“REVENGE REVENGE remember.” —Rokhl Auerbach

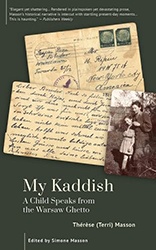

These words, written in haste on July 26th, 1942, voice one writer’s desperate plea to future generations of Jews. Trapped inside the Warsaw Ghetto, and facing transport to Treblinka, Rokhl Auerbach and other members of a secret writer’s group called Oyneg Shabes buried their written records of the ghetto. Warsaw Testament, available in English for the first time thanks to Samuel Kassow’s translation, is a collection of Auerbach’s contributions to this group.

Auerbach was an active member of the thriving Yiddish arts scene in Warsaw before the war. When Germany invaded and trapped the city’s Jews inside the ghetto, Auerbach was recruited to join Oyneg Shabes, an underground group of ad hoc archivists who raced to record every aspect of ghetto life. Led by Emanuel Ringelblum, the collective recognized that their own chances of survival were slim, but that they had an opportunity to make sure their stories did not die with them. “[I]n a time of dreariness, bloodshed, and hunger, the writer suddenly realized that his talents are needed,” Auerbach writes. “He saw that he could reach out to a future he might never live to see.”

In addition to their own contributions, this group solicited written testimonies and art from a wide cross-section of the ghetto’s Jews, which were eventually sealed in milk tins and buried. Two of three caches have been found to date that, together, house over thirty-five thousand pages of material.

Warsaw Testament contains many of Auerbach’s writings from this period, as well as a few postwar essays. Readers will be moved by her on-the-ground reporting of daily life in the Warsaw Ghetto and by her “uncontrollable impulse,” as Auerbach put it, to record as much as possible for posterity. One of the most fascinating — and important — aspects of Auerbach’s writing is her tendency to describe the people she met in the ghetto, especially through her job managing a soup kitchen. Auerbach knew that she was writing their eulogies, even though some were still alive at the time of writing.

Kassow’s translation retains the punchiness of Auerbach’s prose. Even when she’s writing about something as seemingly mundane as soup, her words allow readers to understand both the life-and-death nature of everything that happened within the ghetto walls and the deep angst she felt about the annihilation of the Yiddish arts. Warsaw Testament also includes an excellent introduction by Kassow that contextualizes Auerbach’s writings and Oyneg Shabes’s mission. Through this volume, Auerbach — who was one of only three Oyneg Shabes members to survive the Shoah — finally gets her due as a wartime writer and activist, for preserving the personal narratives of the Jews who lived and died during the Holocaust.

Warsaw Testament is a welcome addition to both personal and academic libraries — not just as a historical relic of the Warsaw Ghetto, but as an elegy to the Yiddish arts scene that was so important to Auerbach. For her and the other members of Oyneg Shabes, the way to revenge was through recording the voices that Nazis tried to silence. For them, and in Warsaw Testament, remembering is revenge.