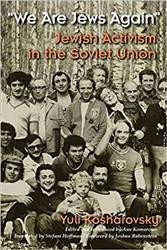

Alexander Smukler presents a samizdat copy of Exodus in Russian to author Leon Uris. Moscow, November 1989. Collection of Inna and Yuli Kosharovsky.

Jewish activism in the Soviet Union, supported by a movement to free Soviet Jewry abroad, resulted in a massive exodus. As Yuli Kosharovsky noted, concerning the late Soviet period and early 1990s, “In the years of mass emigration, the overwhelming majority of Jews — more than 1,500,000 people — left the borders of the former Soviet Union. The majority of those who left — around 900,000 — settled in Israel.” The struggle and its outcome were of massive historical proportions, and it seemed natural to many observers and advocates to use Biblical language when they demanded that the Soviet leaders “Let My People Go!” and when they spoke about the liberation of Soviet Jews from the grip of the “Red Pharaoh.”

Certainly, there were important geo-political factors at work in the events that unfolded leading to this massive exodus, many of which are detailed in “We Are Jews Again”. Against the backdrop of those forces and the high-level decisions and negotiations that took place, there was a core of more modest and incremental efforts that made the huge Aliya and revival of Jewish culture in the Soviet Union possible. Such grassroots initiatives included the work to make texts like Leon Uris’s 1958 novel Exodus available to Soviet readers in so-called “samizdat” (self-publishing). An early Zionist activist, David Drabkin, talked about translating Exodus with fellow activists Viktor Polsky and Vladimir Prestin for readers of Russian. At that time, in the late 1960s, Moscow was, as Kosharovsky wrote, a center for production and distribution of samizdat:

Moscow was a clearing house for samizdat distribution. Some books and printed material, including Leon Uris’s novel Exodus, were produced simultaneously in a few places. The quality of the translations and of the production work and the scope of samizdat distribution varied greatly. The movement was ripe for more effective coordination and division of labor.

The variety of translations of Uris’s novel – which appeared in samizdat editions as both Iskhod and Eksodus – may have been inevitable, given the powerful appeal it had for Soviet readers. Viktor Polsky recalled in his interview with Kosharovsky:

We received literature from the Baltics. Lea Slovin would come to us. David Drabkin had a channel. We … translated, copied, bound, and disseminated the novel Exodus. This book transformed my mother from a woman who had been intimidated by relentless persecution into a Zionist. For me, this was incontestable proof of the novel’s power to exert a strong emotional effect.

People recalled doing and reading 600+ page translations of Uris’s novel. The amount of labor that would have gone into producing that kind of samizdat text at home, with a typewriter and/or a photographic camera and prints developed in the bathroom, speaks to the feelings Uris’s novel inspired in Soviet readers. Others were moved to produce their own translations or slimmer adaptations. All accounts agree that Exodus was a central text of Jewish samizdat for activists and non-activists alike. Evidently, Uris’s tale about building and defending the state of Israel resonated profoundly with Soviet Jews who felt anxious for and then proud of Israel during the Six-Day War. That pride counterbalanced the often vicious anti-Israel propaganda from Soviet authorities. Moreover, Uris’s portrait of muscular, modern Jews resonated with qualities many Soviet Jews wanted to see in themselves, as it counteracted persistent negative stereotypes of cowardly Jews who shirked military service.

Alexander Smukler, pictured above with Uris, was one of those who helped expand the variety of material available to Soviet Jewish readers. Soviet Jewish samizdat included fictional works and poems from home and abroad, Hebrew language-learning materials, news bulletins and journals with articles and commentary on world events and administrative affairs. For example, the samizdat journal Jews in the USSR, initiated by Alexander Voronel and published from 1972 – 79, provided a crucial forum for Soviet Jews to reflect on their identity and concerns, in their own words and without the burden of official censorship. Smukler and a handful of others published the Information Bulletin on Issues of Repatriation and Jewish Culture, which appeared between 1987 and 1990, in Moscow. Foreign help – including the imaginative charge of Uris’s novel – mattered a lot for Soviet Jews. However, without the networks of readers and writers Soviet Jews created for themselves, working together to share stories, information, news and reflection, the revival of Jewish culture in the Soviet Union and the massive aliya would not have been possible.

Ann Komaromi is Associate Professor in the Centre for Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto. She is author of a book on underground novels in the Soviet Union, Uncensored: Samizdat Novels and the Quest for Autonomy in Soviet Dissidence (Northwestern University Press, 2015), which won the AATSEEL Award for Best Book in Literary/Cultural Studies. In 2015, she created the electronic archive “Project for the Study of Dissidence and Samizdat” for the University of Toronto Library Collections.