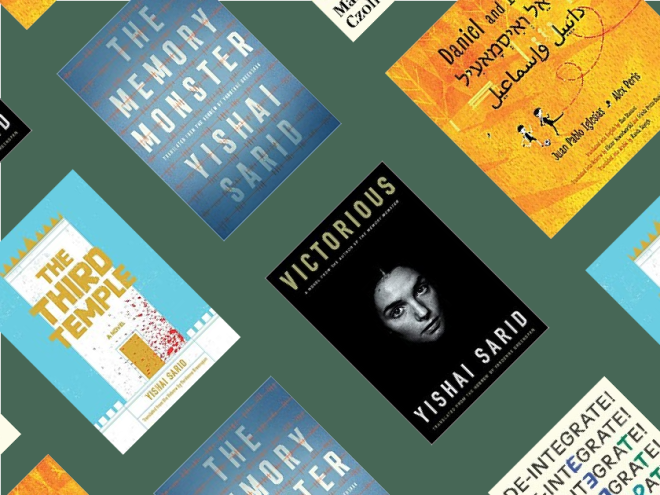

Daniel and Ismail is an unusual and ambitious offering from the non-profit publishing house, Restless Books. The illustrated story follows the friendship of Daniel, a young Jewish boy, and his Palestinian friend, Ismail. Both love playing soccer and each is part of a culture deeply entrenched in both its own traditions and its own prejudices, over which the boys have no control. The book has been translated from Juan Pablo Iglesias’s Spanish into English, Hebrew, and Arabic; each page features text in all three languages. The book does not attempt to explain the Israeli-Palestinian conflict nor does it justify, or even contextualize, each side’s grievances. Instead, author and illustrator present an alternative fable, one where the joy of friendship and the comforting dreams of their interior lives allows Daniel and Ismail to ignore the hatred which threatens them. Stavans previously wrote an essay on the process of translating the book and its inception.

The book is set in Chile, home to a large Palestinian population and a smaller Jewish one. Daniel and Ismail live in an unnamed city and were born on the same day. A chance encounter in a public space leads to an improvised game with a soccer ball. The author’s minimal background information about his protagonists’ lives makes it clear that this is not a work of realistic fiction and is not intended to trace the historical routes which cause an innocent mistake to become a dangerous moment. Both Daniel and Ismail have received special birthday gifts charged with the weight of their identities as a Jew and a Palestinian. Daniel brings his tallit and Ismail his keffiyeh to the park, where they lose track of time in the grace of unstructured play, “One of the balls almost reaches the sun. The other one floats on a cloud.” The author alludes to competition but not conflict, as the boys try to outdo one another in athletic feats. When they realize that they will be late returning home, reality returns and they rush to leave, inadvertently exchanging their gifts. They are abruptly transformed from children kicking a soccer ball into targets of anger. Pictures show their parents pointing and shouting at them; these adults are only depicted from the neck downwards, making them generic symbols of adult fury.

At this point in the story, the author implies that the boys have been aware of the violence in the Middle East, since they each have vivid nightmares about “what they have seen on the news” and “what they have heard adults say.” Children may need explanations of a reality not previously introduced in the book. Another focus of discussion may be the parallel use of a tallit, which is a Jewish ritual object, with a keffiyah, a traditional head covering which has acquired the meaning of national aspirations for Palestinians. The objects are clearly meant to be a kind of shorthand for Jewish and Palestinian identity but, at the same time, they are real things. In particular, Jewish children who are at all familiar with the purpose of a tallit might question why Daniel receives it as a birthday gift and why he brings it outdoors.

The book’s ending is reassuring, although not without a touch of sadness. Jewish and Palestinian children play together, both on the field and in their dreams of the future. There is no mention of the adults who reacted with horror at the spontaneous companionship of two boys with a soccer ball on a beautiful day.

Daniel and Ismail is highly recommended for children and will also be of interest to adults who are hopeful about the future.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.