Photo credit Zoe Fisher

Sunil woke singing one of his blurry, half-awake love songs: Amy is my cuckoo clock, and I love my cuckoo.

The coffee was already started when Amy emerged from the bedroom and slipped down the stairs barefoot, in short shorts and sleeper T, to get the Globe. Sunil wove into his song her grumpy expression and slept-in hair, her nose reddened from the morning cool.

Amy read every square of the front page, then the travel section. Over yogurt and granola, she mockingly read aloud the last paragraph of the pro-Bush op-ed. Some conservative was arguing that Dubya had significant foreign policy experience because Texas was a border state. A few minutes later, Sunil left to work in Widener, leaving her the kitchen table, the only available workspace in the apartment. Amy — who ran and biked and swam in all the public health charity athletic events (good health, good networking) — always, irritatingly, urged him to walk to the library because he didn’t get enough fresh air and exercise.

An hour later, Sunil was back on his street; he’d forgotten a book. From outside their apartment door, Sunil heard Amy on the phone, “He works so slowly—I’m not even sure what he does all day at the library. How could he not have made any progress in six months — maybe more?”

More. It was more. But she didn’t know that.

He pushed open the warped door. Amy was sprawled on the floor, phone to her ear. He fetched the book and waited until she was done. “Who were you talking to?”

“Monica,” she said. “I realized I couldn’t get married without my sister, so I called to invite her.”

Sunil had been shocked when Amy said she didn’t want her parents at their sudden wedding. The Kauffman’s Orthodox conversion still made her too uncomfortable — she’d broken out into hives when they told her and Monica, three years ago. But that was irrelevant at this moment. “Don’t change the subject,” he said.

“I’m sorry, love. I didn’t mean for you to overhear that. I just feel like I can’t ask you what’s going on because you’re so stressed out. But I should’ve just talked to you.”

“And said what?” He pressed his heels into the cracked floorboards until his toes tingled.

“That you seem to be reading endlessly to keep from writing.”

“You know what I’m doing is really hard, right? Coming up with something new to say after two thousand years of analytic philosophy. It’s not like we have new data to work with, like in medicine. Philosophers have to think up something new using the same evidence we’ve always had.” He winced as he heard himself speak, adding “analytic” like an ass.

Data, in fact, was a point of contention between them. For Amy, “I looked it up,” was a favorite, argument-ending phrase. Religion aside, Amy was like her journalist parents in that she believed most answers were out there in the world to be discovered. Like he used to think about moral truths.

“I know it’s really hard, but if you just keep at it, the writing, the words will come.” She paused. “I wish you had a course to teach. Teaching was so good for you.”

It had been. Sunil’s scholarship, earmarked for minorities, did not allow him to teach, unlike almost everyone else at Harvard, who’d been TFs, teaching fellows. But last fall he had begged Bernardston, the philosophy department chair, to let him do so for just one semester. Bill James, Sunil’s adviser, had strongly discouraged the idea: Sunil needed to devote all his time to his dissertation; teaching was a distraction. But Sunil had persisted. And Lieberman, who could be credited with planting the seed of his dissertation, had supported him; she agreed it would be good for him to explain material to students, and to know if at least the teaching part of the academic enterprise was something that he could be good at.

Bernardston could not bend the rules of his scholarship, but he had offered Sunil a chance to sub for him while he was off at Oxford giving a series of lectures. It would be the most difficult of any teaching situation, at mid-semester, but Sunil had immediately accepted.

The morning he was to lead the class, Sunil threw up his breakfast. His hands shook. Bernardston normally wore jeans and a sport coat to class. Sunil didn’t own a jacket, so he wore his nicest button-down. At some point halfway through, he realized his shirt was misbuttoned, one side dragging lower than the other. Heat flushed through his entire body, but he forced himself to think It could be worse and kept going.

He discovered that it was easy for him to create simple, stark paradoxes for his students. He could make them understand why personal identity was not a simple matter of a singular brain yoked to a singular body. What if brain and body were cloned, was You2 still you? What about memories? If I don’t remember what happened yesterday, is that yesterday-person me? Students had arrived in the classroom with low visors, droopy eyes, yet he had been able to induce many of them to think for fifty minutes. There were awful moments of demoralizing, vacuum-packed silence, but by the end of the class, his prodding had yielded results. Hands in the air!

At the end of the semester, Bernardston had called Sunil in to his office. “I have to say you’ve set up something of a problem for me. Because of the class you taught, now my students are asking for more discussion.”

“So, they got something out of it?”

“I don’t know, but they liked it.” Bernardston smiled.

Now Amy said to Sunil, “When you sit down to write, can you pretend that you’re teaching someone? Could that be a way to reboot?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “But it’s a good idea.” He kissed her on the cheek, and headed back to campus.

Later that day, Sunil sat in on an ethics seminar. It was taught by the abrupt but persuasive Rivka Lieberman. Sunil had taken this same seminar two years ago, during Lieberman’s first year with the department, and the questions it raised had burrowed inside him. Sunil had felt mentally sharper during that class than any other time. Philosophy became urgent.

It had started with J. L. Mackie, an Australian ethicist writing in the 1970s. Mackie asked why there was such variation in moral beliefs among different cultures. Why, for example, did some cultures believe in monogamy and others polygamy? It couldn’t be, Mackie argued, that one culture simply had a better ability to grasp moral truths than another. It didn’t make sense that one culture would be somehow more attuned to what was good and what was bad. This had led Mackie to argue for an antirealist view: the view that moral truths did not exist independently of our beliefs about them. That is, certain actions, practices, and desires were valuable only because humans thought them so: monogamy was good because humans valued the practice, not because it was objectively the right way to live. Sunil had thought Mackie’s reasoning valid, but he was bothered by the premise. Sunil didn’t see such wide variation in moral beliefs. He instead saw strong uniformity and thought that the differences philosophers pointed to were superficial. Didn’t the uniformity mean we were all attuned to the same moral reality? The human burden was to acknowledge and follow moral scripts.

With Lieberman’s help, and drawing on his abandoned pre-med background, Sunil had arrived at a dissertation project that posited evolutionary influences on moral beliefs. But recently his project had stalled. He was now revisiting Lieberman’s course in the hope that Mackie, or someone, would get him going again. Lieberman was not on his dissertation committee, of which Bill James was chair, but, having helped shape his project, one she had suggested was uniquely promising, she claimed to be invested in the outcome. She periodically checked in with him. But the spring semester was now three-quarters over, and Sunil had nothing but his verbal contributions to her class to show for it.

After class, Sunil found Lieberman waiting for him outside the seminar room. Animated, pushing her hair back to show dark brows and a fine, straight nose, she said, “Sunil. Stop and talk to me. What is the problem.”

She was so unnerving. It was disorienting the way she asked questions without the question mark. The way she asked also made Sunil suspect the faculty were talking about him, which rattled him further.

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“You stopped talking in class. You think I wouldn’t notice? First eight, nine weeks you’re jumping in and objecting, you have the books in your hand, I see the marks. But then, the last two weeks, since the readings on antirealism, you don’t say anything and I think that I have made it unbelievably boring.”

“I’ve taken this class before,” he reminded her. He wanted to tell her that he always learned from her, but something made him hold back. He squirmed under her gaze. She was large-boned and large-breasted, with wide hips and a flushed neck that embarrassed him.

Then he surprised himself by now saying something revealing, setting free the worry on the tip of his tongue. “It’s just that this view is messing with my head. It’s making me doubt some pretty fundamental things — like whether we’re justified in holding people accountable for their actions.”

Lieberman nodded. “You’re terrified. The skeptical worry is taking over your life.”

“Yes.” He realized how much he wanted to impress her, to prove correct her faith in him.

“This is normal,” she said, then tilted her head to look at him quizzically. “Do you believe our philosophical views should guide our lives?”

“Yes, sometimes.” His stomach began to turn.

“Then you should prepare for a revolution, my friend. Perhaps for anarchy.” She was teasing, in her unfunny, Israeli way. She smiled like a wolf.

Sunil was convinced that evolution provided a cohesive universal story about how humans came to share a set of moral principles, but the conclusions were dark and left him feeling alienated, unmoored, and nauseous. Perhaps the way Amy felt when confronted with her parents’ new beliefs.

He should take this opportunity to talk with Lieberman. Because the anxieties about his project seemed only to be relieved by airing them in conversation. Not by working alone and writing.

But now, instead of inviting him into her office, she said, “When you are ready to talk, let me know.”

He nodded.

Then she added quickly, “Your passion is inspiring,” and turned and walked away.

Earlier in the semester, she had stopped him in the hall to tell him she’d been thinking about something he had said, and the intoxicating pride and excitement had carried him for hours. Now her abrupt goodbye left him standing alone, useless.

He had to get out of here. Sunil barreled down the hall toward the common room, where his friend Andrew was waiting. Then he pulled Andrew by the arm, out of the building onto the street.

Daily, Sunil saw examples of what he’d turn into if he didn’t finish his dissertation. They were the slight, ghostly figures of the Double-Ds. Harvard was notorious for letting people continue for ten or eleven years. One guy had entered the program in 1985, fifteen years ago. Another had bragged to him that he was able to live on two dollars a day, which Sunil disbelieved until he saw the man picking through trash cans. Sunil and his friends mocked the Double‑D grad students behind their backs. Yet at the same time, Sunil and Andrew and Erik were afraid of them. The older guys — and they were all guys — knew a lot, they’d read a lot, they’d been to countless talks and dissertation defenses. They knew how to argue. Sunil envied their alacrity and sharpness.

Years ago, toward the end of his sophomore year of college, Sunil had called his father from a pay phone. I quit!, he’d yelled over the beer pong being played down the hall. He’d enrolled in the pre-med track (where he’d studied evolutionary biology) to please his dad, but he had hated the classes, found them stultifying and difficult. To be a doctor, he’d discovered, you had to have many webs of detailed knowledge at your fingertips. You had to render a response in seconds. Sunil had not been able to summon whole biological processes at once, was minutes behind his classmates in arriving at an answer. Everything was so damn fast, and it made him feel trapped and stupid. He had grown to hate the word answer, the word evidence. He instead felt compelled by philosophical inquiry, one in which our most fundamental impulses and assumptions were questioned and explored. In which progress meant intellectual discovery, rather than a body of knowledge learned, or even a life saved.

Rosie’s was strewn with peanut shells and smelled sour, but there were free pretzels and three-dollar pitchers before four. Their beer arrived with mozzarella sticks, courtesy of their waitress, a mousy undergrad. Sunil wasn’t hungry, but he ate. It was his mother’s ingrained injunction: food wasn’t worth eating when it cooled past piping. He swallowed roughly as the cheese sticks scratched his throat.

“Today I ran into Double‑D 36,” Andrew said. They’d discovered Doug Berman’s age by grossly flattering the department secretary. “He was pulling hard-boiled eggs out of his pocket and peeling them—eating them — on the street.” His face turned gleeful. He patted Sunil on the shoulder. “Don’t worry, I won’t let that happen to you.”

“At least poke your head into my cardboard box, check my pulse.” Sunil drank his beer, shifted in the hard wooden booth. Then he announced, “Amy and I are getting married.” It was the first time he’d said it out loud, put those striking words together in a sentence. But he didn’t get the charge from them he’d expected. He still felt awkward, nervous. Were they making a mistake?

“Hey! That’s some good news! What did her parents say?”

Andrew had been the one to point Amy out in the café where they met. She was in the thick of a spirited game of timed Scrabble with her roommate. Blond, petite, color in her cheeks and forehead, Amy was often told she didn’t look Jewish, which annoyed her and set her apart from her sister, who had green eyes and curly, dark hair. Amy was five years younger than Sunil, but driven, ambitious, certain. When he was her age, he’d been flat, directionless. Amy’s dreams had shape and promise.

“She doesn’t want to invite her parents to the wedding. She’s worried a civil ceremony would only offend them, so we’re not going to tell them until it’s done. It’s the first major decision she’s ever made without her parents.”

“Won’t that be worse? Them finding out after the fact?”

Sunil nodded. “Probably. Especially because she wants her sister to be there. Which means her parents will feel even more slighted. It’s just conflict avoidance. Amy hates fighting with her parents. Their conversion made her angry, but she doesn’t want to show it because she’s worried it will put more distance between them.”

“It sounds like disagreements with the Kauffmans are inevitable,” Andrew said. “I’m thinking of that ‘anti-God’ conversation you told me about.”

“Exactly,” Sunil said.

The Kauffmans liked Sunil — Ariel affectionately called him “duckling” because of his boyish face and out-turned toes — but he wasn’t a Jew, and they were skeptical of his moral compass. During a bitter spell this past winter, over a meal at Legal Seafood, Ariel had said to Sunil, “I know you are an ethicist, this is what you study. But what do you believe? I’ve read that Jains aspire to ‘the three jewels’: right belief, right knowledge, and right conduct. But you say you’re not an observant Jain.”

Sunil had told her that he did not believe in transcendental codes — laws that came from a divine power. “So you’re both anti-God and amoral,” Ariel said. “Because morality comes from God’s commandments.”

Sunil had responded, gently, that he could not be against something that didn’t exist. And before he could address the charge of amorality, Amy had exclaimed, “Mom, how can you say that!” The meal had ended with a no-hard-feelings sharing of creme brulee, but Sunil was left with a worrisome taste in his mouth. He didn’t know whether the Kauffmans had felt the same.

Sunil slowly shook his head. He said to Andrew, “I have no idea how this is all going to go down.”

“Well, they are out of the country, right, in Israel? Aren’t yours, too?”

“They left for Nairobi a couple days ago. They’ll be gone for two weeks.”

“Maybe that’s your excuse?”

Sunil sighed. “Not one that holds much water.” They would have to defend themselves to both of their parents, sooner or later.

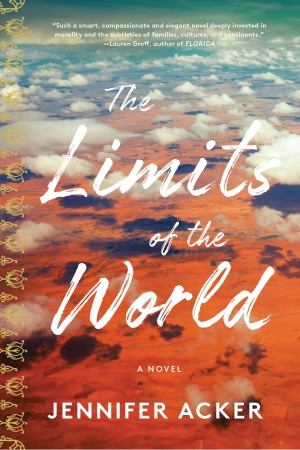

Jennifer Acker is founder and editor in chief of The Common. Her writing has appeared in the Washington Post, Literary Hub, n+1, The Yale Review, and Ploughshares, among other places. Acker has an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars; she teaches writing and editing and organizes LitFest at Amherst College.