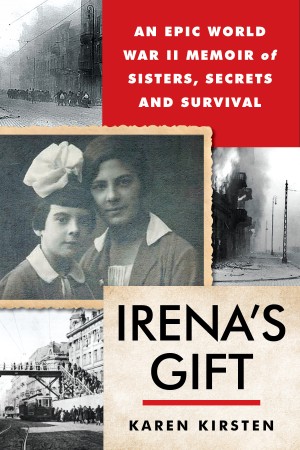

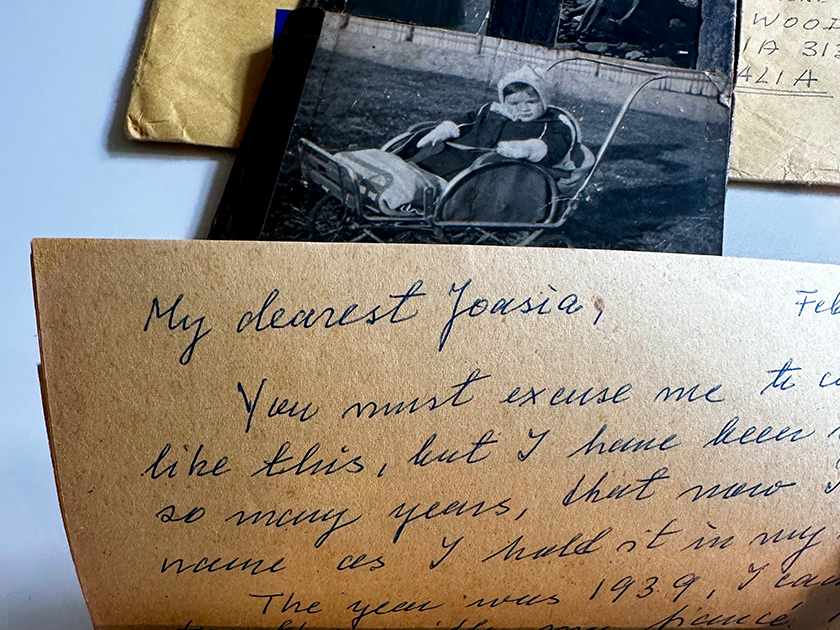

The letter from Canada with photos smuggled through four concentration camps

All photos courtesy of the author

On a chilly November evening in 2011, I was snuggled on my sofa in Boston with my laptop, pounding out work emails. On TV, a young couple on House Hunters was deciding between a three-bedroom condo on a golf course and another with ocean views. With one eye on the TV, I googled my mother’s maiden name, Dortheimer. Perhaps I needed a distraction from work. More likely, I was thinking about my grandmother, Alicja. She’d passed away recently.

I clicked on one of the links. A US Army film clip begins playing, showing Dachau days after it was liberated by the Americans. The film was shot by Hollywood directors, John Ford and George Stevens. The camera pans across a crowd of men wearing shapeless, worn shirts, numbers stitched on their chests. It zooms in on one of the men. His face is pale. His chin is covered in stubble. His brows are deeply furrowed, his cap frayed. I stared at my grandfather, Mietek Dortheimer, thirty-four years old, a stripped uniform hanging large on his eighty-three pound frame.

“Why are you here as a prisoner?” the interviewer asks.

“Because I am a Jew,” my atheist grandfather says.

No one in my family had ever seen the film nor knew anything about it. As a child growing up in Australia, my grandparents didn’t discuss the camps. They brushed off my questions. My grandmother, Alicja, told me she’d tattooed her phone number on her forearm, so she’d never forget it. I’d never heard of Hanukkah until I moved to Boston for a work opportunity when I was thirty-two. In Boston, Jewish people I met spoke with American accents, not Polish ones. One neighbor on my leafy street invited me to her son’s bar mitzvah. Another invited me to Passover and showed me how to dip parsley into salt water to remember the tears our ancestors shed. These experiences with my Jewish coworkers and neighbors brought back memories of my grandparents’ silences. Their hushed conversations. The sound of my mother sobbing through my bedroom wall.

Let me back up a bit further. The truth that I would come to understand is that my grandparents were hiding more than what happened to them in Auschwitz and Dachau. Their secret threatened to undo my mother, as it has nearly undone me. When I was nine, my mother received a letter from a stranger that changed everything she thought she knew about her family. In this letter, the stranger told my mother that her biological mother, Irena, had been killed by the Gestapo in occupied Poland, and that the parents who’d raised her — Mietek and Alicja — were actually her aunt and uncle. Another shock – – the letter revealed that before Mietek and Alicja were sent to Auschwitz, the Polish police arrested them and took them to Radom Gestapo headquarters. Here they endured long weeks of interrogation, during which Alicja negotiated with a notorious SS officer to save my mother’s life.

My mother kept all this secret from me. She’d promised Alicja that she would, but also declared that she wouldn’t lie to me. At thirteen, after I asked an innocent question, I learned that the grandparents I adored were not mine.

I’ve come to understand that family is less about a name on a paper, though, and more about moments of joy and shared memories. Moments we look back on over and over. Consequently, I will always think of Alicja as my grandmother. She treated me like a princess. She’d bake me cakes, shop with me at Polish and Hungarian food stores, dress up to take me to the ballet and symphony concerts, and collect seashells with me on the beach with her poodles. Eventually, she trusted me with her memories. Years after Schindler’s List liberated her to tell only me about Auschwitz, she let me interview her. Yet she withheld affection from my mother.

My mother had always believed that after the war, she’d been reunited with the wrong parents. Mietek and Alicja dismissed her nightmares of armed men in jackboots and of hiding in dark rooms. They adored her brother, but, she claimed, they beat her. My mother forged her way through life feeling alienated, even after she married and started her own family. While the letter had revealed the truth about her biological parents, it provoked baffling questions: Why did Alicja and Mietek hide the truth? Why did they treat her so unkindly? And why, if they appeared to dislike her, did they risk their lives to save her?

Alicja and Irena

My discovery of the Dachau video marked a turning point. I could continue to pursue my career as a marketing executive. Or, I could pursue answers to my mother’s questions, and my own. I lay awake at night thinking about Alicja. The gaps in her stories alarmed me more than her graphic descriptions. Why did she hate the man who sent the letter, and why did he give his daughter away?

And so, I embarked on a research journey, pausing my career. I walked around Warsaw, Kraków, and Auschwitz, listening to Alicja’s interviews through earbuds. I aimed to verify recorded family interviews against historical accounts and other survivor’s testimonies. For years I scoured archives across the globe, including ones housed in Poland, Berlin, Washington DC, Canada, and Australia. I filled some gaps in my grandparent’s stories with archived documents, artifacts, photographs, film footage, letters, diaries, and newspaper articles. With help from historians, online groups (including forums obsessed with Nazi history and memorabilia), and new Polish friends, I dug deeper into the past. I learned about the Radom prison and nearby Gestapo headquarters, where five hundred resistance members were held and tortured. Only ten survived. My grandfather was the only Jewish one. But what interested me most was the remarkable heroism of a number of Polish people who saved my mother.

The biggest challenge in writing Irena’s Gift: A WWII Memoir About Sisters, Secrets & Survival, was incorporating ten years of research into the story of a daughter who unconsciously wanted to heal her mother’s pain. Maybe I was writing for myself as well, to understand what it means to be Jewish given I knew little about Jewish culture, and my mother — who was hidden by Catholic sisters for a time — raised me Christian.

Because I wanted fiction and nonfiction readers alike to connect to the choices people make during and after war in order to survive, I composed deeply researched scenes steeped in rich details, from the glittering concert halls of interbellum Warsaw to post-war Germany. But I also had to write a mystery, about the messiness of family and of complicated mother-daughter relationships. I had to expose love and betrayal. I had to write about the lies we tell to protect ourselves and those we love.

It never occurred to me to fictionalize my family’s remarkable tale. It would have betrayed the promise I made to Alicja. On the last day I interviewed her, she said she worried what happened to her would happen again.

“Do you think someone will want to know all this?” she asked in her thick Polish accent, that even today reminds me of her borscht and poppyseed babka.

“Yes,” I said. “I do.”

Karen Kirsten is a writer, refugee advocate and genocide educator who lectures on the topics of hatred and reconciliation around the world. Her work has appeared in Salon.com, The Week, The Jerusalem Post, WIEZ in Poland, Boston’s National Public Radio station, The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald. Her Best American Essays-nominated piece, “Searching for the Nazi Who Saved My Mother’s Life,” was selected as a Narratively Best Ever story. Raised in Australia by a mother who was a Holocaust and grandparents who silenced her questions about concentration camps, Karen lived amongst refugees who were hiding horrible secrets while trying to rebuild their identities. After discovering her grandparents were not her biological grandparents, she traveled the globe to uncover her family’s hidden past. She has lived in five countries across three continents and now calls Massachusetts home.