Israel Baline began his career as a newsboy busking on the streets of the Lower East Side for pennies, sometimes slipping into a saloon and ad libbing salty lyrics to the sentimental ballads of the day. But with the publication of the groundbreaking “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” Izzy Baline — now Irving Berlin — was, at twenty-three, an international celebrity. In his brisk and thoroughly enjoyable biography of Berlin, James Kaplan charts this remarkable rise and Berlin’s century-long life.

The youngest of eight children of an immigrant family, Berlin dropped out of school when he was thirteen and left home to make a living. With his sweet voice and steely determination, he ultimately landed a job as a singing waiter and officially became a songwriter at twenty-one, when he was hired as a staff lyricist at Waterson and Snyder. His first song for the publisher earned him $3,000. With the smashing success of “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” the publishing company became Waterson-Berlin-Snyder.

The genius of Berlin’s songwriting was his uncanny ability to create melodies that perfectly matched his lyrics. He stressed simplicity of words and music, and it was sometimes said that he created songs almost on the spot, but with the exception of “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” — reputedly written in eighteen minutes — Kaplan, a noted journalist, biographer, and novelist, confirms that the songs were the result of hours of agonizing work. Kaplan’s sharp analysis of Berlin’s lyrics reveals their deceptive simplicity, underlying sophistication and Berlin’s ear for the right word or melody in the right place.

When drafted during World War I, Berlin turned his distaste for army life into “Oh How IHate to Get Up in the Morning” and ultimately Yip! Yip! Yaphank, a revue created as a fundraiser for the army. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Berlin wrote to General George Marshall suggesting an updated version. This Is the Army drew packed houses for three months and then went on a cross-country tour, earning millions for the army. Berlin then took the show on the road, first to the British Isles and then, for the next two and a half years, to the front in North Africa, Italy, and the Pacific. A notable feature of the show was that it included, at Berlin’s insistence, two dozen black soldiers, making it the only integrated unit in the U.S. Army.

A noted celebrity and immensely successful both professionally and financially, Berlin nevertheless suffered from bouts of self-doubt and periods of depression. A bundle of nervous energy, he was a compulsive worker, an insomniac who often worked through the night. His life was unexpectedly overturned when his wife died five months after their marriage, leaving Berlin a widower at twenty-three. He remarried fifteen years later, an improbable but deeply loving match with a Catholic heiress fifteen years his junior that lasted more than sixty years.

One of the pleasures of Irving Berlin is Kaplan’s lively and affectionate overview of the New York musical scene in the first half of the twentieth century. Kaplan takes the reader on an inside tour of Tin Pan Alley and the Broadway stage, with, like Berlin himself, dashes to Hollywood. One of the masters of the American Songbook, Berlin wrote more than fifteen hundred tunes, and as Kaplan cites one after another of his hits, the great flourishing of the American musical stage from 1920 to 1950 comes alive.

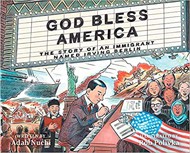

Perhaps the most telling mark of Irving Berlin’s genius was his ability, in his words, to “embod[y] the feelings of the mob.” A Jewish immigrant from Belarus, he caught the heart of Christian America in “White Christmas,” “Easter Parade,” and, most notably, “God Bless America,” a sincere expression of Berlin’s patriotism and love of the country. That these songs — along with so many more — are standards is a tribute to Berlin’s achievement and lasting impact on American popular music.

Maron L. Waxman, retired editorial director, special projects, at the American Museum of Natural History, was also an editorial director at HarperCollins and Book-of-the-Month Club.