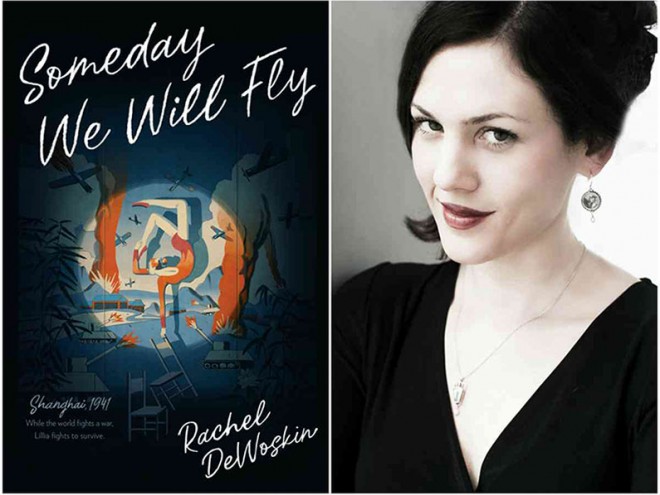

Lillia Kazka and her family are circus performers in pre-World War II Poland, where the dangers faced by the Jewish members of their company are staged ones. Risks are dramatic and exaggerated, participants and audience members understanding that escape from peril will be the entertaining outcome. Mothers protect their tightrope-walking daughters by reciting tehillim (psalms), and “No one minded Jewishness yet.” In Rachel DeWoskin’s deep and harrowing novel, her characters lives are more than just metaphors for the precariousness of Jewish existence. This is an exploration of Jewish refugees who found shelter, of a kind, in Shanghai during the War. The sense of life as a chaotic performance, its actors robbed of autonomy, may seem an obvious structure to impose on this time in history. Yet DeWoskin’s philosophically searching narrative completely avoids simple parallels or comforting redemption. Someday We Will Fly is a brilliantly realized human drama, its threatened protagonists responding to their imprisoned lives with both desperate contortions and unbelievable grace. Vast human suffering, as well as the particulars of Jewish historical suffering, define this novel.

Lillia’s world has been a paradox, defined by a stable and protective family whose acrobatic career would seem to preclude the security that embraces her. As one reviewer described the skillful illusions of her parents, her mother, Alenka, is “weightless,” while Bercik, her father, is “a masterful anchor.” When her mother disappears, a victim of Nazi terror, her weightlessness becomes literal, as Lilia’s longing for a missing parent hovers over her consciousness. Her father, meanwhile, manages to orchestrate the escape of the rest of their family. As the strains of caring for Lillia and her disabled baby sister gradually weaken him physically and emotionally, Lillia responds to their family’s disintegration with solutions which erode her dignity. Her exchanges with her father and her own internal monologues question the stability of human identity. Has “Warsaw Lillia” wholly disappeared, replaced by the compromised victim which she has become? As Lillia states with more anger than resignation, “I was tired of other people’s facts.” Even God is not immune to her accusations; aboard ship to China, she pictures Him “moving us around the decks like dolls…organizing as I used to when I had a dollhouse.”

There are many secondary characters who interact with Lillia, all of whom share this terrifying lack of agency. Other Jewish women become mother figures to her, only to suffer the same fragile fate as her own mother. At the Kadoorie School for Jewish refugees, Lillia confronts the social and economic hierarchies which divide their community, and which prove to be as impermanent as everything else after the attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into the War. Girls who where safe and privileged change place with those living under the worst circumstances. Although relationships between Jews and the native Chinese are limited, Lillia’s deep attachment to a Chinese boy, Wei, is utterly convincing and entirely free of exoticism. DeWoskin often conveys the intensity of Lillia’s experiences through a mixed sense impressions, as when she feels her Warsaw synagogue to be “warm with syllables.”

The book concludes with a detailed list of historical sources, and an “Author’s Note” of great importance. DeWoskin explains the difference between works of history and historical fiction, and admits, without apology, that some relationships in the book would have been less probable than others. Most importantly she reminds us that authors “have to do our homework,” and that she spent years consulting countless documents. Mere identity as a group’s member does not grant automatic access to the complexity of that group’s past. Nor does being a curious, gifted, and empathic member of a different group deny an author the possibility of understanding that past. As much as Someday We Will Fly is a work of Holocaust fiction, it is also DeWoskin’s meditation on the nature of historical fiction itself: “Historical fiction allows writers and readers to visit moments that aren’t the ones we live in, and to create connections between then and now.”

Someday We Will Fly is highly recommended for readers from fourteen to adult.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.