Most readers will not be familiar with the life of Jella Lepman, the pioneer advocate for children’s literacy who founded the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY). A Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, Lepman returned to her homeland in 1945, committed to making books accessible to German children. She viewed this task as essential to preventing future wars. The Lady with the Books is not a biography, but rather a fictionalized hybrid. The basic facts of Lepman’s career are reflected through the characters of Anneliese and Peter, two German children for whom Lepman’s books bring a welcome respite after the destruction of the war years.

Lepman chose to distance herself from her Jewish identity, focusing exclusively on bettering the lives of German children; many Jewish organizations, working as she did, with the United States Army of Occupation, devoted themselves to helping the thousands of surviving Jews living in displaced persons camps. Stinson omits discussion of Lepman’s ethnicity in her story, although she does clearly identify Lepman as Jewish in the book’s backmatter. This beautifully illustrated tale conveys an important universal message of how books can make a difference in children’s lives.

Lafrance’s pictures show Germans clearing rubble and experiencing material deprivation. Anneliese and her mother stand in their kitchen; her mother gently holds a large teapot while Anneliese dries a plate. A limited color palette of only blue and brown gives a dream-like sense to the scene. Yet when the author remarks that the teapot “had survived the bombing with just one dent,” young readers will have no way of knowing that the bombing was part of the Allies’ defeat of the Nazi regime. The author is aware of this contradiction by creating a backstory about Anneliese and Peter’s family, in which their father had died while resisting the Nazis. While this would have made them an anomaly within the German population, it does provide an opportunity for readers to identify with sympathetic characters. When Lepman reads the classic picture book The Story of Ferdinand to a group of children, Peter associates Ferdinand the bull’s pacifism with his own experience.

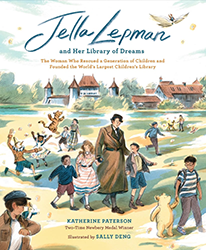

The book exhibition which Lepman organized eventually became a permanent affair known as the “Book Castle” in Munich, housing a world-class collection and reference library of children’s literature. When Anneliese and Peter visit the hall of books, they are overwhelmed by the riches they find there. Lepman is depicted as a kind and elegant older woman, while the books in the background are deliberately generic, with stylized lettering which does not correspond to any actual alphabet. When the children return home, even their bedtime stories and dreams are filled with fantasies derived from their visits to the book hall.

In reading this book with children, caregivers and educators, especially those in a Jewish setting, will want to raise questions about history and fiction, and to introduce age appropriate information about World War II and the heroic efforts to return Jewish books and ritual objects to their communities. In a detailed afterword, Stinson describes Lepman’s legacy of advocacy for children and the power of books to effect change. She writes that Lepman “was given the job of helping German children whose lives had been so badly disrupted.” Stinson and Lafrance’s book is a reminder that Anneliese and Peter are also victims of Nazism, and their story can be the beginning of a valuable conversation.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.