On March 28, 1944, while Dutch minister Gerrit Bolkestein was in exile, he spoke to the people of the Netherlands from London: “History cannot be written on the basis of official decisions and documents alone. If our descendants are to understand fully what we as a nation have had to endure and overcome during these years, then what we really need are ordinary documents — a diary, letters.

Among Bolkestein’s listeners — huddled around illegal radios across the occupied Netherlands — was the young Anne Frank. But she was not the only one to take this advice and write her experience down: in the weeks following the country’s liberation by Allied forces in May 1945, a campaign to solicit submissions from people across the small country yielded more than two thousand accounts of life under Nazi occupation between May 1940 and May 1945. Now housed in the archives of the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation (NIOD) in Amsterdam, these diaries, letters, and other writings and artifacts document a spectrum of experiences shaped by the various backgrounds, perspectives, and situations of the individuals who recorded them.

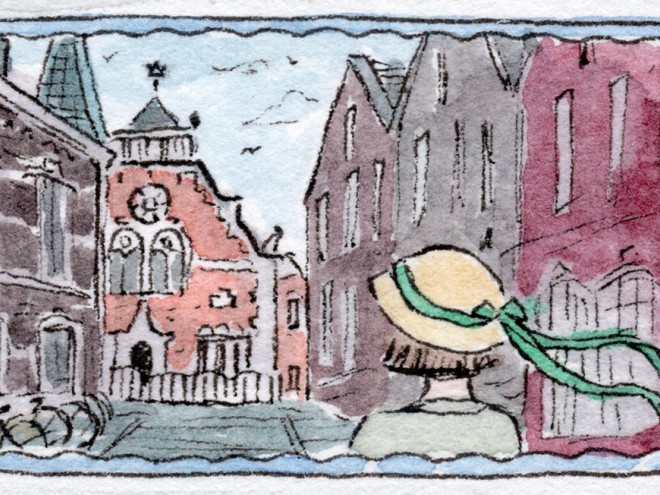

A journalist and researcher who has lived in Amsterdam for more than ten years, Nina Siegal was drawn to the Jewish history of her adopted city where, despite its monuments to its Jewish past, Jewish life today is difficult to find. She immediately recognized the importance of the NIOD diaries to fill in the gaps in the public memory, diving straight into this trove of first-person accounts of the war.

In The Diary Keepers, Siegal deftly weaves together the voices of a handful of those who, like Anne Frank, were inspired to record their everyday experiences under the Nazi occupation. Her selection highlights the Jewish perspectives of a journalist, a diamond cutter, and a secretary for a Jewish organization. Yet her work also accounts for a member of the Dutch resistance who saved many Jewish lives, a young factory worker, and Dutch supporters of the Nazi regime, including a policeman and a socialite married to a member of the Dutch SS.

Siegal allows her cast to tell their story chronologically, interspersing the excerpts with historical and personal references that provide richer context. The various commentators paint a narrative tapestry of events that illustrates the collective Dutch experience during the war and, at the same time, underscores the starkly individual realities of each experience.

This approach is insightful and revealing, but, as Siegal rightly cautions, the reader should be aware that the writers’ accounts may not be authentic. Diarists often adopt a persona that diverges from their own voice. This is especially true when they intend to share their commentary with others, as was Bolkestein’s intention when he called on the Dutch to record their experiences.

Ultimately, The Diary Keepers is a fascinating read and a valuable tool for understanding how “ordinary” Dutch people navigated the extraordinary circumstances of life under Nazi occupation — all without the benefit of historical hindsight.

Ingrid Weyher is the Program Manager for the University of Denver’s Center for Judaic Studies. She holds an M.A. in art history and history and specializes in Holocaust education.