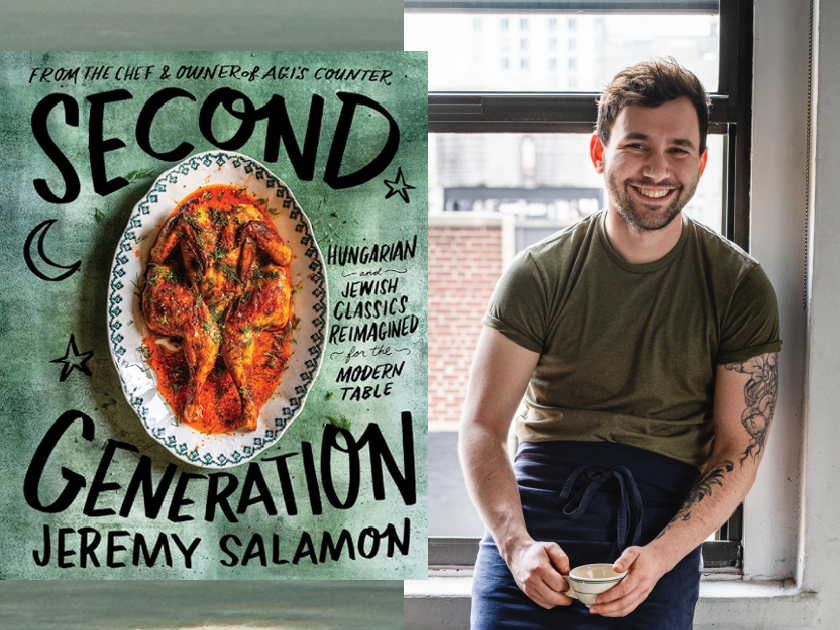

One of my earliest memories is of my little legs running up a four-story walk-up in Boca Raton, where Grandma Agi was waiting at her front door, calling out “Csillag!” She wore big fashionable glasses, a leopard-print housecoat, and fuzzy slippers. The apartment had a thick smell of frying pork cutlets, her rántott hús. She’d hand me a chocolate egg cream, usher me and my older brother, Jordan, into the kitchen, and feed us until we were plump. Dessert was almost always palacsinta spongy egg crepes that looked like yellow moons with brown craters spattered about. She let us stuff them with nuts, cheese, jam, sugar, and syrup.

Grandma Agi, my paternal grandmother, grew up in Budapest, Hungary, at the worst possible time, to put it lightly. She survived life in the Jewish ghetto during World War II, the Stalinist regime after the war, and the Hungarian Uprising in 1956, a failed attempt to overthrow the oppressive communists. After decades of hardship, Agi finally decided it was time to flee. On the night she left Budapest, she stopped by her sister’s house to say goodbye. Her sister covered her in a big fur coat, and Agi slipped off into the night, headed for the safety of Austria and eventually New York City.

In a happier time and a happier place, Grandma Agi and Papa Steve met at a dance hall in New York and settled in Queens, running a successful dry cleaning business together. They raised a family and, like all good Jewish Americans, eventually relocated themselves (and their dry cleaner) to Florida. That’s where I enter the picture.

Csillag is the Hungarian word for star. When Agi would call me csillag, it made me feel like my world was magical and full of wonder. As I got older, that sense of wonder started to fade. I was exploring my independence from my family and making my own path in the world. I found my way to New York and landed in some of the toughest restaurant kitchens in the city. If anything is going to knock the magic out of your life, it’s working as a line cook.

It wasn’t until I happened to find the last tattered copy of The Cuisine of Hungary by George Lang sitting atop the sale pile in a Manhattan bookstore that the wonder came rushing back. I had never seen a cookbook on Hungarian food, and I pored over its extensive history of Hungarian cuisine and culture; it was both new and familiar. There were illustrations of kings and queens in extravagant costumes stuffing their faces with palacsinta but also dishes I never knew existed! Chilled berry soups, hearty braises with ripe stone fruits, and layered cakes as tall as a person. All I had known of Hungarian food was fried meat and heavy sauces. I immediately purchased the book.

Csillag is the Hungarian word for star. When Agi would call me csillag, it made me feel like my world was magical and full of wonder.

That day kicked off a decade of my own discovery of what it means to be Hungarian American. Being second generation often means a weak connection to the language, customs, and rituals that make you special and unique. I traveled to Hungary, living there and eating my way through my heritage. I convinced Grandma Agi to give me her recipes (although it took some cognac to coax them out). I layered my cheffy instincts over centuries of tradition. I found my own internal csillag, a guiding star passed through my family and into my own sense of self.

Nana Arlene, my maternal grandmother, was born and raised in the Bronx by Sephardic Jewish parents. She met her husband, my Papa Howie, in Rockland County, New York, where they ran a very successful pharmacy. When my mom was a teenager, they moved to Florida and reopened their pharmacy in a strip mall. Their next-door neighbor in the mall was a dry cleaner run by … Agi and Steve. Nana Arlene and Grandma Agi became chummy, and like good Jewish women, the yenta instinct kicked in, the photos came out, and my mom and dad were matched up by my grandmothers.

My childhood was A Tale of Two Grandmas. Both of my grandmothers are ladies who lunch, ladies who entertain, and ladies who fill up a freezer, ready to feed anyone who walks through the door. Wherever I went, I never lacked a good meal made by loving hands.

As I got older, Grandma Agi would shoo me out of the kitchen, even as I became more interested in cooking. She didn’t understand a man wanting to cook; a man should be cooked for. Instead, it was Nana Arlene who began cooking with me — trussing chickens, baking chocolate cakes, and making peppery vinaigrettes for Roquefort salads. She is an exacting master technician in the kitchen. She saw that cooking was an inescapable part of me and was happy to be my first, and best, teacher.

Second Generation is not my grandmothers’ cookbook, but it is my way of sharing a bit of their magic with you. Hungarian food is extraordinary, unique, and full of old wisdom. I’m reimagining those traditions with an eye toward seasonality, market-driven ingredients, and a touch of millennial flair — mixed in with some classics from the restaurant alongside a few Hungarian-inspired dishes of my own invention — because I want to help bring Hungarian cooking out of the shadows and into the twenty-first century. And all the parts of this book that lean distinctly Jewish are gifts from Nana Arlene. This book wouldn’t exist without the two matriarchs of my family, who taught me that food and love are just synonyms for each other.

Second Generation: Hungarian and Jewish Classics Reimagined for the Modern Table by Jeremy Salamon and Casey Elsass