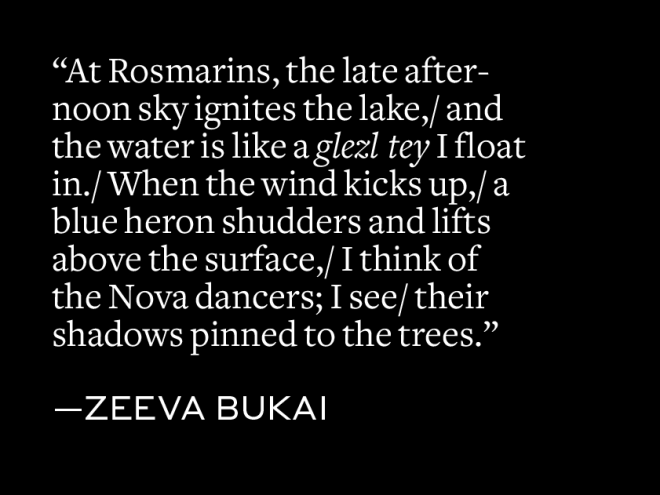

In her tremendous, transporting debut, The Anatomy of Exile, Zeeva Bukai demonstrates the unique power of literature to transcend borders, excavate our shared humanity, and perhaps even heal.

The novel begins in the aftermath of the Six-Day War, when Ashkenazi sabra Tamar Abadi learns that her Mizrahi sister-in-law, Hadas, has been killed. The presumed terrorist attack turns out to be a tragic, final act of passion in a decades-old secret love affair between Hadas and a Palestinian poet. He once inhabited her home in Kafr Ma’an — an Arab village displaced by the Israeli government in 1948 and then resettled by Mizrahi Jews — which she had lived in as a teenager. Hadas and her older brother, Salim, had been new immigrants in exile from Syria.

Upon hearing the news, Salim weeps, “the sound like a landslide, like trees torn out by their roots, like houses crumbling to the ground,” then abruptly uproots Tamar and their three children to live in America, as if that might erase his grief. Of course, Brooklyn isn’t exactly the Eden of his dreams. Years pass; pain persists; economic mobility is slow-going.

History repeats itself when their eldest daughter, Ruby, falls in love with their Palestinian neighbor, Faisal Mamoudi, who is originally from Jaffa. Triggered by memories of her sister-in-law’s devastating end, Tamar tries to protect her daughter from a similar fate, but her hardened prejudices only further strain the very relationships she hopes to preserve. In many ways, the Mamoudis understand Salim — a fellow Arab — better than his Ashkenazi wife does. In a marriage and family frayed by bigotry, betrayal, and chauvinism, Tamar feels increasingly unmoored in America. When the Yom Kippur War breaks out in 1973, she makes a return to Israel, whereupon she finally seizes the opportunity to rectify her past biases and stand up for justice in the name of empathy, peace, and love.

This is a vital exploration of what it means to be in exile, and how the loss of an anchor necessitates a reckoning with the self — a self without borders, without country, without land. Bukai writes with lyrical urgency and compassionate insight about identity, belonging, dispossession, and desire, capturing the doomed irony of homeland and the lengths to which people will go to insulate themselves in a false notion of safety. Her characters are flawed, contradictory, and haunted by warring desires. Amid our current backdrop of polarization and snap judgments, Bukai’s novel is a beautiful antidote, reminding us that nuanced stories are more necessary than ever. We cannot hear it enough: “People matter, ima, not states, not borders. Real people.”

Sara Lippmann is the author of the novel Lech and the story collections Doll Palace and Jerks. She is co-editor of Smashing the Tablets: Radical Retellings of the Hebrew Bible and co-founder of the Writing Co-lab, an online teaching cooperative based in Brooklyn. Her new novel, Hidden River, will be published in 2026.