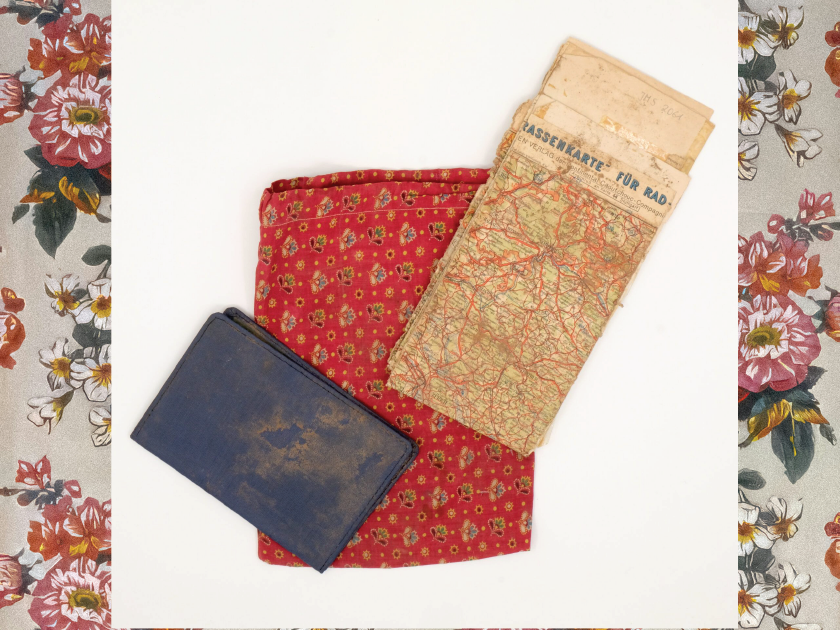

Objects used during Cioma Schönhaus’ escape: road map, document case, and the chest pouch in which they were kept, now in the collection of the Jewish Museum of Switzerland.

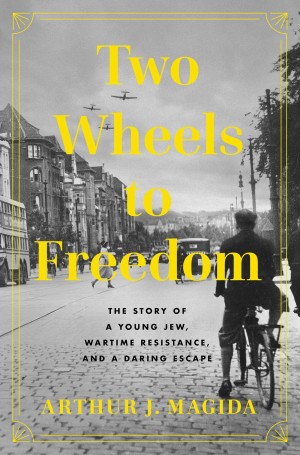

Two Wheels to Freedom, my new book, is my third nonfiction attempt at wrestling with the horrors unleashed by the Nazis. The story in each of these books I discovered accidentally, though each is subtly entwined with the other as part of a larger research journey that has brought many surprises – personal and professional – along with it.

For the first of these books, The Nazi Séance, I didn’t google “Jewish mind reader who stupidly got too close to some of the top Nazis.” I came upon the story of Erik Jan Hanussen while reading a book about the infamous Indian Rope Trick. Along the way, the author breezily referred to “Hitler’s Jewish mentalist,” an entertainer with his own unique theory about how the Rope Trick was done. Instantly, I thought, “That’s who the author should have written about. Not about a trick which few people have ever heard of.” So off to Germany I went to learn about Hanussen, Nazis, and mind reading.

The next of my books about Nazis began when two friends described their new documentary that would soon be on PBS–Enemy of the Reich. My friends mentioned Noor Inayat Khan, a Sufi woman who’d been a spy in a secret British agency, the Special Operations Executive, during the war. Neither Khan nor the SOE rang a bell, but since I’d long been interested in various forms of mysticism, I knew at least that a Sufi was a Muslim mystic. I perked up when my friends explained that Khan was the daughter of Hazrat Inayat Khan who I was aware had brought Sufism to the West in 1910. For his daughter to be a British spy made no sense – mystics often distance themselves from wars, violence, and other troubles of the world. On the other hand, Khan’s spying made complete sense – Sufis advocate for selflessness and compassion. In that case, how could Khan not try to make the world a better place, a safer place. I embarked on writing that book, Code Name Madeleine, almost immediately. Had I not already been in Germany for The Nazi Séance, I would not have moved with such alacrity. The Third Reich’s sins had frightened me for years, yet several research trips to Germany for my biography of Hanussen had convinced me that current generations are as repelled by Germany’s past as I was. I was also deeply impressed with their willingness to confront their nation’s history, as scorching and as uncomfortable as it may be.

And how did I learn about Cioma Schonhaus, the hero of Two Wheels to Freedom, my current book? That was more complicated than the two books I’ve mentioned. While researching one of those books in Berlin, I passed a plaque on the wall of an entryway to a courtyard. On it was a large portrait of Anne Frank. Intrigued, I walked into the courtyard and found a foundation named after Anne Frank. That was appropriate – this was Berlin, after all. There was also a well-preserved workshop that had made brushes and brooms, manufacturing them even during the war. Its owner, Otto Weidt, had hired only Jews who were blind. At night, Otto’s friends hid them in their own nearby apartments.

I was tempted to write a book about Otto until research convinced me there wasn’t enough for an entire volume. Books eat up material and they eat up your life. I learned, though, that a Jew, Stella Kubler, had turned about forty of Otto’s hidden Jews over to the Gestapo in 1944. Kubler survived the war by betraying Jews, ultimately more than several hundred of them. Kubler intrigued and alarmed me, though I concluded that writing a book about her would be too gloomy: I didn’t want to lose myself in Kubler’s grim opportunism for however long it would take to write and research the book.

Kubler led me to Cioma Schonhaus. They’d met in art school around 1941. Two years later, they bumped into each other on the street. Both of them were hiding. Schonhaus, using his training from the art school, made a fake ID for Kubler and saw her once, maybe twice after that. His timing was impeccable. A few months later, Kubler began her career as a greifer, a “catcher” – finding and turning in Jews who were hiding. She never turned in Schonhaus.

Schonhaus’s courage, resilience, cheerfulness appealed to me. I was impressed not only with his fake ID’s that saved hundreds of Jews, and how he sabotaged weapons, but also that he bought a sailboat though he never sailed before and that he had lots of girlfriends, dined at upscale restaurants, and biked 600 miles to Switzerland as the Gestapo closed in on him. The antithesis of Kubler, Schonhaus deserved a book. He has one now, Two Wheels to Freedom.

Writing these three books in fourteen years filled a hole in my life that I didn’t know needed filling. My generation rarely heard about the Holocaust from our elders; we barely spoke about it among ourselves. It was too fresh, too traumatic, too beyond words to be put into words. I knew it happened, of course. But it was in the background, never the foreground. As a kid, I saw one or two people with numbers tattooed on their arms. No one explained why those numbers were there. In Hebrew school, we learned about Abraham smashing his father’s idols and about Moses parting the Red Sea. Nothing about 1933 to 1945.

As senior editor of the Baltimore Jewish Times, I spent a fair amount of time at the Holocaust Museum in Washington before and after it opened, interviewing many of its staff members, discussing exhibits and artifacts, and hearing many stories that had never been told before. I learned a lot. I cried some, too. But then I’d move onto my next story and, in a sense, would leave the Holocaust behind me. After writing three books set during the Nazi era, I’ve more fully found the words, and the strength, to bear witness to what Hitler did. The effect of telling these stories – two involving resistance and bravery; one (Hanussen’s, the mind reader) involving being duped and suckered – has been profound, humbling, and soul changing.

Yet one challenge remains for me: I don’t understand the Holocaust, and I never will. Its horrors are beyond comprehension; its deliberate mechanics and engineering are beyond our grasp.

Arthur J. Magida has been nominated for a Pulitzer and won multiple awards. His last two books—Code Name Madeleine (“absolutely gripping,” “tightly plotted”) and The Nazi Séance (“an astonishing story, brilliantly told,” “haunting, vivid”) — are optioned for films. He’s been a contributing correspondent to PBS’s Religion & Ethics Newsweekly, senior editor of The Baltimore Jewish Times, and editorial director for Jewish Lights Publishing. He lives in Baltimore.