Bruce Fritz, U.S. Department of Agriculture, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Nine years before her death, author Bette Greene (1934 – 2020) sat down for a short interview in which she implied that her acclaimed novel, Summer of My German Soldier, was largely autobiographical. Greene emphasized the importance of telling the truth — since it was only shame, and fear of causing harm, that caused her to suppress certain facts.

Like protagonist Patty Bergen, a twelve-year-old Jewish girl living in the repressive fictional town of Jenkinsville, Arkansas during World War II, Greene helped a German prisoner of war to escape. In the interview, she described the sense of relief she felt as she opened up about this lifelong secret. Given that Greene, born Bette Jean Evensky in Memphis, was Jewish and raised in Parkin, Arkansas, this revelation may seem less than surprising. Yet the truth she felt compelled to announce was more complicated. The real revelation of her coming-of-age story was that Jewish parents, like any parents, could be selfish and uncompassionate. The German soldier of the title — and Patty’s dangerous friendship with him — becomes not only a refuge from her punitive family, but also a kind of literary revenge on Greene’s own Jewish parents, who failed to nurture her.

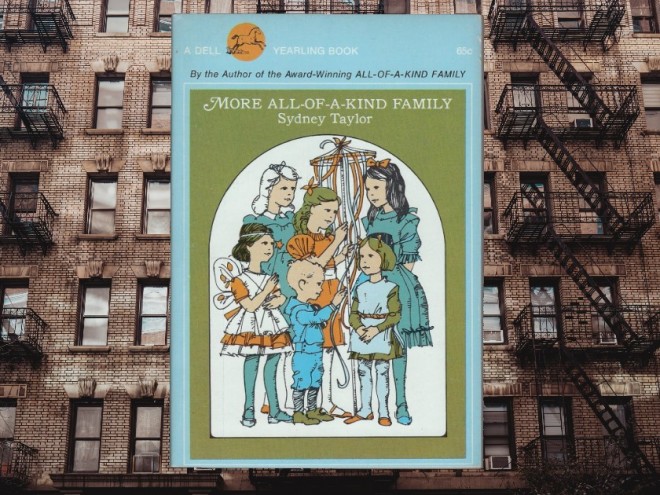

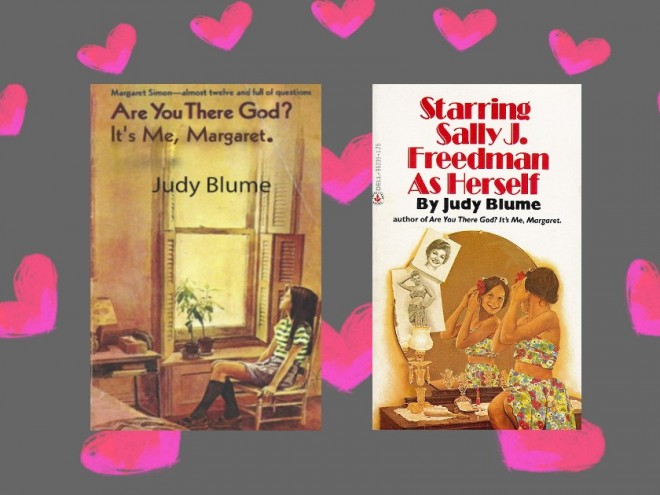

Published in 1973, the book is a notable departure from earlier Jewish American fiction for young readers. Unlike the warm and religiously observant family of Sydney Taylor’s All-of-a-Kind series, or even the interfaith Simons in Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret, the Jewish characters in Summer of My German Soldier are broken individuals. Plagued by antisemitism, they don’t view their Jewish identity as a source of pride. Patty’s parents are cruel, even abusive. Isolated and lonely — especially during the summer, when her classmates are at Baptist camp — Patty is intrigued to see a trainload of German prisoners brought to town for their incarceration in a military camp.

The book takes place in the 1940s. POW camps were often located in the less densely populated South, with several established in Arkansas. There were few successful, or even attempted, escapes from these institutions, and none documented in the ones near Greene’s childhood home. Had a twelve-year-old girl hidden a prisoner, a key plot point of Summer, it would have been widely reported at the time. Greene embedded her childhood pain in a cast of carefully crafted and realistic characters, but her collaboration with an escaped POW, his subsequent death, and her own incarceration in a juvenile reformatory were likely fictionalized. The soldier, Frederick Anton Reiker, was as unusual a feature of middle-grade and YA fiction as was Greene’s unflinching picture of a dysfunctional Jewish family.

The German soldier of the title — and Patty’s dangerous friendship with him — becomes not only a refuge from her punitive family, but also a kind of literary revenge on Greene’s own Jewish parents, who failed to nurture her.

Patty is a child desperate for attention and love, and her point of view is a classic example of an unreliable narrator. When the POWs arrive, the ignorant, and deplorably racist, white residents of Jenkinsville seem to ascribe the worst motives to them. Patty, on the other hand, sees them as innocent: “I tried to read their faces for brutality, terror, humiliation — something. But the only thing I sensed was a kind of relief at finally having arrived at their destination.” When a woman shouts “Nazis!,” a prisoner’s response is to smile and wave at her.

One day, as the group of POWs is escorted to Mr. Bergen’s store to shop for sun hats, Anton Reiker stands out. While the rest have blond or light brown hair, he alone has dark hair. He is fluent in English — his mother is from Britain — and is asked to translate. So singular is his skill that “ … at his approach the men parted like the Red Sea for the Israelites.” Later in the book, when an FBI agent asks Patty to identify a photo of the escaped prisoner, she hesitates, responding, “I don’t remember his hair being so dark.” By giving him physical qualities that set him apart from other Germans, Greene has offered him a hybrid identity, even elevating him to the level of Moses himself. When Patty hides Anton after his escape, he learns that she is a Jewish, a fact he finds to be amusing and ironic; his “strong baritone laughter flooded the room.”

In contrast to Anton, Patty’s father is emotionally damaged. He mocks Patty, and often beats her with a leather belt for alleged disobedience. Anton is appalled to witness this abuse. In The New York Times, journalist Peter Sourian concisely summarizes the contrast between the two male characters: “The prisoner, son of a professor at the University of Göettingen, is an anti-Nazi, while Patty’s father is very much a Nazi, and part of Patty’s trouble is that she keeps on being able to tell who is the real Nazi in spite of herself.” Today, reading these words delivers a shock: they simplify a Jewish child’s moral dilemma and fail to provide context.

The only kind Jews in the novel are Patty’s maternal grandparents. Her grandmother buys her books and cooks her traditional Ashkenazi foods. They are concerned about the attacks on Jews in Europe, unlike Patty’s mother, who complains, “Why do we always talk of war … why don’t we ever talk about happy things like clothes or parties?” (By the mid-1940s, this obtuse attitude would have been relatively uncommon among Jewish Americans.) When Patty is taken into custody, neither grandparent is suspicious of Anton; her grandmother dismisses the entire event as mishegas, and calls for understanding among all people, “no matter what faith or nationality.” Greene seems to have been unable to imagine Jewish characters who were both protective of their own community and receptive to the wider world — they were always one or the other.

Aside from Anton, Patty’s strongest source of validation is Ruth, the family’s Black housekeeper. Kind, dignified, and self-assured, she is able to understand Patty’s suffering and respond with love. She is also a deeply religious Christian, and interprets Anton’s behavior through the lens of sacrifice. Visiting Patty in the reformatory, Ruth identifies Anton as a Christ-like figure, referring to his anguish when he witnessed Patty’s father beating her: “And I saw his face … it said: ‘I’d give my own life to save her.’”

Summer of My German Soldier is among the first American books for children and young adults with central Jewish characters whose traits are overwhelmingly negative. Greene may have believed that she had hidden the realities of her own life, but it took tremendous courage to reveal that Jewish families are not always a source of strength. The improbable character of Anton Reiker, a prisoner far nobler and braver than any of the book’s Jewish characters, is Greene’s answer to the parents whose home was a virtual prison.

The Jewish lawyer hired by Patty’s family to (unsuccessfully) defend Patty accuses her of betrayal: “Young lady, you have embarrassed Jews everywhere. Because your loyalty is questionable, then every Jew’s loyalty is in question.” More than fifty years later, readers of Summer of My German Soldier may judge the impact of Bette Greene’s novel to be far more complex.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.