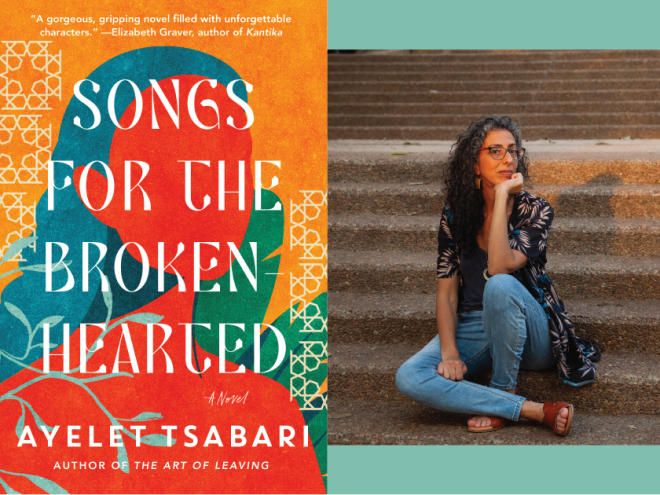

Ayelet Tsabari’s first two books, the short story collection The Best Place on Earth and the memoir The Art of Leaving, earned prestigious literary awards and attracted readers all around the world. Those readers will certainly welcome her first foray into the novel. Songs for the Brokenhearted is immersive, distinguished by sharp and agile prose, a remarkable cast of fully realized characters, and spellbinding storytelling. And when it comes to bearing witness to the vibrant history and culture of generations of Israel’s marginalized groups, the novel is an unparalleled triumph.

Tsabari elegantly weaves together two storylines, the first of which is set in the overcrowded squalor of an immigrant camp in the early years of Israeli statehood. The beginning of a great but forbidden love between two young people launches the narrative. Yaqub, an orphan from North Yemen, stumbles across a girl his age and is immediately smitten. Their poignant and intense attraction is just one of the many colorful threads forming this novel’s rich tapestry.

Set in the volatile summer of 1995, the second storyline is narrated by Zohara, who has been living in New York and struggling with a dissertation project she no longer finds inspiring. Zohara is a complex protagonist, at times mortified by what she thinks of as “primitive” aspects of her heritage, and at other times taking a perverse pleasure in self-exoticizing her identity among her American peers. While on vacation in Thailand, she learns of the sudden death of her mother in Israel. Returning to her mother’s house in a Yemini neighborhood in central Israel to mourn and clean, Zohara uncovers entrancing tapes of her mother’s singing (lyrics of which are delicately interwoven throughout the narrative) as well as artifacts testifying to a startling secret. Gradually, Zohara gains a deeper appreciation of the complexity and quiet heroism of her mother’s life, and the beauty, joys, and sorrows of a culture she has often resisted.

After living abroad, Zohara comes to recognize that as painfully deficient as Israel is, it is inextricable from her psyche. She recognizes both the individual and collective sources of her anger:

Israeli anger was a manifestation of helplessness, of grief. This was a nation of migrants, exiles and survivors, people who fled from genocide and persecution only to arrive at this place where wars never end … where border towns are shelled, buses explode, malls and cafes are blown up. A country erected on the ruins of others, the oppression of others. The conflict was everywhere; you couldn’t look away from it, and God knows, we tried. This was the reason we built an armor, constructed a bubble.”

And yet, despite everything, Zohara says that “this was the only home I knew. Flawed, imperfect, but home. And though my sense of belonging was fractured, still I belonged here more than anywhere else. Maybe that’s why I held on to this dream of peace so desperately. I needed to believe we were heading somewhere better.”

Zohara’s return also brings her closer to her sister Lizzie and her extended family, especially Yoni, a well-intentioned nephew who falls under the ominous influence of a far-right youth movement. Then there’s Nir, a Mizrahi grocery worker Zohara barely remembers from their school days, whom she gradually sees in a much different light. Through the shifting relationships between these and other memorable characters, Tsabari deftly explores the fluid nature of self-understanding and our understanding of others.

The murder of Yitzhak Rabin is not the only traumatic episode in Israel’s history addressed in this emotionally intense novel; Tsabari also chronicles the still barely recognized kidnapping of Jewish Yemenite babies by the Ashkenazi establishment. As intricate as all this sounds, the novel never once loses its footing. Tsabari masterfully foregrounds the social upheavals of two transformative historical eras, illuminating intergenerational schisms and healing in unexpected ways. And to Tsabari’s credit, she portrays Zohara, who often seems like the author’s own surrogate, as a likable but sometimes obtuse young woman. We witness both her virtues and flaws as she gradually awakens to the joys and wisdom of the Yemeni oral poetry of her mother’s generation and all it represents:

“How many of us really know our parents? Especially women. They didn’t want to be known. They were taught to be quiet, to take no space. They believed their stories had no value. I used to ask Ima about her life, and she kept saying, ‘There’s nothing to tell.’”

By this point, Zohara and the reader have reason to know better.

Like the protagonist of Songs for the Brokenhearted, Tsabari was born in Israel to a family of Yemeni background and has worked and traveled extensively outside of Israel. Here, she employs her insider – outsider perspective in ways that are psychologically astute and culturally sophisticated. This soaring novel does justice to it all: the feverish highs and lows of love affairs, personal and collective forms of grief, tempestuous family dramas, issues of gender and belonging, and Israel’s divisive politics. Like Zohara’s mother herself, it sings.

Ranen Omer-Sherman is the JHFE Endowed Chair in Judaic Studies at the University of Louisville, author of several books and editor of Amos Oz: The Legacy of a Writer in Israel and Beyond.