Jewish Book Council had the opportunity to talk with Marjorie Ingall about the importance of reading for pleasure, Mark Twain’s philosemitism, the history of marketing books to Jewish women, and her parenting guide, Mamaleh Knows Best: What Jewish Mothers Do to Raise Successful, Creative, Empathetic, Independent Children, an excellent and enjoyable resource for Jewish and non-Jewish parents alike.

Nat Bernstein: Nefertiti Austen recently wrote an essay about authoring parenting guides for women of color and how no publisher has embraced that market. Do you see the same scarcity for Jewish women, or has Judaism staked a claim on a parenting technique that has a wider appeal in the publishing world?

Marjorie Ingall: Publishing is constantly seeking the widest audience humanly possible. For Mamaleh Knows Best, there was a constant pushback from my editor, who kept asking, “Why do you want to talk about Philip Roth all the time?” For her, it was not universal; she wanted a book on how to use Jewish parenting to make a good goyish child. And I understand that: publishing is so risk-averse now that a niche market is not going to get you a book deal. I can imagine the same thing is happening if publishers assume that only black women will buy a black parenting book. But the stories of my black mother friends — especially mothers of sons — and how the kinds of worries they have are not anything like the kinds of worries I have, that would be beneficial for all Americans to read.

NLB: Since we’re talking about how to market books, can you share more about the history of marketing books and reading to Jewish women?

MI: When publishing became more scalable — when printing presses became more widespread — in the late nineteenth century, it created a colossal market — and not just within the Jewish community — of translations into Yiddish of popular books, a lot of them Romance novels. I write for the Times Book Review, and I think it’s hilarious that the Times pretends that the Romance genre doesn’t exist. Romance is a humongous part of the publishing market, and that was true in the late 1800s, too! Jewish women drove popular fiction.

We also have, in our spiritual line, tchines, these prayer books written by and for Jewish women, and that too was a huge market. They included prayers for a healthy pregnancy, prayers that your child will marry well, prayers for successful breastfeeding. All of this stuff was part of our culture, and it would be cool if more Jewish women knew about it. There were early marketing attempts to get women to buy these tchines: “Women! If you only have a few pennies, isn’t this a good way to spend them, for your own spiritual enlightenment for the whole future?” (If this is something that interests you, the index in the back of my book will give you a lot more places to go with that.)

NLB: You have a really lovely and clever chapter on spirituality, in which you observe that taking your kids to religious services is like taking your kids to a restaurant?

MI: As your kid gets older, you teach them how to behave. I don’t believe you should whisk your kid out the first time they make a peep, but you also don’t let a kid scream and disturb everyone else’s spiritual experience. The only way to acculturate a kid is by giving them the experience: no one is born knowing how to behave in shul! One thing I think the Orthodox Jewish community, in particular, has done really well is tolerating noise and chaos in shul. The first shul I went to with my baby — I wanted to join a Conservative shul that was closest to my house — I was getting such a fisheye when she made any noise that I never went back. I tried joining the family service, but I felt that it was cliquey. I found another congregation where the women in front of me kept turning around and making googly eyes at Josie out of delight, and that’s such a small thing, but it made all the difference.

NLB: In one of the early chapters of Mamaleh Knows Best, you point out that “The world is constantly telling us we’re doing parenting wrong.” Is that “we” specific to women?

MI: Yes. We’ve all seen the dudes in the playground, and everyone says, “You are so awesome for babysitting your kids.” You’re not babysitting, it’s your child! We also see the eight zillion Disney movies that all miraculously have missing mothers. It’s not just Jewish women, it’s all women who are told that however they’re doing things is wrong, which is a function of misogyny. It’s not unique to the Jewish Mother stereotype: if you troll Buzzfeed and all these other media sites now, you see Tiger Moms and black moms — it’s a mom thing, which is a problem.

NLB: It’s interesting how much this anxiety over perpetual perfection is transmitted to kids — you write that you “worry that kids today don’t want to be beginners, don’t want to be imperfect, don’t want to ever to look clueless.”

MI: We are always newly shocked when there are cheating scandals at all these fancy schools, but it happens because we have told these kids that they’re not allowed to fail. Surveys of American teenagers in general show that they see their parents as saying one thing and really thinking another when it comes to what their values are: when it is “be Number One at all costs,” you set up your kid if not to fail, then to certainly think I have to do whatever it takes to be Number One.

NLB: I love the Yiddish proverb you discovered: “The woods would be very silent if no birds sang except the best.” You include it in a chapter about teaching kids to distrust authority, which I imagine runs counter to a lot of the parenting advice out there?

MI: Kids are expected to know what they want to be really early, and aren’t encouraged to mess around and explore and be dreamers and figure out what they really love and value. I don’t think our culture, or the pop culture they absorb, helps them with that. One of my regular rants is about live-action TV aimed at kids, where being a quirky, weird, geeky kid is a subject of mockery. Historically, Jews have been geeks, and it’s been really good for us! We should encourage our kids to have obsessions and passions and not be embarrassed about them.

Always having a little bit of distance and viewing authority with a gimlet eye has always been a good thing for the Jews, as well. It is certainly counter to the stereotype of the Tiger Mom, where the view is that the classroom is a fiefdom in which you do what your teacher wants. For the Jews, disrespecting authority is a thread that has gone through our culture from the beginning, whether we have lived in a time when we had tension with the ruling parties or during a period in history when we were very acculturated and had powerful jobs within the ruling culture. I think it’s telling that we don’t have the equivalent of a pope, that we are a dialogic and diverse and fractured-in-a-good-way kind of people. For a parent and for a creative or scientific mind, being a little bit of an outsider is a good thing.

NLB: On the subject of distrusting authority… What do you see as the greatest challenge facing Jewish parents in the next four years?

MI: Despite the title being in present tense, the intention behind Mamaleh Knows Best was to look back through Jewish history and examine what child-rearing traits seem to have served us well. I feel like I’m not entirely qualified to talk about politics or the future, but I do think that one thing that has been essential for Jews is that we are a people who take care of others. Mark Twain wrote this great essay about why you don’t see Jewish beggars — and it’s not because there aren’t Jewish poor people, it’s because Jews take care of their community. As we are entering the age of a leader who uses Twitter to say mean things about people, we want to be sure that we are talking to our kids about being kind. There are other political figures we can point to and say, “Look at this mentschy behavior.” Making sure that our kids are aware of other people’s suffering and helping other people ameliorate that suffering will help us all: everybody feels better when they are do something good, and we can all do that as both parents and citizens.

NLB: In the book you mention the Hebrew Benevolent Societies of the mid-nineteenth century, which as you note popped up in Jewish communities across the United States — on either side of the Mason-Dixon line — really quite rapidly. These societies were founded by women! And run by women! And they were actually the first instance of American — not just Jewish, American — women mobilizing and establishing their own institutions and assuming positions of leadership in an organized way: the Hebrew Benevolent Societies were really the first independent women’s movement in American history, and this is what opened the door for women abolitionists and suffragists across faiths within the same generation. Religiously, theologically, these charitable organizations weren’t necessarily shaking up a whole lot, but the social fabric of American Judaism was suddenly and drastically being rewoven by Jewish mothers at the time that Twain was writing: the standards he saw in Jewish communities were set by its women. (And his appreciation for those standards allowed him to recognize and even confront antisemitism in other parts of the world, which you write about elsewhere.)

MI: Also, let’s talk about American Jewish education: no one really talks about it, but so much of where American Jewish education started was from Jewish women. An unfortunate thing I discovered was that the women who created Jewish education and the women who created these benevolent societies, a lot of them weren’t mothers. Just as leaders of the feminist movement were not mothers. It’s really hard to have a career and to “have it all.”

NLB: And to find time to read?

MI: A thread throughout the book is to not be a “Do as I say, not as I do” parent. It’s important that our kids see us reading, and see that we enjoy it, and see us reading for pleasure as well as betterment. I include in Mamaleh Knows Best all the statistical backup about how important reading is, how a love of books increases empathy, makes your kid do better in all aspects of school. International studies that correct for income and background still find that in houses where everybody reads, the kids do better. For Jews in general, we are the People of the Book, and literacy has often been our ticket into another class, or to not being so quickly killed. Reading is really, really important.

And reading at home should serve a very different function from reading at school: at home, you need to create a safe space for your kid to really enjoy reading. They want to read the same book a gazillion times, fine. My librarian friends have so many stories about parents coming in and saying, “She’s ready for chapter books, can you not let her take out any more picture books?” I still read picture books, I still bring home picture books for my 12-year-old, and the snobbery about graphic novels makes me want to cry: all reading is good reading.

NLB: You also emphasize the importance of humor in parenting — and in transmitting values. How do you view the current generation of Jewish comedians in popular culture?

MI: In general, acculturation is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it’s great to have people not killing us, but on the other hand, the distrust of authority and the gimlet eye has worked in our favor: that is a great place for comedy to come from. Comedy is a great tool for questioning authority, for making people like you even when you’re not like them, and for gaining respect. Look at studies about the use of comedy in the office: bosses who have a sense of humor, who embrace a sense of humor, are reviewed much more favorably by their staffs than bosses with no sense of humor or ones who have belittling senses of humor. I think that’s telling.

NLB: I was particularly heartened to read not only how many female comedians you named among the future of Jewish humor, but also how they are changing Jewish humor.

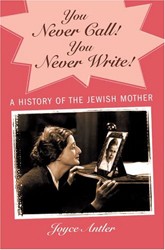

MI: One of the chapters in the book looks at the history of the Jewish Mother stereotype. It’s important to note that the first Jewish Mother in American culture was not this grasping, neurotic stereotype. It was Mrs. Goldberg! This is a woman who was the first recipient of the first Best Actress Emmy, who had a wildly successful radio show followed by a wildly successful TV show. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that she was the executive producer of the show. She created a persona that was, yes, a meddler, but she was smart, she was competent, and she was caring.

Now, we are starting to see American Jewish women as executive producers of comedy shows once again. If you look at the Broad City girls, if you look at Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, if you look at Girls, yes, the mother characters are still flawed, but they are flawed in interesting, complicated ways. And you’re going to have flaws, because comedy requires flaws, but not this knee-jerk, dumb, schticky, mocking, disparaging kind of thing. I would like to think that as more and more Jewish women are in charge of their own storytelling, the Jewish Mother figure will become more nuanced — again.

NLB: You’ve succeeded in raising two kickass feminist daughters of your own. Do you have any advice for raising feminist sons?

MI: Nipping any kind of misogynist behavior in the bud and making sure your kid is aware of sexist language, making sure they treat all people with respect, and talking about women’s achievements despite barriers — they should know that historically it has not been a level playing field for women and men, which is something that anti-feminists will not acknowledge. And, this sounds flippant, but it’s not: the best way to raise a feminist son is to let him have an older sister. I can point to my brother as proof.

Nat Bernstein is the former Manager of Digital Content & Media, JBC Network Coordinator, and Contributing Editor at the Jewish Book Council and a graduate of Hampshire College.