Mapping out a field is an ambitious, risky, and demanding endeavor. It is also a valuable achievement when it is carried out with the self-awareness, thoroughness, and verve that characterize Josh Lambert’s guide to American Jewish fiction. For each of the 125 entries arranged chronologically from 1867, Lambert provides just enough information about the plot, theme, style, history of publication, and suggested further readings to be both informative and evocative about each of the works. The author strikes a balance between canonical writers, such as Bellow, Ozick, and Roth, and lesser known writers who deserve attention, among them Delmore Schwartz, Jo Sinclar, Johanna Kaplan, and Raymond Federman. By employing theme rather than biography as his guiding principle, he includes significant works by non-Jewish authors such as Gish Jen, Henry Harland, and John Updike. The volume also includes useful appendices of untranslated Yiddish and Hebrew novels, anthologies, and bibliographic sources. Without the pretense of comprehensiveness, this guide is a pleasure to read, the result of Lambert’s wry and breezy style. Appendices, index.

The Chosen Books: What Makes a Book Jewish?

By Josh Lambert

Since you’re reading Jewish Book World, this is probably a question you’ve asked yourself, at least briefly, at one point or another. If you’re a librarian or bookstore owner, editor or reviewer, literary scholar, or book group leader, you may even have decided which books count as Jewish and which books don’t for a particular project, issue, display, or collection. I had to think about this all the time while writing my book, American Jewish Fiction: A JPS Guide, which explores the field through short reviews of 125 classic novels and short story collections published between 1867 and 2007. What books would I include, and which ones would I leave out?

Many of these decisions are easy enough to make. Everyone agrees that a book written in a Jewish language like Hebrew, Yiddish, or Ladino, can be counted as a Jewish book. Even when they have nothing to do with Jews or Judaism, it would be hard to deny that such books maintain some relation to Jewish writers and readers. Sure, the Yiddish translation of the New Testament was produced to help Christians convert Jews, but the book remains Jewish in a sense because of its language and its intended audience.

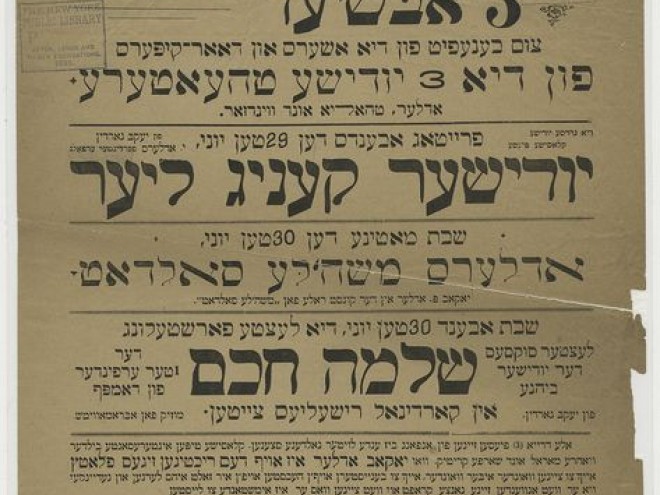

Since my focus was on American fiction, I could immediately and enthusiastically add to my list many novels written in Yiddish, including works by David Pinski, I. J. Singer, I. B. Singer, and Chaim Grade; my publishers requested that I steer clear of any books that have not been translated into English, which meant picking Isaac Raboy’s Der yiddisher kauboy (Jewish Cowboy, 1942), rather than his earlier and somewhat similar novel Herr Goldenbarg (1913), and leaving out books like David Ignatov’s In keslgrub (1918) that have not yet been translated. Sadly, this requirement meant excluding many novels and short story collections written in Hebrew about life in America by writers including Simon Halkin, Reuben Wallenrod, Razia Ben-Gurion, and Maya Arad (though I mention several of these in an appendix for those able to read them in the original). But I never had to think too deeply about whether these Yiddish and Hebrew books should be considered Jewish.

Even when dealing with non-Jewish languages— in the case of my own book, particularly with novels written in English — some decisions pose no great difficulty. Who would deny that Milton Steinberg’s As a Driven Leaf (1939), which dramatizes a set of stories from the Talmud, is a Jewish book simply because Steinberg, a congregational rabbi, chose to write it in English? The real complications begin with writers who were not rabbis and with stories drawn not from central and traditional Jewish texts, like the Talmud, but from modern experience in all of its ambiguity and dynamism.

A few borderline cases will help to demonstrate the problems that tend to crop up. Nathanael West (né Weinstein) wrote extraordinarily dark and resonant satires of American culture in which Jews do not figure as primary characters, and while J. D. Salinger was a rabbi’s grandson, his stories of alienated young geniuses and dysfunctional urban families, including Catcher in the Rye (1951), barely mention Jewishness. An even more resonant case is that of the famed Czech writer Franz Kafka, whose diaries and letters reveal an intense fascination with and attention to Jewish life and history, but who never mentions the word “Jew” or “Jewish” in a single one of his novels or stories.

To justify including works by these writers in the category of Jewish literature, critics often argue that their books subtly symbolize something fundamental about the modern Jewish experience, even if they don’t explicitly mention Jews. Saul Bellow, for example, characterized a Jewish book as one in which “laughter and trembling” are “curiously mixed,” and by this standard, West and Kafka would be shoo-ins, while Salinger would have a fair shot. Cynthia Ozick, meanwhile, has called for a “liturgical literature,” and depending on how one defines that purposely vague term, West, Salinger, and Kafka could all be in, or out. Ruth Wisse, professor of Jewish literature at Harvard, proposes that “in Jewish literature the authors or characters know and let the reader know that they are Jews,” under which criterion West, Salinger, and Kafka would all be summarily excluded; nevertheless, Wisse insists on including Kafka in her Modern Jewish Canon (2000), as she perceives “the permanent anxiety of a Jew writing in German” in The Trial (1925). Noting the long history of such disagreements and confusions, Hana Wirth-Nesher remarks, in an anthology of essays on this topic, titled What Is Jewish Literature? (1994), that “there is no consensus nor is it likely that there will ever be one.”

Why not say, then, as Michael Kramer, a professor of English literature at Bar Ilan University, does, that “Jewish literature is simply literature written by Jews”? Kramer means this literally and absolutely: he includes any books written by any Jew “regardless of any relationship to Judaism or yiddishkayt or any of the many versions of Jewishness that have strutted across the stage of modern Jewish history.” For Kramer, if it turns out that a Jewish person wrote PowerPoint for Dummies, well, then that’s a Jewish book.

For many readers, Kramer’s approach will seem needlessly broad — does he really imagine that the Jewish section at Barnes and Noble could include every book written by a Jewish author? And who exactly is supposed to check to see whether the author of The Bacon Cookbook had a bat mitzvah? — but even this inclusive approach is also not nearly broad enough. Plenty of books written by proud and unambiguously identified non-Jews surely deserve mention in any discussion of Jewish literature, from George Eliot’s influential proto-Zionist novel Daniel Deronda (1876) to the most recent winner of the National Jewish Book Award for fiction, Peter Manseau’s Songs for the Butchers Daughter (2008). Manseau’s book appeared too late for me to include it in American Jewish Fiction, but I did include works by non-Jewish authors including Henry Harland, Edward King, and John Updike. I particularly recommend Gish Jen’s Mona in the Promised Land (1996), which features a young Chinese-American convert to Judaism.

It seems to me, finally, that the way to answer the question about what makes a book Jewish is to decide why you think anyone should read such books. Are these books meant to bring Jews closer to God? To explain Jewish life to non-Jews? To educate, to entertain, to perplex, to enlighten? Personally, I hope Jewish books can do all of these things, and that helped me to make my choices. After consulting with experts, literary scholars, and many voracious readers, I eventually chose novels about religious and secular Jews, about the Holocaust and Israel, about conversion and intermarriage, about Jews who are proud to be Jewish and about Jews who aren’t exactly sure what being Jewish means. And, for the record, I included novels by West and Kafka, but not Salinger. I imagine that not everyone will agree with these choices. In fact, I hope they won’t. That’s why I created a companion website, www.AmericanJewishFiction.com, where readers can let me know what books and authors I neglected and help me to build a more complete list.

We may never be able to agree, as Wirth- Nesher suggests, on what exactly makes a book Jewish. But by staking out positions and arguing about them, we’ll develop richer and more complex ideas about our literature, and even, perhaps, about what “Jewish” means.