knew what I needed to get me through a time that was simply unbearable. The unyielding structure of the triolet not only held my poems together, it held me together. Focusing on rhythm, rhyme, repetition, and line breaks brought me closer to my own grief and distanced me from it at the same time. As I wrote — and rewrote and rewrote — the same words and phrases became a bell of sorrow resounding deep inside me, forcing me to confront what I so desperately wanted to deny. At the same time, focusing on form and struggling with the challenge of fitting all I was feeling into 8‑line stanzas with a prescribed pattern, gave me some distance from my emotions which offered a temporary respite from the deepest sadness I have ever known. Writing in this way took a lot of concentration. My pencil knew I had to use my head to pour out my heart. Like a true friend, my pencil saw what I needed and found a way to give it to me.

She was just here and now she’s just gone

In a New York minute I lost my mother

How can the rest of the world carry on?

She was just here and now she’s just gone

On whose loving breast will my head rest upon?

I’ll search all of my life but I won’t find another

She was just here and now she’s just gone

In a New York minute I lost my mother

Excerpted from “The Deal” © 2015 Lesléa Newman from I Carry My Mother, Headmistress Press, Sequim, Washington, 2015. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Related Content:

- Essays: Death, Mourning, and Loss

- Havoc: New and Selected Poems by Linda Stern Zisquit

- Handiwork by Amaranth Borsuk