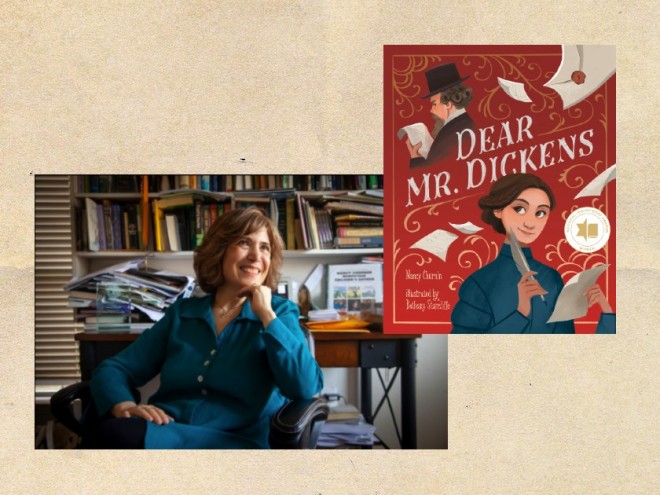

Readers today are well aware of age-old controversies surrounding insensitive portrayals of racial or ethnic groups in books. In Dear Mr. Dickens, Nancy Churnin and Bethany Stancliffe tell the story of one Jewish reader, Eliza Davis, who was a fan of novelist Charles Dickens but not of his antisemitic caricature in Oliver Twist. Davis felt that the character of Fagin represented a dangerously misleading portrayal of her people, so she wrote to Dickens in hopes of a response. The small drama of this interaction between a famous author and a woman seeking change makes for an inspiring story.

Many children might not be familiar with Dickens, but Churnin introduces the basic facts of his career with sensitivity and accuracy. He is “the most famous writer of Eliza’s time,” and readers eagerly await installments of his stories in popular magazines. Selective facts about the era and about Dickens’ work, including his commitment to exposing social evils, set the stage for Eliza’s decision. The implicit hypocrisy of the novelist’s compassion for Oliver Twist, a poor orphan, angers Davis; young readers will easily understand the idea that adults may fail to live up to their own ideals. Churnin carefully explains the difference between a character and a stereotype through Davis’s reasoning. Fagin is repeatedly identified as “the Jew,”suggesting that his horrible traits are endemic to the Jewish people.

Part of Eliza Davis’s appeal lies in her persistence. When her favorite author sends a defensive reply to her letter, she refuses to give up. Her second letter provides a lesson in both courage and calm reasoning and also includes more historical information about British history and literature. Davis brings up Dickens’s own Ebenezer Scrooge, as well as Rebecca of York from Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe. Churnin mixes specific period details with broader issues of personal courage and Jewish identity to create a meaningful narrative.

Stancliffe’s pictures represent nineteenth-century England as both distant and familiar. The expressions on characters’ faces reflect the universal nature of their feelings. Davis is angry and frustrated, and later she is filled with gratitude at Dickens’s ability to change. Her young son appears in many scenes, reaching up to place her letter in a mailbox and reading a book while his mother reads her letter.

Dickens himself is both an icon and a real person, resentful of Davis’s accusations as he sternly reads her first letter, but he is ultimately motivated to change. Stancliffe shows him actively involved in revising and reprinting a new version of Oliver Twist. The illustrations feature jewel-toned colors, with black-and-white inset pictures from Dickens’s works and other books providing contrast. Literature and life are indivisible in this story of an author and his reader, proving that words matter, especially when they are part of a dialogue.

This highly recommended picture book includes an author’s note, with further historical information.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.