Jonathan Kirsch, book editor of The Jewish Journal, contributes book reviews to the print and online editions and blogs at www.jewishjournal.com/twelvetwelve. His most recent book, The Short, Strange Life of Herschel Grynszpan: A Boy Avenger, a Nazi Diplomat, and a Murder in Paris, was published under the Liveright imprint of W. W. Norton to coincide with the 75th anniversary of Kristallnacht. He will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

Last month, shortly before the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, my wife, Ann, and I took a tour of Terezín, the fortress near Prague where more than 100,000 Jewish men, women and children were briefly held by the Germans and their accomplices in a transit camp before being sent on to the death factories and the killing fields.

Last month, shortly before the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, my wife, Ann, and I took a tour of Terezín, the fortress near Prague where more than 100,000 Jewish men, women and children were briefly held by the Germans and their accomplices in a transit camp before being sent on to the death factories and the killing fields.

Our local guide felt it appropriate to tell us that the Jews in their tens of thousands were guarded only by 22 SS men.

The guide was dead wrong. “[B]y the end of 1941, [Terezín] housed some 7,000 German soldiers and Czech civilians,” writes Saul Friedländer in The Years of Extermination, the second volume of his masterwork, Nazi Germany and the Jews. But the subtext of the guide’s remark is not different from the question that Israeli prosecutor Gideon Hausner asked the survivors who appeared as witnesses at the Eichmann trial: Why did you not fight back?

A good deal of Holocaust scholarship, in fact, has been devoted to showing that the Jews did fight back in greater numbers and more various ways than our guide at Terezín was willing to admit. Yehuda Bauer has adopted the word Amidah, a reference to the “standing prayer” that is the centerpiece of the synagogue service, to honor the Jews who “stood up” against the Germans and their collaborators, some with “cold” weapons like sticks and stones, some with “hot” weapons like guns and bombs, some by smuggling food and medicine, and some by teaching a few words of Hebrew to the children before their lives were taken from them.

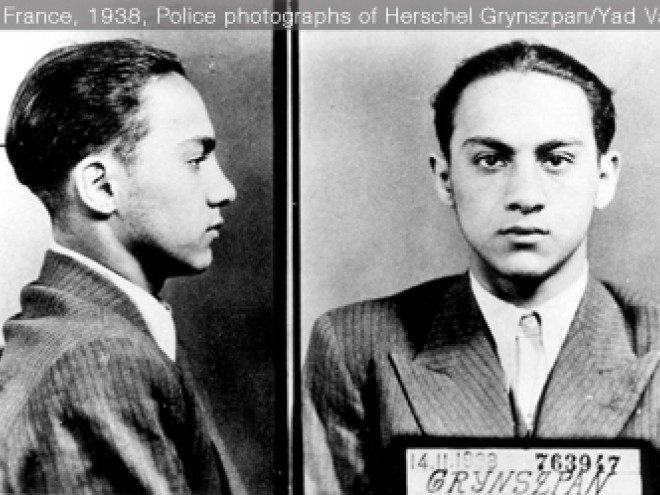

The question of Jewish resistance is sore point for me, too. When I set out to tell the story of Herschel Grynszpan, a 17-year-old boy who was among the earliest Jews to engage in an act of armed protest against Nazi Germany, I was both saddened and puzzled at the way he had been wholly written out of history, and as much by the Jewish community as by the rest of the world. At a time when the Jewish world was terrorized by the Nazis, Herschel sought to call the world’s attention to their plight, but he was shunned at the time and forgotten afterwards.

Why, then, is Herschel Grynszpan not celebrated as the hero he fully intended to be? “To bring the attention of the world to what was being done to the Jews was an act of resistance,” Prof. Friedländer told me in an interview. “Why Herschel Grynszpan has been overlooked, even if his act had unfortunate consequences, is strange and baffling.”

That’s precisely the question I sought to answer in my new book, The Short, Strange Life of Herschel Grynszpan: A Boy Avenger, a Nazi Diplomat and a Murder in Paris (Liveright). And it’s a question I will explore in my subsequent postings as a guest blogger for the Jewish Book Council.

As it turns out, I found a few clues to the mystery in Herschel’s scandalous life story, and I look forward to sharing them with you.

Jonathan Kirsch is author of 13 books, book editor of The Jewish Journal, and an intellectual property attorney in Los Angeles.