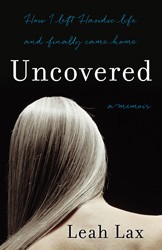

Leah Lax joined the Hasidic community when she was sixteen years old, leaving thirty years later and coming out as a lesbian. She shares her experience in her memoir, Uncovered: How I Left Hasidic Life and Finally Came Home, and in a series of posts here on The ProsenPeople as this week’s Visiting Scribe.

Friends kept sending me the links, her smiling face in my inbox again and again: stories about Faigy Mayer, who killed herself jumping off a New York building. I googled “ex-Hasidic,” not exactly a common term, and pulled up thousands of news sites around the world. Since I’m also ex-Hasidic, this seemed surreal.

I live in Texas. Mayer was from New Square, the same isolated hardcore Hasidic town that is the setting for Shulem Deen’s All Who Go Do Not Return. Both she and Deen were affiliated with Footsteps, a New York City organization that helps ex-Orthodox people adjust to secular society. Mayer and Deen were friends.

After she left them, Mayer suffered from the loss of family and friends. Mayer’s family and community shunned her; her mother even refused to share baby pictures. When she died, her family insisted she had been “bipolar and schizophrenic” and these allegations were all over the news. I wondered why a claim by people who had treated her so cruelly was given such credence. I knew that some Hasidic communities foist a label of mental illness on rebels, going as far as having them committed, hospitalized, and heavily medicated.

It turns out, this was done to Faigy Mayer as well.

Soon, Mayer blended in my mind with Sandra Bland, who died the same week not far from my Houston home. Both were pushed into apparent suicide by entrenched bigotry and cruelty.

It seemed that the press’s interest in both victims fizzled out after their past struggles with depression were revealed, as if their deaths were solved with this revelation of personal struggles. The weakness, the weak link, had been revealed. To me, it all sounded too much like the Blame the Victim/She Had It Coming stuff of old rape cases that nicely take the focus off the perpetrators, exonerating them by default. I wondered if the tone of the news coverage would have been different if they had been men.

In an op-ed for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Shulem Deen listed eight other friends who taken their own lives. “The journey away from ultra-Orthodoxy is so fraught that some simply don’t make it,” he said.

Which is where I paused and woke up from my obsession with Faigy Miller.

It’s a long story, the story of my leaving. I have to say here that group identity for Hasidim is a huge part of overall identity. Loneliness — the lack of a group that reflects your self — is particularly disorienting for us. Even though, because I was a closeted lesbian, I’d never really belonged, when the group was gone for me, I wasn’t sure any more that “I” was still there. Who was that? I was forty-five before I met another ex-Hasid, even older before I met another gay ex-Hasid.

A scene haunts me from that time. I was in a therapist’s office. My pain was so palpable it seemed to thicken the air, my language as fragmented as my life. The room was dim and spare. She was like a kind steady shadow. “I wouldn’t, I don’t think,” I told her, “but, I understand why people…do. It seems so possible, so logical, sometimes.” Suicide.

When I left the Hasidim after joining at the age of sixteen, in all that time I’d never held a remote control, didn’t know cable channels or the Internet, or how to figure a tip in a restaurant. I didn’t understand thirty years’ worth of cultural and historical references around me. But I still had a great satisfying sense of having come home, a thrilling, joyful second chance. I floundered at first, but held onto memories of having once been a confident teen at home in this society.

That’s the difference, why I’m okay, because I felt I’d come home. Most ex-Hasidim are forever in exile.

One of the first things I did when I decided to leave was call my mother. “Mom,” I said. “I’m leaving Levi, and the Hasidim, and taking off the wig. And Mom, I’m a lesbian.” There was a pause. Then she said, “Oh my God, you’re coming home.”

Leah Lax’s work has been published in Dame, Lilith, Moment, and Salon. Her memoir, Uncovered: How I Left Hasidic Life and Finally Came Home, is now available for purchase.

Related Content:

- Interview with Leah Vincent, author of Cut Me Loose

- Interview with Shulem Deen, author of All Who Go Do Not Return

- Leah Vincent: The Ultra-Orthodox Backlash

Leah Lax (MFA Creative Writing) is an author and librettist. Her first book was the award-winning Uncovered. Not From Here follows her journey back into society through listening to new immigrants tell their stories. In the process, she also uncovers the stories of her Jewish grandparents, and begins to understand who she is now as a Jew and an American.