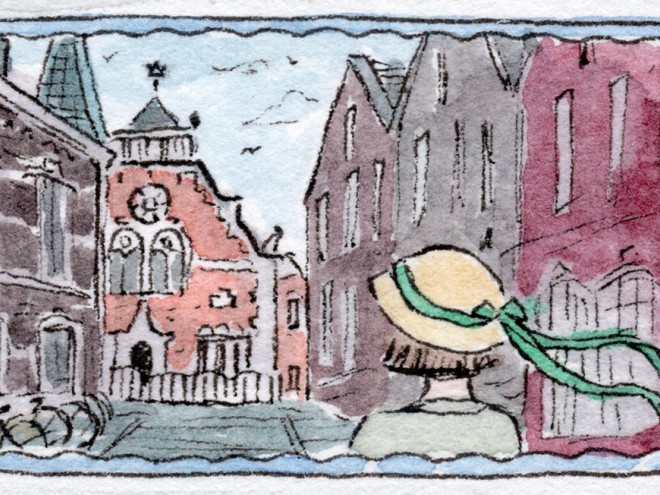

Set in the Netherlands in 1961, The Safekeep opens with the protagonist, Isabel, trying to convince her brother, Hendrik, that Neelke the maid might be stealing. Isabel lives alone in the family house. Their mother has died, and the house, owned by their uncle, is intended for Louis, the oldest brother, when he marries. The opening chapters convey the cultural and social limitations Isabel faces as a single woman, constraints that might explain her suspicions about Neelke and her overall churlishness. When Louis brings his girlfriend, Eva, to a dinner of the siblings, Isabel’s animosity toward the young woman emerges full-throated — but this does not stop Louis from bring Eva to the family home a few days later, with instructions for Isabel to host her while he is out of town for work. Isabel and the family home become a safekeep for Eva.

During their shared lodging, Isabel and Eva grow close and develop an amorous or at least sexual relationship. The Safekeep is a tightly plotted novel. In the first half, Yael van der Wouden adheres to the tropes of lust and sexual intimacy between women in the early 1960s. The Safekeep has the atmospherics of midcentury lesbian pulp novels, like Isabel Miller’s Patience and Sarah (1969). Van der Wouden creates a dark, unspoken, agitated world for Isabel and Eva, then pairs it with a plot that is deft and propulsive. By the end, lesbianism is hardly the biggest revelation.

The time period of the book — sixteen years after the end of World War II — reveals that the characters in the Netherlands have all continued to live inside the aftermath of the war and the knowledge it has brought. The Safekeep thus asks big questions: What is ownership? What does it mean to own objects, plates, silverware, chairs, beds, a home? How is ownership achieved — and, just as importantly, how is it lost? Who is responsible for these losses? How are individuals and their actions implicated in geopolitics?

These knotty moral questions, combined with a tightly wound plot, make The Safekeep an engrossing read. Van der Wouden’s meditation on ownership, responsibility, retribution, and reparations may resonate with Jewish readers of 2024. And recalling the atrocities of the Shoah and its many aftermaths feels urgent in light of rising antisemitism in the United States.

Julie R. Enszer is the author of four poetry collections, including Avowed, and the editor of OutWrite: The Speeches that Shaped LGBTQ Literary Culture, Fire-Rimmed Eden: Selected Poems by Lynn Lonidier, The Complete Works of Pat Parker, and Sister Love: The Letters of Audre Lorde and Pat Parker 1974 – 1989. Enszer edits and publishes Sinister Wisdom, a multicultural lesbian literary and art journal. You can read more of her work at www.JulieREnszer.com.