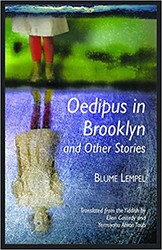

Earlier this week Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub wrote about their discovery of Blume Lempel’s transgressive Yiddish fiction, now translated into English as the collection Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories. Ellen and Yermiyahu are guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council all Week as part of the Visiting Scribe series.

Elena Ferrante may or may not be a certain Rome-based editor and translator, as has recently been alleged. What is clear is that whoever this writer is, they prefer to remain anonymous, to let the writing speak for itself.

Though Ferrante insists on remaining private as a person, her work reveals startlingly intimate truths about women’s lives. In this, the Italian writer has much in common with Blume Lempel, the author of the remarkable work we translated for the new collection Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories. While Lempel used her own name for most of her career she, too, opted for an unusual measure of personal privacy while reaching for an uncommon candor on the page.

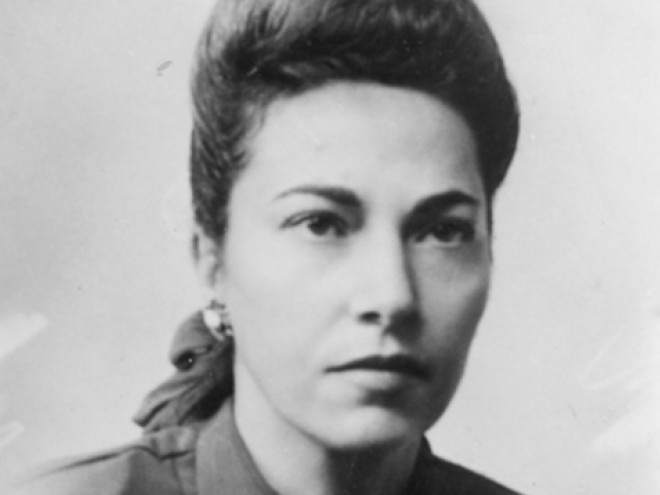

Lempel was born in Eastern Europe at the turn of the twentieth century in “a white-washed room by the banks of a river that had no name.” She lived in Paris for ten years before fleeing to the United States with the rise of Hitler. She settled in New York, where she turned out a prodigious amount of wonderfully original fiction until her death in the 1990s.

Like Ferrante’s, Lempel’s work was surprisingly frank and often undaunted by taboo. But even as she broke new ground in what she shared in her writing, she fiercely guarded her personal privacy. “I hide my literary existence under my apron,” she told an interviewer at her home on Long Island. “If you asked my neighbors about my writing, they’d look at you and think you were crazy.”

Would Lempel have been able to exercise the same artistic freedom if her neighbors had known she was writing about rape, incest, abortion, and the erotic imaginings of a middle-aged women, nursing mothers, and elderly widows? Probably not. Perhaps the concealing “apron” helped liberate her to explore such taboo themes.

Lempel’s decision to continue writing in Yiddish into the 1990s, even as the number of Yiddish readers dwindled year by year, also helped her control over what was public and what was not. Lempel was published in Yiddish publications throughout the world. She received multiple prizes and was admired by Yiddish writers and readers alike. Indeed, she sought out that recognition; at the same time, however, in many ways she held herself apart, pursuing her singular literary vision on her own terms.

Hiding is a recurrent theme in Lempel’s work. In one story, she writes about a mother and son living among the animals in the forest during the Holocaust; the account is so vivid that critics assumed it was drawn from personal experience, though it was in fact entirely the product of her extraordinary imagination and rare powers of empathy. In another story, a woman who has been raped and impregnated by her peasant rescuer during the Holocaust peeks out of the barn through a crack in the attic wall. “I live on the sidelines,” a different narrator reflects, “like a stranger in my own world.” In yet another story, a Jewish woman in German-occupied Paris works for the Resistance behind a carefully applied mask of glamour.

In preparing Oedipus in Brooklyn for publication, we spent many hours interviewing family members and reading Lempel’s correspondence and personal papers. We were curious about her artistic process, the rhythm of her days, and her reasons for choosing her subjects. Still, as an individual she remained mysterious to us — just as, it seems, she wished.

The paradox of privacy coupled with outspoken literary expression is hardly unique to Blume Lempel or Elena Ferrante. In fact, it is at the heart of the literary enterprise for many writers. What is notable for these two writers, however, is the starkness of the divide. During her lifetime, Lempel’s dream of an English-language readership for the most part eluded her. It’s a joy for us now to help her unrealized dream come true.

As we peel back the “veil” of Yiddish, allowing English-language readers gain access to Lempel’s dazzling prose and her bold approach to storytelling, we hope we enable this extraordinary writer to be known in the way she wanted to be known.

Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub received the Yiddish Book Center’s 2012 Translation Prize for their work on the fiction of Blume Lempel, now available to English readers in their collection Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories.

Related Content:

- Parnaz Foroutan: Soon I’ll Know All the Words They Know

- Josh Lambert’s Obscene Recommendations

- Nicole Loffler-Gladstone: Hopefully We’re on the Edge of a ‘Slut Lit’ Typhoon…

Yermiyahu Ahron Taub is the author of six books of poetry: The Education of a Daffodil: Prose Poems/Di bildung fun a geln nartsis: prozelider, A moyz tsvishn vakldike volkn-kratsers: geklibene Yidishe lider/A Mouse Among Tottering Skyscrapers: Selected Yiddish Poems, Prayers of a Heretic/Tfiles fun an apikoyres, Uncle Feygele, What Stillness Illuminated/Vos shtilkayt hot baloykhtn, and The Insatiable Psalm. Tsugreytndik zikh tsu tantsn: naye Yidishe lider/Preparing to Dance: New Yiddish songs, a CD of nine of his Yiddish poems set to music, was released in 2014. He was honored by the Museum of Jewish Heritage as one of New York’s best emerging Jewish artists and has been nominated four times for a Pushcart Prize and twice for a Best of the Net award.