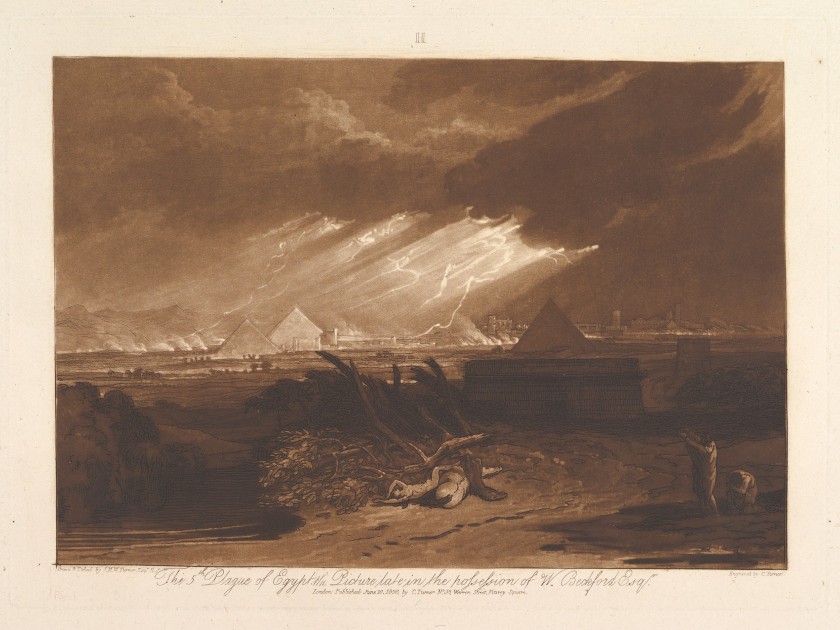

The Fifth Plague of Egypt, part III, plate 16 from “Liber Studiorum,” Designed and etched by Joseph Mallord William Turner, 1808

Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Is there an explanation of the ten plagues that does not include the Divine, but instead stands on science?

This question was asked not only by contemporary academic scholars, historians, and scientists — who used the best contemporary theories to make sense of the biblical account of the plagues — but also by deeply religious Jewish thinkers in the past . One example of this is found in the work of Yehuda Ayyash (1688−1760) who lived in Algiers, where he rose to become rabbi of the city before making his way to Jerusalem. In his commentary on the Passover Haggadah, Ayyash asked why God threatened Pharaoh with the plague of pestilence (dever) using these specific words: “…the hand of the Lord will strike your livestock in the fields” (Exodus 9:3). It would surely have been obvious that livestock, which generally spend time outside in fields, would be smitten with the plague in those same fields. To explain why this location was specifically mentioned, Ayyash reminds his readers of the etiology of plagues — what today we might call their scientific explanations. Plagues were thought to have been caused by foul air, or miasmas, which poisoned those who breathed it in. Therefore, when a plague struck, it was best to flee to a place where the air was clean of these poisonous vapors, and this often meant leaving the confines of one’s home and living in open fields:

It was important to note that in a pandemic [magefah] most of the sickness is caused by poisonous air and foul smells. Therefore, many people flee to the fields and orchards and meadows, open spaces where there is no foul air, but instead the air is pure and clean and sweet…And it is here that the Egyptians were forced to acknowledge the hand of God and his providence, because they realized that these deaths were not natural…for they occurred in the fields and not inside, which is the opposite of what usually happens. This is the hand of God and there is none like Him.

This account was published some two centuries before a rational etiology of the ten plagues became a topic of scientific interest. While this deeply religious approach of Rabbi Ayyash might conflict with the methodology of those who would analyze the words of the Bible through a scientific lens, it demonstrates that even traditional Jews turned to the scientific theories of their time as a starting point for understanding the significance of biblical miracles. Although Ayyash understood the plague of pestilence as a supernatural event and a reversal of the natural order, it could only be comprehended as such using the widely accepted theory of miasmas to explain how it miraculously everted the natural order.

There is a long list of scientific explanations of the ten plagues. For example, in 1957, Greta Hort suggested that the plagues began with silt that was washed into the Nile from one of its flooded tributaries. The river was overrun with bacteria which caused the fish in it to die. As a result, “the frogs would have to leave their normal biotope and seek refuge on dry land.” However, Hort theorizes that the frogs themselves died from anthrax, one of those bacteria that bloomed in the Nile. The plague of “lice” was actually a mosquito infestation, and the fourth plague, a swarming of fleas, “is the sudden mass multiplication of some insect or other and its just as sudden disappearance, as it is known to everyone who has lived for any length of time in tropical or subtropical regions.” The decimation of the cattle was caused by their ingesting fodder contaminated with the same anthrax that killed off the frogs. When the anthrax bacillus later infected the Egyptians, it caused the skin pustules described in the sixth plague. Hort’s series of unfortunate events stops at this plague; she postulated that the last four plagues were not interconnected.

Despite the importance of the plagues to the Exodus story, nowhere in the Bible is it listed that there are only ten of them.

Alternatively, perhaps microbes were responsible for the plagues. One possibility is a tiny single-celled protozoon which goes by the scientific name of Trypanosoma evans and which causes disease in cattle; another suspect is the rove beetle, which produces a blister-inducing toxin. Perhaps molds played a part. They would have grown quickly in the wet and humid conditions of Egypt’s grain stores, and here they could have released dangerous mycotoxins. In biblical times (and long beyond) firstborn sons were always treated more favorably. Maybe, during the famine that must have followed the previous plagues, any little food that might have remained inside the houses would have been given to the firstborn. This food would have been moldy and toxic in view of the rain, hail, and darkness. In the mold theory, the victims of the tenth plague were killed by the very prejudices of a society that had favored them. Other imaginative explanations have involved volcanoes and climate change.

Despite the importance of the plagues to the Exodus story, nowhere in the Bible is it listed that there are only ten of them. When they are mentioned in the Book of Psalms (which they are, twice), they are reduced to only seven in number. In Psalm 78, no mention is made of lice and darkness; in Psalm 105 darkness is mentioned as the first plague, not the ninth. This suggests that there had been different traditions about both the number and the nature of the plagues, which were later unified in the account found in Exodus. In light of this, it is difficult to give credence to any of the differing attempts to explain the natural causes and order of the ten plagues, no matter how imaginative they are.

Regardless of which of these highly conjectural explanations might be correct, the authors of the Bible would have described the plagues in terms that would resonate with their contemporaries. Those for whom the story was first written would have recognized many features of the plagues described in the Book of Exodus. They would have nodded their heads at the accounts of lice infestations, skin boils, and sudden deaths, for they were also features of their own lived experience. The ten plagues described in Exodus included both natural disasters and epidemics, which, just as they do today, claimed lives in a capricious and random way.

Jeremy Brown is a physician and historian of science and medicine and directs the Office of Emergency Care Research at the National Institutes of Health. His previous books include Influenza: The Hundred-Year Hunt to Cure the Deadliest Disease in History, New Heavens and a New Earth: The Jewish reception of Copernican Thought, Cardiology Emergencies, and as editor, The Oxford American Handbook of Emergency Medicine.