with Daniel Estrin

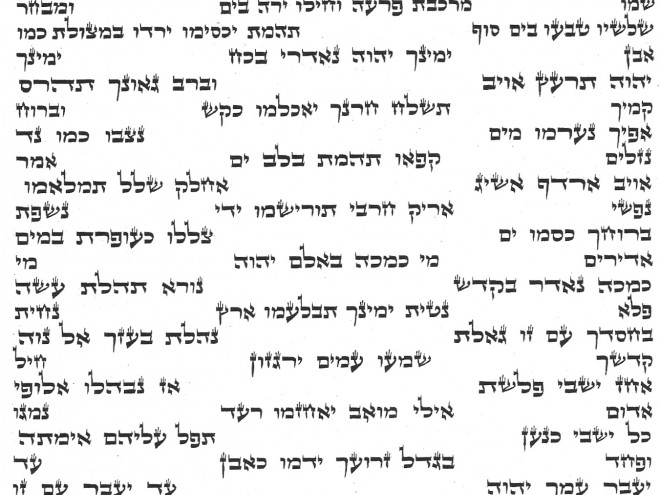

For Jewish Book Month, Jewish Book Council spoke with Chanan Tigay about his debut book, The Lost Book of Moses: The Hunt for the World’s Oldest Bible, about the author’s quest to find a lost biblical manuscript, and to solve the historical riddle of its alleged forger, nineteenth-century Jerusalem antiquities dealer Moses Wilhelm Shapira.

Daniel Estrin: Your book seeks to solve a real-life mystery of a lost ancient manuscript. How did you come across this story?

Daniel Estrin: Your book seeks to solve a real-life mystery of a lost ancient manuscript. How did you come across this story?

Chanan Tigay: I first heard of Moses Wilhelm Shapira from my father, a Bible scholar and rabbi who spent 15 years writing a commentary on the Book of Deuteronomy for the Jewish Publication Society. We were sitting around the Shabbat table one Friday night. I’m a journalist, and I started talking about some articles I had recently written — they had discovered Noah’s Ark again, which seems to happen at least annually. It was a team of Chinese Evangelicals this time, and they had come out with the news that they discovered wooden beams that had been a portion of Noah’s Ark on top of Mount Ararat in Turkey. It became a big story in the news, as it tends to be, and then within days, of course, a guy who had been a part of the expedition came forward and admitted that it was all a hoax. I was telling my family about some articles I had written about all this, and the interviews I was doing. When I was finished, my dad said, “Hey, speaking of Biblical hoaxes, there was this guy named Shapira who in 1883 showed up at the doorstep of the British Museum claiming to have the oldest copy of a portion of the Bible in the world.” And then he went on to tell the story in fairly light detail, because he knew the general outlines but he was not an expert on the case. Like many bible scholars, he knew the contours of the story — which immediately attracted me.

DE: That led to a four-year quest to solve the case. At what point did you decide to write a book about it?

CT: Initially, I was just interested in it the way I might be interested in astronomy. I didn’t necessarily think I was going to write about it. But being a journalist and a writer, there’s always that spark when you hear something interesting that gets you thinking, “Hey, that sounds like a good story.” And the more I dug, the more I realized this story had endless, unexpected twists and turns. At that point, I realized I could write something about this, but the initial thought was that it would be an article about the case. Very gradually, I came to the idea that it might actually be a book. I think that happened when I came to the realization that I wanted to hunt down Shapira’s missing Deuteronomy manuscript. At that point, it sort of solidified itself as an idea for a book.

DE: What has been the prevailing wisdom about Shapira’s scrolls and why did you doubt it?

The prevailing wisdom pretty much until today had been that Shapira himself had forged the manuscript of Deuteronomy — a very odd manuscript, I should add, with many, many variant readings from the traditional text of Deuteronomy, including a shuffling of the Ten Commandments, and the addition of a new commandment. The idea was that Shapira had forged this manuscript; that he tried to sell it to the British Museum; that he had been caught; that, humiliated over having been caught, he had killed himself; and then, once that happened, that the manuscript had made its way to Sotheby’s. Sotheby’s auctioned it off: it was purchased by a British book dealer named Bernard Quarich, and Quarich, it was believed, sold the manuscript to an English-Australian nobleman named Sir Charles Nicholson. Nicholson lived in Australia, but at the end of his life lived in the north of London. His large estate burned down in 1899, and, the thinking went, the great likelihood was that Shapira’s manuscripts went up in flames along with the rest of Nicholson’s home.

The more research I did, the more it seemed to me that this theory was, at best, unlikely — or that I could think of other possibilities of what had happened to Shapira’s scrolls that were at least as likely if not more so.

DE: There are other detectives out there who have been on this hunt, too. You mention a particularly dedicated one, an Israeli documentary filmmaker named Yoram Sabo. Why did you think you could find answers when others hadn’t?

CT: Initially, I didn’t. When I first met Yoram Sabo and he put out the faint possibility that he and I might work together, my instinct was to go for it. Because I felt like he had a 30-year head start on me, and there was no way I was ever going to catch up to him, that’s just seemed impossible. This guy was the Shapiramaniac as far as I could tell. He’d been searching for three decades at that point and so I didn’t think I was likely to be the one to find it. So I wanted to work with him. And ultimately that didn’t work out, so I was left with two possibilities: one was to quit, and the other was to say, hey, if he hasn’t found it in 30 years, maybe he’s not going to find it, and maybe what I need to do is start looking for different approaches, different angles from which to search, angles no one else has tried before.

DE: You traveled to seven countries, across four continents over the course of four years. Sometimes you wondered whether a trip was a “colossal waste.” You mention “grasping at straws,” and a “series of extreme long shots.” Trip after trip, and archive after archive, led to a lot of dead ends. I found myself wondering: did you ever lose faith that you would find anything?

CT: I did, for sure. Here’s the thing: you’re right in saying it was dead end after dead end. But the other side of that was, each one of those dead ends taught me something new. Even if it was a tiny little new fact, often times it gave me some new insight, some new avenue that I thought I could follow up, that maybe then would hold out the hope of making a great discovery in the end. And so, even though stop after stop I didn’t find what I was looking for — and yes, that was extremely frustrating, because I wanted to find it, because I was spending time and money trying to find it, and because I had a publishing house waiting for this book that wanted me to find it, so there was a lot of stress and a lot of weight on my shoulders — I was always learning something new and potentially important.

Daniel Estrin is an American journalist in Jerusalem. He has reported on archaeology for The Associated Press, NPR and The New Republic.

Related Content: