This piece is part of our Witnessing series, which shares pieces from Israeli authors and authors in Israel, as well as the experiences of Jewish writers around the globe in the aftermath of October 7th.

It is critical to understand history not just through the books that will be written later, but also through the first-hand testimonies and real-time accounting of events as they occur. At Jewish Book Council, we understand the value of these written testimonials and of sharing these individual experiences. It’s more important now than ever to give space to these voices and narratives.

In collaboration with the Jewish Book Council, JBI is recording writers’ first-hand accounts, as shared with and published by JBC, to increase the accessibility of these accounts for individuals who are blind, have low vision or are print disabled.

The spring of 2024 seemed a crazy time to take off for six weeks to go to Israel. I had a book coming out soon, I was trying to make headway on an essay collection; I’d fallen behind on a slew of other commitments and, to top things off, my husband and I were facing a mini-mountain of unexpected home expenses that would squeeze our discretionary funds.

But the war with Hamas had been raging for months and all I did was consume the news. Friends were going to Israel to pick tomatoes and sort clothes for evacuees. I’d lived in Israel twice in my life; for three years decades ago and, more recently, for five years as a visiting writer at a university. All I wanted to do was get on a plane.

Three days after arriving, I met an Israeli friend at Hostage Square, a plaza outside the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Every Saturday night thousands of Israelis gather there to demand the government do more to release the hostages. After we walked through the heartbreaking art installations, the claustrophobic replica of a tunnel, the fence stapled with posters of the hundreds still in captivity, we went to a nearby cafe.

“So how are you managing?” I asked my friend.

My friend sighed. We had met years before when I gave a talk at the teacher’s college where she worked.

“How is anyone managing?” she said. Then she leaned into the table. “Forget us, what about you?”

“What about me?”

“In America. It’s almost as bad for you there as it is for us here.”

It was a conversation that would be repeated with nearly every Israeli friend I talked to. The hostage posters violently ripped off telephone polls in New York City. The screaming protesters blocking highways and airports. The campus demonstrations that would only get worse. It had shocked my Israeli friends. This was not supposed to happen in America, the country that, despite its flaws, they’d looked to as a model of tolerance and safety for Jews.

At first I waved off their concerns. I’d say something like, “It’s not as bad as it looks. Newspapers and websites make a lot out of it to sell copies and get clicks.”

Then I’d return to my flat and contact my publicist and say, “You know that cultural center you’re thinking of reaching out to for an author talk in such-and-such city, such-and-such college town? Maybe skip it.” My book, Displaced Persons: Stories, is a collection of Jewish stories, half of which are set in Israel. Though it was coming out from a press that had awarded it a literary prize, there was no mistaking the specific subject matter. For months, the literary world had been blowing up. The bookfair of an annual conference for academics in creative writing (8000 attendees) was taken over for two hours by pro-Palestinian demonstrators with bullhorns. PEN America was attacked for refusing to cancel an appearance by Mayim Bialik. My husband said to me: “Those venues probably won’t invite you. Or if they do, no one will come. Or if people come, it might be ugly.” Trying to arrange such appearances seemed unwise.

But then it hit me. How could it be that I even had to think this way? Had I ever encountered such a thing before?

_______________

In 1978, I was a young lawyer in a rural Massachusetts town. Though many of my law school classmates had decamped to Wall Street or Washington, D.C., I’d been drawn to the area’s natural beauty, the low-key lifestyle, and the down-to-earth Main Street lawyering. One December evening, over dinner with a local attorney who worked in Connecticut, the attorney said to me, “The nativity scene on the courthouse lawn – it’s a violation of the separation of church and state. You should write to the Selectmen about it. I’d do it, but I don’t practice in the town.”

I wasn’t so sure. The attorney and his wife were homeowners and paid property taxes; I was just a renter. But I sent a polite note asking the Selectmen to reconsider the display in future years.

Within days an article appeared in the town paper to the effect of Local Lawyer Opposes Christmas.

My boss got angry phone calls. Threatening notes appeared in my mailbox. My phone rang in the middle of the night. I went to stay with a friend. When I told my father about it, he was sorry I had to experience that but not surprised. Though he wore his Jewishness lightly, he and his brothers had changed the family name in the 1930s from Levy to Leegant because of university quotas.

Soon after the article ran, I went to the local Registry of Deeds to file some documents. The man in charge, a middle-aged flirt who liked to wink and gab every time I showed up, took me aside and said that, as a friend, he had to ask: What was I doing? Nobody cared about the First Amendment. Didn’t I understand that this was a Christian country?

_______________

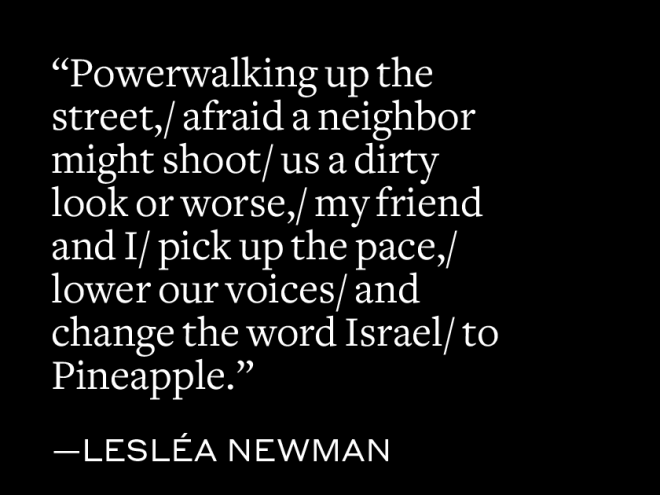

Days after my husband and I returned from Israel, a display of hostage posters on the lawn of a house in my heavily Jewish suburb was defaced. The Massachusetts Teachers Association held a webinar to explain the “settler colonial structure of Zionism” to public school teachers. A reviewer interviewing me about my forthcoming book said she needed to be careful not to use certain words when she wrote it up lest the piece attract vitriol or be review-bombed.

Into his eighties and frail, my father, a lifelong New Yorker, refused to stop taking the subway even when it was dangerous because, he said, it was his city, where he belonged. Half a year after my conversation with the man in that Massachusetts Registry of Deeds, I picked up and went to Israel. I thought I’d stay six months. I stayed three years. Unlike my father, I wasn’t sure where I belonged.

Forty years later, bringing my book of Jewish stories out into the world, I’m once again not so sure.

The views and opinions expressed above are those of the author, based on their observations and experiences.

Support the work of Jewish Book Council and become a member today.