When the Nazis began to deport the Jews of Bratislava, Slovakia in 1943, young Renee Hartman (her later married name) was forced into an unusual position. Not only did her parents, her younger sister, Herta, and she confront imminent danger, but Renee was the sole person in her family who was not deaf. Throughout the war, she took on the terrible responsibility of communicating crucial information to everyone in her home using sign language. After being separated from her parents, who did not survive, Renee tried to protect both herself and Herta, even throughout their imprisonment in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. In Signs of Survival, each sister remembers her own experience of this ordeal and each reflects on the lifelong process of attempting to grasp the incomprehensible in the context of each individual victim and survivor.

The book is an edited transcript of video testimony from the Fortunoff Video Archive at Yale University, and its tone is conversational and understated. At the same time that Renee and Herta relate their memories of trauma, they offer brief observations on the ultimate meaning of human suffering as well as indifference. While readers may have previously encountered the way that Nazi assaults on Jews represented the perverse opposite of Jewish values, it will have special impact for them to learn this truth through Renee’s words: “What made it worse was that the Nazis abused the very people to whom the Jewish religion says you should show the greatest kindness, namely, the old, the sick, and the young.” Herta’s quiet tone in reporting the last time she ever saw her father is heartbreaking because it captures the unaffected nature of a child: “I have always regretted that I was sleepy and didn’t hug him back.” Although Renee had taken on a parental role toward her sister, at one point this dynamic was reversed. After falling ill with typhoid, which was endemic in the camp, Renee lost the will to live, while Herta repeatedly implored her to “be strong.”

After the sisters were freed from Bergen-Belsen by the British military, they were sent to a center for refugees in Sweden. Herta, whose disability had limited her access to an education, was able to enroll in a school for the deaf in Stockholm. Although this opportunity separated her from her sister, Herta was “thrilled” to be able to be in a supportive environment with other deaf children. Later, after Renee and Herta join their American relatives in New York City, she continues her education at the Lexington School for the Deaf. Few books about the Holocaust focus specifically on Jews with disabilities who were far less likely to survive since they were almost always targeted for immediate murder. Herta’s unusual status makes it even more poignant when she is forced to end her studies in order to find a job. Her stoic attitude may mask deep disappointment: “So, unfortunately, I obtained only a few years of education as a young person, but somehow I managed well.” After being married and widowed, she raised three children, all of them deaf.

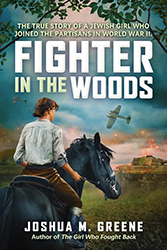

This highly recommended book includes an “Epilogue,” by Joshua M. Greene in which he argues that factual accounts of the Holocaust are incomplete without the direct testimony of survivors, such as those archived at Yale. This book certainly supports that assertion. Yet it would also be helpful, when sharing it with children, to provide supporting background materials. While many books which focus on oral histories integrate these personal stories into a broader framework, Signs of Survival, as Greene points out, is an edited transcript of interviews. There are some errors, such as Renee’s introductory comments about her background in which she states that Bratislava, where her family lived, was the capital of Czechoslovakia. (It became the capital of the Slovak puppet state under Nazi rule.) When she alludes to medical experiments on prisoners in Bergen-Belsen, it would be important to provide documentation about the numerous camps where such atrocities took place: Auschwitz, Dachau, Buchenwald, and others. There may well have been cases in other camps such as Bergen-Belsen but students will benefit from access to a more complete picture. Finally, it is unclear why this moving and essential account of two courageous women’s lives is credited only to Renee Hartman and Joshua M. Greene, when a significant part of the text is composed of Herta Rothenberg Myers’s contributions.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.