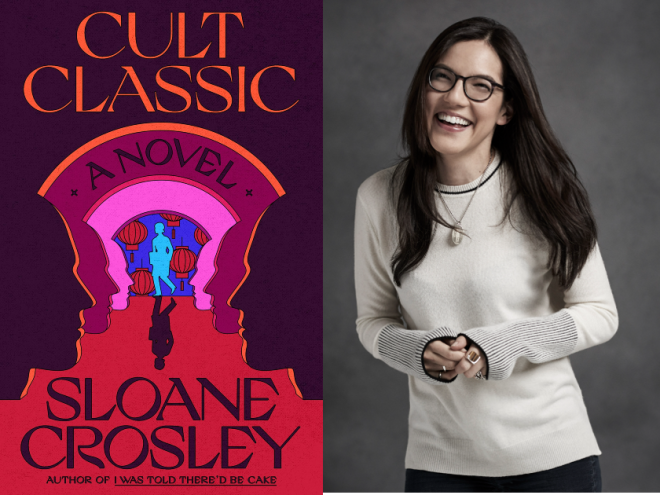

In Sloane Crosley’s novel Cult Classic, Lola is thirty-seven and a mid-level editor at the website Radio New York. She lives with her fiancé, nicknamed “Boots,” but is lukewarm on the relationship. One night, she runs into an old boyfriend outside a fusion restaurant, gets a drink with him, and feels the tug of her past. After a second chance encounter with a different ex, she starts to feel that something bigger than herself is happening — and it is. Lola has been chosen for an experiment by the Golconda, an organization founded by her former boss Clive. Lola calls it a cult, Clive calls it a “movement”, and its first task is to “fix” Lola’s love life by having her confront past boyfriends and move forward in her relationship with Boots — before, in so many words, she wrecks it. As her best friend notes, it’s “like a romantic Minority Report.” Lola is skeptical but game.

The Golconda’s headquarters is a disused synagogue on the Lower East Side, which is an interesting detail since, as Lola points out, Clive is not even Jewish. In one sense, it could simply be an ironic nugget of storytelling, highlighting that urban thirty-somethings are so detached from religion that the origins of the Golconda don’t even matter; despite this, Lola, who is herself Jewish, starts to feel a sense of connection there — at one point she runs toward it “as if it were an embassy on foreign soil.” The writing also indicates that the physical space of the synagogue is imbued with spirituality, even if it takes Lola a long time to feel it — it is a temple, “a place where people had come to learn and recite and be reprimanded by God’s law.”

In revisiting her old relationships, Lola realizes that she has reframed every breakup narrative to give herself more agency. Counterintuitively, she seems fed up with her own agency and wishes she could be “put on the shelf like a cake platter and think of nothing.” To a certain extent, she is the kind of mixed-up millennial woman seen before in novels such as My Year of Rest and Relaxation and Fake Accounts. But Crosley (perhaps best-known for her collection of essays I Was Told There’d Be Cake) is an especially funny writer, and she injects that humor into Lola’s sharp-eyed metaphors as our narrator (“I could feel Death, stringing cobwebs along the walls of my uterus like Christmas garlands”).

In light of that, the minor “flattening” of Lola’s personality that accompanies the resolution at the end of the novel seems a little sad at first glance. But in a darkly comedic reminiscence Lola has with Clive at the tail end, Crosley seems instead to suggest that the ending we see is just one possible way forward out of many.