Maira Kalman’s My Favorite Things is a book of wonders. Designed in three discrete sections, the author guides us through personal, historical, and imaginary collections of images, objects, memories, and words. Much of what she presents to us seems useless, inconvenient: a broken chair; a medallion; postcards from the Hotel Celeste in Tunisia; ticket stubs — “There is no reason,” our narrator declares, “to save tickets and stubs. They are tiny and inconsequential.”

Why, then, does she collect and display these things?

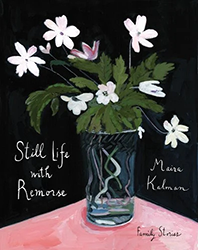

In the book’s introduction, Kalman writes of being asked to curate an exhibit based on the collection of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum. The project inspires her, and the second section of the book is focused on drawings and photographs of objects from that collection. Sometimes she carefully walks us through images of those objects: she presents us with a bed to sleep on, and then shoes to walk in upon rising from that bed, and finally some utensils to satisfy hunger after that long walk. These quotidian objects are infused with our collector’s delightful energy, in the form of colorful brushstrokes and often sparse, matter-of-fact declarations delivered in her whimsical and familiar handwriting. There are digressions and diversions, like the wide, rectangular drawing of a candy store window bursting with beautiful green and yellow and orange and red and brown boxes and chocolates and candies and tissues lining its shelves.

While the Cooper-Hewitt collection clearly inspired the author, the book contains much more than that particular selection of things. It opens with moments from Kalman’s personal history— a wedding photograph of her mother and aunt; a drawing of a room where her aunt used to give her “advice about life”; a photograph of Joseph Beuys’s suit. “Everything is part of everything,” Kalman writes at the conclusion of the book, having tied these personal memories to a museum collection to her personal collections to memories of events that occurred long before she was born. The book is suffused with sadness — “you can rely on sadness,” she explains— and these bathtubs and buttons and lists and doors and boxes recall moments that we, as readers, somehow become nostalgic for, alongside our narrator. “Objects inhabit the memories,” the author wisely tells us, and it is true, even if they were not initially our objects or memories; magically, they haunt us. The wonder is that they have been carefully considered, studied, drawn, and looked at. The wonder is that they were saved and collected at all.

Related content:

- Eight Nights of Snicket

- Jewish Artists reading list

- Essays on Illustration, Comics, and the Arts