Figure by Ilya Milstein, brushstrokes by Katherine Messenger, design by Evie Saphire-Bernstein

*Updated June 2025*

At this precarious time for LGBTQIA+ people, I’m reminded of the power of literature — of the fact that stories have an unrivaled ability to help us to understand another person’s perspective. The mission of Jewish Book Council’s annual print literary journal, Paper Brigade, is to celebrate the breadth and diversity of Jewish books. Here are pieces from the journal — short stories, interviews, essays, and a comic — that speak to the wide range of queer Jewish literary voices out there, and demonstrate how inextricable they are from the Jewish literary canon.

Illustration by Katherine Messenger

The Diary Beyond Anne Frank: A Conversation with Nina Siegal and Yael van der Wouden by Becca Kantor

Yael van der Wouden’s debut novel, The Safekeep—winner of a National Jewish Book Award and the Women’s Prize — focuses on a relationship between two Dutch women in the 1960s that is profoundly changed by the discovery of a wartime diary. In this conversation with Nina Siegal (The Diary Keepers), van der Wouden discusses how fiction can revitalize queer Jewish stories that have been erased from the past, and how those stories seep into the present day.

Read more in volume 8.

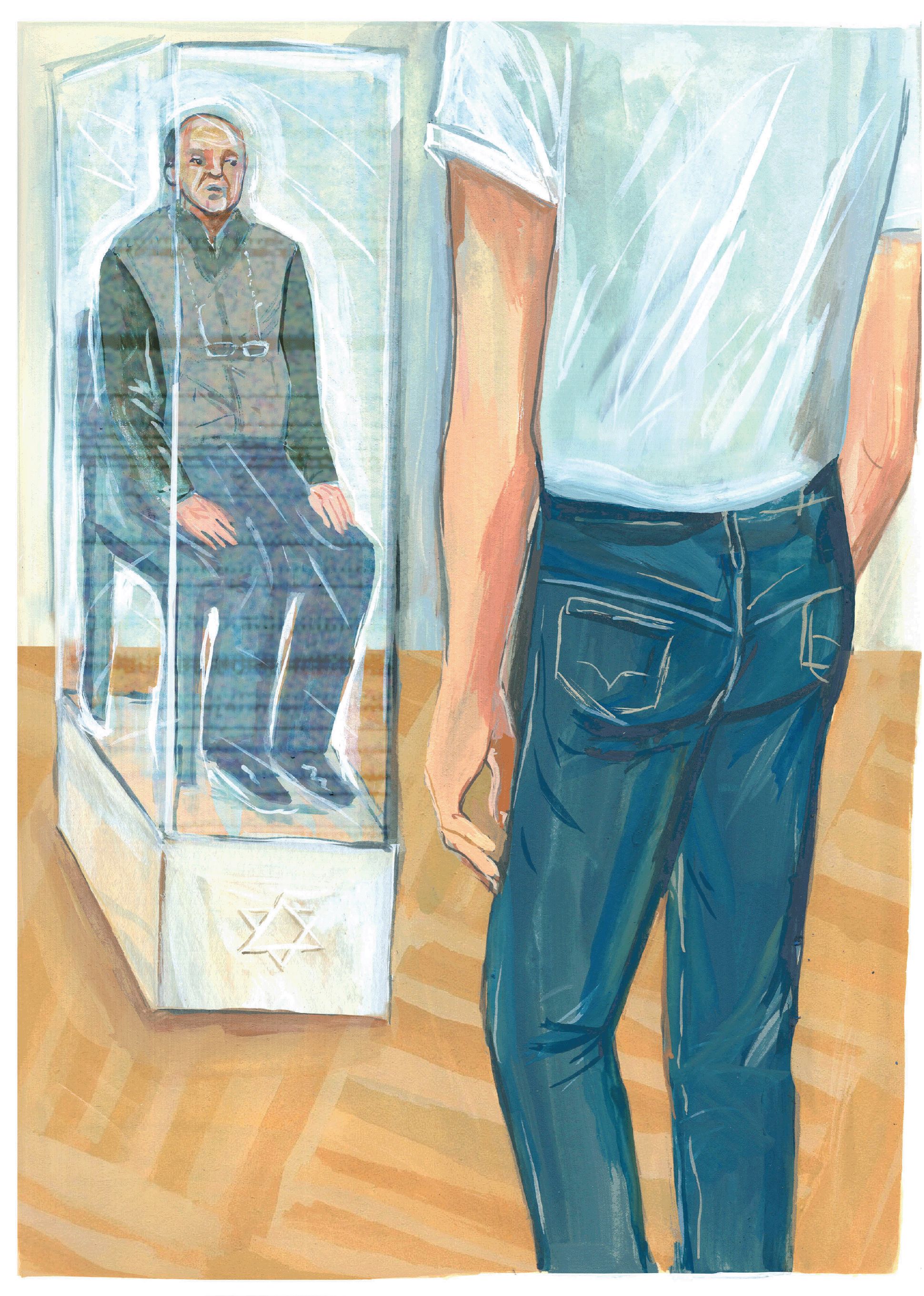

Illustration by Laura Junger

Into the Mud by Yael van der Wouden

If you’re craving more writing by van der Wouden, look no further than this short story in which, she says, “you can see me working out dynamics and themes that become central in The Safekeep.” “Into the Mud” invites us to what could be a European town in the ’90s – except that here, there are dybbuks who hide in microwaves, a rabbi warns his congregation “about the wickedness of the man who wants to control another being,” and Miryam, Debby’s sometimes-best-friend, takes out her frustration with her dysfunctional parents by making golems down by an abandoned lake. Debby is in awe of charismatic, rebellious Miryam, who casually taunts her at school but condescends to spend time with her over the summer. The fantastical elements of this story provide a backdrop for nuanced, suspenseful rendering of a friendship defined in equal parts by resentment and attraction.

Read more in volume 5.

Marigold by William Morris (1834−1896). Original from The MET Museum. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel

Still Life of My Apartment on a Winter Morning by Reyzl Grace

This poem more than earns its title — it’s as finely wrought and visually evocative as a painting. With allusions to everything from klezmer music and the White Rose resistance group, to the author of Bambi and the animator of 101 Dalmatians, “Still Life of My Apartment on a Winter Morning” is a literary ode to a queer couple and the stories that have brought them together. The narrator wonders at a love so attuned to and appreciative of the specificities of their identity and interests, even when they contradict one another. In that sense, the title also becomes a reference to the life the couple can lead within the safeguard of their home — still, steady, consistent, accepting — no matter what the outside world might hold.

Read more in volume 8.

Illustration by Jenny Kroik

“We were waiting in line at the Holocaust Museum on Prinzenstrasse when I realized I had to pee,” is the unforgettable first line of Adam Schorin’s “Holograms.” Our narrator is Sammy, a young and aimless Jewish American expat who lives in Berlin. While visiting an exhibit of holograms of Holocaust survivors with his fellow drag performers, Sammy comes face-to-face with his family’s past and the reality of his transient life. This multilayered story, laced with dark humor, deftly explores the fine lines between Holocaust education and spectacle, the revered and the mundane, drag and transexuality, and privilege and prejudice in Germany today.

Read more in volume 7.

Marble head of a young woman, perhaps a muse, 3rd-2nd century BCE courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1911

Double Muse by Antonia Angress and Emma Copley Eisenberg

In their debut novels, Antonia Angress and Emma Copley Eisenberg explore relationships between queer artists on the cusp of adulthood and their careers. In Angress’s Sirens & Muses, Louisa, a transfer student to Wrynn College of Art, is drawn to her aloof, talented roommate, Karina. In Copley Eisenberg’s Housemates, graduate student Leah is similarly attracted to and inspired by Bernie, a photographer who has recently moved into the West Philadelphia house Leah rents with friends.

In “Untethering the Muse from the Male Gaze,” Angress discusses how her book subverts traditional ideas about the artistic process, and the Jewish history that underpins her book’s themes. Copley Eisenberg responds in an essay, “Artists, Muses — Equals?”, which examines her book’s take on the artist – muse relationship.

Read more in volume 8.

Photograph by cottonbro via pexels

Soviet Stories: Grappling with a Legacy of Trauma Through Fiction by Katya Apekina and Ruth Madievsky

Another National Jewish Book Award winner, Ruth Madievsky’s All-Night Pharmacy, is narrated by a young, bisexual woman trying to make sense of her life in the wake of her older sister’s disappearance, the emotional toll that pogroms and the Holocaust have taken on her relatives, and the allure of a beautiful and seemingly unflappable self-proclaimed psychic. In “No One Disappears Without a Trace” (paired with an essay by Katya Apekina (Mother Doll) in “Soviet Stories”), Madievsky delves into her own relatives’ experiences as Jews in in the Soviet Union, and how their trauma-informed dark humor permeates her novel.

Read more in volume 8.

‘To Celebrate Nonconformity’: A Conversation with David Adjmi and Jack Hazan by Michael Harari

“Look at us: three gay, American Syrian Jews chatting together about our books,” Michael Harari begins this wide-ranging conversation with Jack Hazan and David Adjmi. Together, the writers discuss the traditional communities in which they grew up, their experiences coming of age, and how they found their lifelines through creativity — Adjmi as a playwright and the author of the memoir Lot Six; Hazan as a therapist, baker, and the author of Mind Over Batter; and Harari as a creative director and Jack Hazan’s coauthor.

Read more in volume 7.

T Kira Madden, right, with her sister and her mother

Photo courtesy of T Kira Madden

‘The Secret Was Me’: A Conversation with Dani Shapiro and T Kira Madden by Becca Kantor

As children, writers Dani Shapiro and T Kira Madden navigated difficult relationships with their parents and felt out of place in their communities. Both lost their fathers while still in their early twenties. And for both, a DNA test led to life-changing revelations. In this conversation about their respective memoirs, the two discuss how their personal experiences led them to probe larger questions about identity. Madden notes that her life as well as her book, Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls, resist categorization. “I’m Jewish. And Chinese Hawaiian. And gay. I’m all of these things.”

Read more in volume 4.

Illustration by Laura Junger

Poland Itinerary, Class 3B by Leeor Ohayon

This story follows a British Moroccan teenager, Daniel Amar, on a school trip to Poland. Daniel is bullied because he is Mizrahi and his family wasn’t directly impacted by the Holocaust — in the eyes of his teachers and most of his peers, this makes him less of a Jew than they are. Daniel also nurses an unrequited crush on his popular classmate Josh, and his feelings come to embody his wariness of Ashkenazi culture as well as his desire to be accepted into it.

Leeor Ohayon gives us an incisive look at how Ashkenormative retellings of history can exclude others when they place the Holocaust at the center of Jewish identity. By structuring the narrative as an itinerary, he emphasizes the expectations underpinning the remembrance trip — whether they are about ethnicity, religion, or sexuality.

Read more in volume 6.

View from the French Academy at the Villa Medici, Giacomo Caneva, Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

‘A Might-Have-Been Universe’: A Conversation with André Aciman by Russell Janzen

In this interview, André Aciman reflects on his iconic 2007 novel, Call Me By Your Name, and discusses his decision to return to his protagonists in his 2019 novel, Find Me. In fact, the theme of return runs throughout this conversation; it applies to Aciman’s writing style, the commemoration of Jewish history, and to Oliver and Elio’s relationship. Aciman says that although the two characters are “drifting through life,” sometimes in opposite directions, their connection is “a point of anchorage that they will seek out again.”

Read more in volume 4.

Images by PopTech via Flickr, design by Alex Lezberg

Struggling Our Way Toward Collective Narration by Sam Cohen

“There is both pleasure and difficulty in latching myself to a we,” Sam Cohen observes in this essay, which delves into the way that narrative voice can shape our understanding of Jewish identity. At Passover, Cohen struggles to reconcile her father’s traditional observance with her own understanding of the holiday as a queer, non-religious person. Ultimately, the first-person plural of the seder offers a “kind of magic” — a way for everyone at her table to transcend their differences and cohese into a “motley collective.”

Read more in volume 6.

Study for Obsession by Auguste Rodin, ca. 1896, gift of Auguste Rodin to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1912

Design by Katherine Messenger

Bodies, Borders, and Desire by Ranen Omer-Sherman

This article by Ranen Omer-Sherman examines three novels about relationships between queer Muslims and Jews: Moriel Rothman-Zecher’s Sadness Is a White Bird, Moshe Sakal’s The Diamond Setter, and Evan Fallenberg’s The Parting Gift. Each of these books is elegantly crafted and rich with psychological insight. Together, they give a multi-faceted portrait of what Omer-Sherman terms “the seductive promise as well as the bitter limits of coexistence between Jews and Arabs” in the Middle East.

Read more in volume 3.

Photo by Grace Madeline via Unsplash, design by Katherine Messenger

Mortality Faced You as a Question by Ilana Masad

Written at the height of the Covid pandemic, this essay is a meditation on grief and mourning. As Ilana Masad watches the number of deaths spike, they struggle to comprehend the situation in any way besides the abstract. (“[H]ow can you, or anyone, begin to conjure up the faces of 33,257 people?”) Masad touches on sexuality when they form “a nearly instantaneous crush on” a family friend. The moment is brief, but it isn’t incidental. It’s a reminder that human instincts and emotions can exist even in mass crises.

Read more in volume 4.

Illustration by Laura Junger

The Little Bottles by Weaver

Hinda and Basya grow up as best friends in their shtetl, and then Hinda invokes a piece of magic that dramatically splits their life trajectories. This story is imbued with the satisfying plot and indelible imagery of a folktale. (After reading it, you won’t be able to drink from an uncovered glass without first checking to make sure there isn’t a tiny soul floating around in the water.) But “The Little Bottles” also depicts a bond between two women in a way that few older narratives could have.

Read more in volume 4.

The Deluge Towards Its Close by Joshua Shaw, ca. 1813, gift of William Merritt Chase, 1909, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Design by Katherine Messenger

Queering Genesis by Sarah Blake

Sarah Blake takes us back even further — to biblical times. Her debut novel, Naamah, is a retelling of the story of Noah’s Ark through the eyes of Noah’s wife. In this essay, she posits that Genesis inherently lends itself to a queer reading. Reflecting on the disparity between the text and our contemporary understanding of a “traditional” marriage, she points to mentions of unions between human beings and fallen angels that result in giants. “What isn’t possible in an environment like this?” she asks.

Read more in volume 4.

Author photograph by Petra Collins, design by Katherine Messenger

‘We Are All Already Perfect’: A Conversation with Melissa Broder by Becca Kantor

Wild and profound, Melissa Broder’s novel Milk Fed introduces us to Rachel: a woman in her mid-twenties with a judgmental mother, a soulless job at a Los Angeles talent agency, and a fixation on monitoring her calorie intake and remaining thin. At her therapist’s behest, Rachel makes a bulky clay figure to represent her worst fears for her body. The next day, the figure seems to come to life in the form of Miriam, a “zaftig” Orthodox woman who has started to work at Rachel’s favorite frozen yogurt shop. Instead of being repulsed, Rachel feels unexpectedly … lustful.

In this conversation, Broder discusses the impossibility of separating the spiritual and the physical, the true meaning of perfection, and how she uses a “candy coating of humor” to reveal her deepest vulnerabilities.

Read more in volume 5.

Illustration (cropped) by Saul Freedman-Lawson

How to Have a Disagreement Without Having a Fight by S. Bear Bergman, illustrated by Saul Freedman-Lawson

On a closing note: this month can be a difficult time to talk to loved ones. I’m always inspired by S. Bear Bergman’s comic “How to Have a Disagreement Without Having a Fight.” Bergman, an educator and trans activist, gives advice that is gentle, helpful, and funny. And Saul Freedman-Lawson, who “likes to draw excitingly gendered people with big noses,” provides distinctive and gorgeous illustrations.

Read more in volume 6.

Becca Kantor is the editorial director of Jewish Book Council and its annual print literary journal, Paper Brigade. She received a BA in English from the University of Pennsylvania and an MA in creative writing from the University of East Anglia. Becca was awarded a Fulbright fellowship to spend a year in Estonia writing and studying the country’s Jewish history. She lives in Brooklyn.