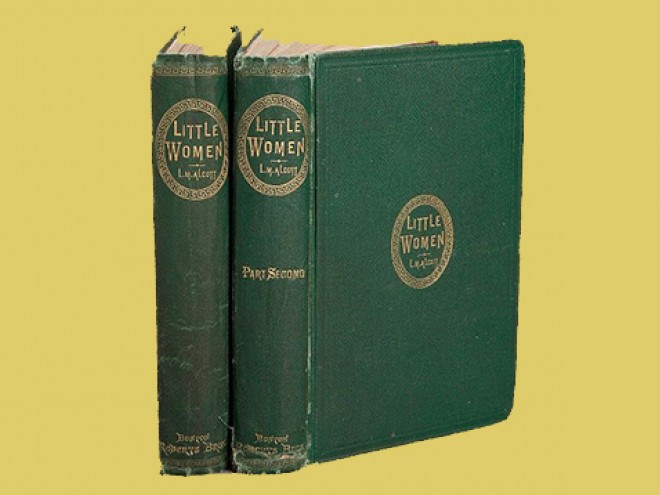

Simon Deutz (1802−1844), 1800s, Ader Paris

Portrait of Caroline Ferdinande of Bourbon-Two Sicilies (1798 – 1870), Duchess of Berry, Thomas Lawrence

What does it mean to write about a Jewish traitor?

This is the question I asked myself as I began researching Simon Deutz — a rabbi’s son who made headlines around the world when he betrayed the duchesse de Berry in 1832 — for my book The Betrayal of the Duchess. Despite Deutz’s infamy at the time, his story has been largely forgotten. Historians have been reluctant to resurrect it, afraid that it would only perpetuate stereotypes of Jewish greed and perfidy. But in fact, a very different lesson can be drawn from his case.

The Revolution of 1830 in France forced the Bourbon royal family into exile, replacing them with their more liberal cousin, Louis-Philippe d’Orléans. Two years later, Maria Carolina de Bourbon-Sicile, duchesse de Berry, launched a bloody civil war to reconquer the throne for her eleven-year-old son. Acting as her son’s prospective regent, this unlikely military commander managed to assemble a loyal band of partisans, drawn from some of the most influential noble families in France. For the most part, she chose her associates well: they were all willing to die for her and for what they considered to be the “legitimate” monarchy. She made one miscalculation and it would prove her undoing.

On the surface, Simon Deutz was an unlikely candidate to become the confidant of the duchess. A commoner and an immigrant to France from Germany, he had grown up in the Marais in central Paris, at the time a poor neighborhood. By the time he reached his twenties, he had failed at a number of different professions. Not the type to associate with royalty. But what made the duchess’s choice most surprising was that Deutz was originally a Jew. Indeed, his father, Emanuel Deutz, was the chief rabbi of France. But Simon was born in 1802, eleven years after France became the first European country to grant Jews full civil rights; by the time he came of age, a new generation of Jews had begun to move from the margins into the mainstream of French society.

The betrayal of the duchess had become a myth that could be used by antisemites to convince a gullible public to accept their lies about Jewish avarice and duplicity.

Simon Deutz took full advantage of the opportunity to reinvent himself. In 1828, he deeply wounded his father — and shocked the French Jewish community — by converting to Catholicism. So big a stir did the abjuration of the chief rabbi’s son create that Pope Gregory XVI welcomed him in Rome and put him on the payroll of the Holy See. And it was the pope himself who introduced Simon to the duchess as someone she could trust as she prepared to launch her civil war.

In reality, however, Deutz had no loyalty to family, religion, or political party. He wanted to get ahead and he saw working for the duchess as his opportunity: she even promised to make him a baron as soon as she returned to power. At first, Deutz performed his duties with discretion, carrying her secret requests for aid to the courts of Spain and Portugal. But after she suffered a series of military setbacks and it seemed like her war would fail, he switched sides. In exchange for 500,000 francs, he promised the French Minister of the Interior to lead the police to the attic in the city of Nantes where he knew she was hiding. After a dramatic all-night search, the police eventually apprehended the duchess on November 6, 1832. Deutz collected his money and then watched in horror as the revelation of his betrayal set off what would become modern France’s first antisemitic “affair.”

In the press across France and around the world, a narrative took shape over the next few months that cast Simon Deutz as a monster and a villain. Interestingly, however, it was only right-wing writers, intensely loyal to the Bourbons, who made the link between Deutz’s “treason” and his Jewish background. Disregarding Deutz’s conversion, they repeatedly referred to him as a Jew and more specifically as a modern incarnation of Judas. Victor Hugo went so far as to write an entire poem condemning Deutz, whom he called “not even a Jew,” and a “disgusting pagan.” In popular engravings from the time, Deutz was depicted with features that would later become familiar in antisemitic caricatures — a small stature, swarthy complexion, and thick lips. Fearful of a pogrom, the leaders of the French Jewish community put pressure on Deutz’s father, the chief rabbi, to renounce his son. When the rabbi refused, they attempted to remove him from his post. Simon eventually fled to England and then to New Orleans, where he seems to have died under an assumed name a decade later. His real name remained a synonym for treachery in France into the middle of the twentieth century.

Simon Deutz (1802−1844), 1800s, Ader Paris

Deutz largely deserved his bad reputation. In a self-justifying memoir published in 1835, three years after the affair, he claimed he had betrayed the duchess to save France from civil war, but it was clear that his real motivation was a desire for self-advancement. Even if his crime did not amount to treason against France, as his critics at the time alleged, he remains a deeply unappealing figure — a liar, a narcissist, and a turncoat. This may explain why so few recent historians have taken up this case, despite its undeniable importance for French Jewish history. One historian tried to rehabilitate Deutz by claiming he had not accepted money for the betrayal. However, Deutz clearly did: contained in papers of the Minister of the Interior is a receipt in Deutz’s handwriting for the enormous sum he was paid.

So why revive the case — especially at a time when antisemitism is once again on the rise? Deutz’s fate is worth reexamining because it illustrates something essential about how antisemitism functions. Calling Deutz a scoundrel — as almost everyone did at the time — was not antisemitic. But associating his crime with his Jewishness — as only the right-wing did — most clearly was. By blaming an entire people for the actions of one man, these writers generated the script for later antisemitic affairs. Moreover, the case represents a decisive moment in the development of modern antisemitism: it was the first time that hatred of the Jews became a key part of right-wing ideology in France. Later antisemites would refer back to it as a model.

Indeed, Édouard Drumont, the author of the enormously popular 1886 antisemitic screed Jewish France, which served as a model for Hitler, relished the story of the betrayal. “How all the actors fit their roles!” he said of the duchess and Deutz, who struck him as perfect incarnations of the noble Aryan and the dangerous Semite. Drumont would repeatedly invoke Deutz’s actions to fan the flames of hatred against Jews, helping to pave the way for the Dreyfus Affair. When rumors began to circulate in 1894 that there was a traitor in the army, suspicion fell on Alfred Dreyfus, a Jew, because Dreyfus fit a familiar pattern — an apparent lineage of treachery inaugurated by Judas and continued by Deutz. The betrayal of the duchess had become a myth that could be used by antisemites to convince a gullible public to accept their lies about Jewish avarice and duplicity.

Unlike Alfred Dreyfus, Simon Deutz was not an innocent victim. His story lacks the moral uplift of the Dreyfus Affair: it contains no “J’accuse!” moment of righteous indignation, or happy ending in which good triumphs over evil. And yet there is much to be gained by examining his life. It is only by confronting the past in all its complexity that that we are able to face the challenges of the present.

Maurice Samuels is the Betty Jane Anlyan Professor of French at Yale University, chair of the program in Judaic studies, and founder and director of the Yale Program for the Study of Antisemitism. He is the author of three books, including The Spectacular Past, which won the Gaddis Smith International Book Prize, and Inventing the Israelite, which received the MLA’s Scaglione Prize. Prior to teaching at Yale, he was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania after completing his Ph.D. at Harvard. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2015. He lives in New York and New Haven, Connecticut.