The Talmud tells the story of the time when King David sets out to dig the foundation of the Temple that would stand in Jerusalem. David digs and digs until he finds a little ceramic pot and reaches to pull it out. But this piece of pottery speaks and says to David, “Do not move me.” David asks, “Why not?” The pot replies, “I am here to hold back the tehom, the abyss” (Jerusalem Talmud, Sanhedrin 10:2).

The Book of Genesis introduces us to the idea of tehom in its first verses: “When God began to create the heavens and the earth, the earth was unformed and void. And there was darkness over the face of tehom—the chaotic abyss” (Gen. 1:1 – 2). In the story of creation, the tehom seems to be an essential, if disordered, ingredient of creation, part of the foundation upon which the world is built. However, just a few chapters after the creation of the world in Genesis, once Noah and his family are safely inside the ark, “The tehom bursts open and the earth is entirely overcome” (Gen. 7:11). In Noah’s story, chaos is a relentless, crushing wave that overtakes everything in its wake. Once it is released, there is nothing to hold it back. The same tehom that serves as the foundation of all creation also becomes the singular force for its destruction.

This is the force David encounters when digging the foundations of the Temple; just a simple shard of pottery lies between him and chaos: “I am here to hold back the tehom.”

But David lifts it anyway. And when he does, the tehom rises and threatens to flood the world. David can’t fit the pot back into its place. So what should he do? The Talmud tells us that he begins to sing:

A Song of Ascendings.

From the deepest place in me I called You, Adonai.

… For with You pardon dwells … (Psalm 130:1, 4).

David composes the ma’alot psalms, the songs of ascent. And as he sings each of these soaring psalms, the world is lifted from the tehom (Jerusalem Talmud, Sanhedrin 10:2). Pushing the darkness back down is not possible, so instead, David — with his music and poetry — lifts the world up. Legend has it that our most beautiful and enduring songs of hope were created in the face of overwhelming despair.

When I began my own exploration of the psalms as part of my rabbinic capstone project about eight years ago, I often felt myself in David’s place, trying to suppress the rising darkness, to stop it from seeping through the cracks. This is what led me to write To You I Call: Psalms Throughout Our Lives. There is so much tehom in the world around us; there are so many reasons to despair. I was searching for the words to simultaneously express the yearnings of my heart and to connect me with Jewish tradition. I was looking for a way to face the growing tehom, and for words of comfort to offer to others. I was looking for a way to do my small part to lift the world up. Just like David, I felt companionship amid hopelessness. The psalter provides us with the opportunity to deepen our connection to each other, to our ancestors, and to God, if only we know where to begin. That is what To You I Call strives to do: to pair ancient psalms with our contemporary needs, whether we are experiencing despair and pain (such as losing a loved one or facing antisemitism) or gratitude and healing (like coming out or celebrating a birthday).

Our tradition teaches us that years after David dug the Temple’s foundation, the construction was completed and these ma’alot psalms became the ones our ancestors recited as they ascended the Temple’s steps. And after they did so, they would enter the courtyard of the Temple, reciting verses of psalms the entire time. Then, the usual path around the courtyard would take them along a circle to the right. But a person who entered the courtyard in despair would circle instead in the opposite direction, to the left. The people circling to the right would look into the faces of the people circling to the left, and would ask: “Mah lach? What has happened to you?” After the person circling left answered, the person circling right would offer them a blessing (Mishnah Middot 2:2).

It was upon the Temple Mount, the place where David unleashed the tehom and where primordial darkness threatened to overwhelm everything, that our ancestors would look each other in the eyes and offer the simplest yet most profound acts of kindness: recognition, understanding, blessing. Relief was not necessarily possible, but companionship was.

There is much reason to despair today. In the past year alone, we have all entered that courtyard and, dare I say, turned left. We have all felt despair’s depths, lost loved ones, struggled with illness, felt the crashing of deeply held beliefs, the feeling that we cannot summon any more strength or fathom any more grief, any more pain. We have felt the shattering of hope itself, the threat of the rising tehom. So much has been lost, and it seems that there is still so much yet to lose.

We learn from our ancestors, who experienced times as dark as these, that we cannot force the chaotic abyss back beneath the earth; it was released long ago. What we can do is return to that courtyard. We have a community, a whole world even, singing beside us. We are all despairing. And because of it, we are not waiting or looking for hope — we are composing it. We are becoming it. We greet each other, shoulder to shoulder, we grasp hands, and step by step, we lift the world up. We are each other’s Songs of Ascent.

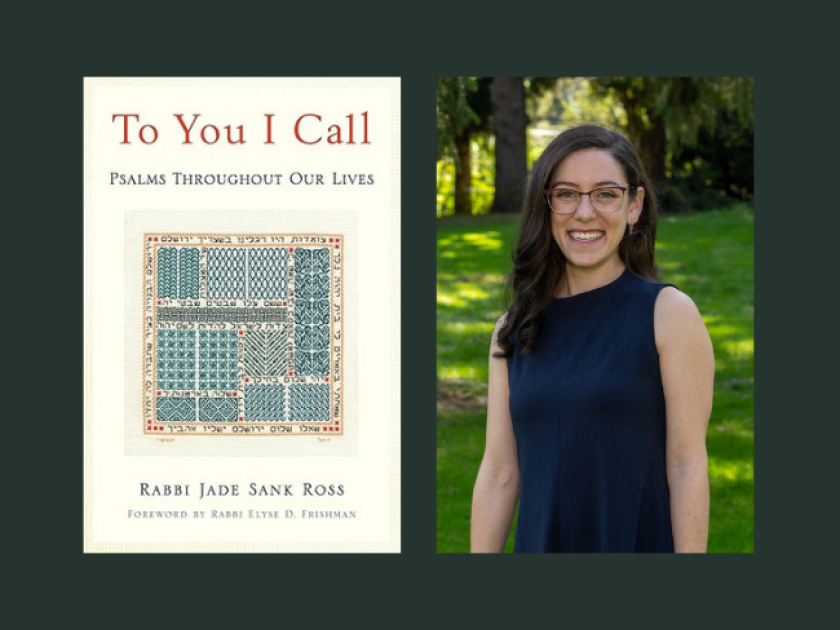

Rabbi Jade Sank Ross grew up in Kinnelon, New Jersey, where she spent the majority of her days divided between the local stables riding horses and her Jewish home, Barnert Temple, in Franklin Lakes, New Jersey. It was because of her involvement at Barnert Temple and because of the mentorship of Rabbi Elyse Frishman, Cantor Regina Lambert-Hayut, and Director of Lifelong Learning Sara Losch that Rabbi Sank Ross discovered her calling as a rabbi.

Rabbi Sank Ross received her BA in anthropology and international and global studies from Brandeis University, where she was also a member of the a cappella group Company B. She was ordained as a rabbi in 2018 by the Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion in New York, where she earned awards for her achievements in homiletics and human relations.