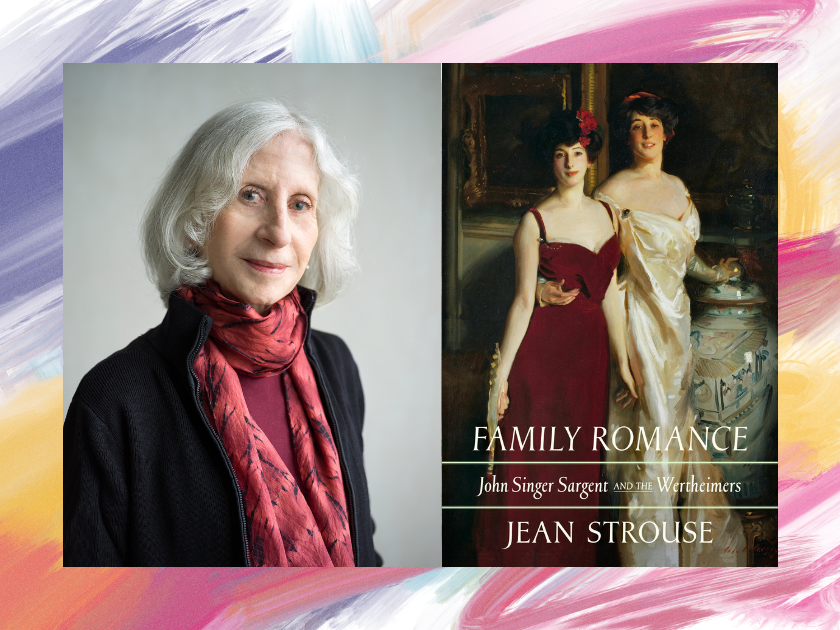

Author photo by Nina Subin

Jean Strouse’s new book, Family Romance, examines the relationship between renowned American expatriate painter John Singer Sargent and his long-standing subjects, the Wertheimer family of England. Strouse delves into Sargent’s twelve iconic portraits of Asher Wertheimer, his wife, and their children, exploring the evolving artistic collaboration and personal bond that spanned decades. The book also situates the Wertheimers and Sargent within the broader cultural and social currents of turn-of-the-century Britain. Strouse’s meticulous research and nuanced analysis shed light on the intersection of art, patronage, and elite society in this period. In the following conversation, Strouse discusses how she came to write the book and some of the dramas, tragedies, and surprises she encountered.

Carol Kaufman: Family Romance is your third book about illustrious Americans with strong ties to England: you’ve written about Alice James, J. Pierpont Morgan, and now John Singer Sargent. What drew you to these particular people?

Jean Strouse: Different things drew me to each of these very different subjects, although you are quite right that all three were Americans who either lived or spent a great deal of time in England. And their stories took place over roughly the same period: from about the middle of the nineteenth century into the early twentieth.

The American expatriate artist John Singer Sargent had made cameo appearances in both of my previous books. I had always admired his paintings but knew little about his life. In 2001, a couple of years after my biography of Morgan was published, I happened to see an exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum called “John Singer Sargent: Portraits of the Wertheimer Family.”

I had never heard of the Wertheimers, and learned at the exhibition that the father of the family, Asher Wertheimer, was a prominent London art dealer of German Jewish descent. He and his wife had ten children, and he commissioned Sargent to paint portraits of them all, individually and in groups. All twelve portraits were on view in Seattle, along with photographs, drawings, and documents. In one photo, Sargent stands with two of the Wertheimer men and a couple of other companions on the lawn of the family’s country house outside London, pausing for the picture during a game of croquet. Apparently, artist and patron became warm friends. Sargent was such a frequent dinner guest at the Wertheimers’ London house that the dining room came to be known as “Sargent’s Mess.”

I associated Sargent with portraits of European aristocrats and American elites — not with Jews. Yet here was ample evidence of his work and close engagement with a Jewish family. I was intrigued , but at the time was not looking to write another book. I bought the exhibition catalog, went home to New York, took a full-time job — and continued to think and wonder about all these people, their lives, their friendships, their social worlds. About ten years later, I decided to try to write about them. And now, about ten years after that, the book has just been published!

CK: Congratulations! First, I’d like to ask you about the title. Is “family romance” a nod to Freud, who used that phrase to identify a fantasy he observed in many of his child patients, that their actual parents would be magically replaced by a more loving or higher status set?

JS: Good question. I am familiar with the Freudian use of the term “family romance,” although it is not the intended meaning of this title. Before we had a definite title, I had been thinking of “Portrait of a Family.” However, the book is actually a group portrait, not only of a family but also of an artist, their friendships, and an era of dramatic social change. Which meant that my placeholder idea didn’t work. And my editor wanted something with a bit more zing. Both he and a Sargent expert who helped me a great deal thought the word “romance” would suggest the strong connections among all these characters, and from there we quickly got to “Family Romance.”

As regards the Freudian sense of the term, the fantasy of having “better” parents: both Sargent and Asher Wertheimer came from distinguished families, and both men achieved significant social stature and material success in England. They didn’t need to dream up better lineage. Yet neither an American expatriate nor a family of Jews would ever be fully accepted as “one of us” in British society, and of course there is no way to rule out a fantasy.

CK: I admire the way you developed the story of the friendship between Sargent and the Wertheimers, setting their long, happy, productive relationship against the backdrop of the historical events unfolding around them. Can you describe how you processed and integrated what must have been a tremendous amount of research?

JS: Thank you about the story! The historical and archival material for these relationships was actually quite thin compared to what I had had for my books about the James family and J. P. Morgan. The records of the Wertheimer firm had been lost or destroyed, and there was no great trove of Wertheimer family papers. Luckily, I found a few descendants who did have some material — genealogies, photographs, documents, family stories — and very generously shared it with me. One of them, who was in her nineties when I met her, was the American widow of Asher’s youngest grandson. She had a phenomenal memory, could identify people in photographs, had owned drawings and watercolors that Sargent had given to several of the Wertheimers — and she had photographs of those images on the walls of her house in rural Kent, about an hour from London. I visited her there as often as I could. She died in 2022, alas; I took too long to write this book!

Sargent was an excellent, witty writer, although mostly of notes rather than discursive letters. Like the Wertheimers, he did not keep diaries or financial records, and his correspondence was scattered all over the world. I was extremely lucky in that regard as well, however. Two of the leading authorities on Sargent, Richard Ormond (the artist’s great-nephew) and Elaine Kilmurray, were extraordinarily helpful to me throughout this process. They introduced me to other experts, directed me to relevant letters, and unfailingly answered my novice questions. Richard invited me to read photocopies of Sargent letters in his Bloomsbury studio. Elaine, who is among many other things a wizard at deciphering Sargent’s impossible scrawl, especially when he is writing in French, gave me the benefit of her long experience as I slowly learned to make out those scrawls for myself.

CK: In the introduction, you mention that you own a cache of Sargent’s letters. How did that come to be?

JS: It’s a long story; I’ll try to keep it short. Early on in my interest in these people, I learned that one of the Wertheimer descendants had sold a packet of Sargent letters, mostly written to the eldest Wertheimer daughter, Ena (short for Helena), through Sotheby’s. I wrote to Sotheby’s, who kindly put me in touch with the buyer, an American art dealer. I told him about my book and said I would love to see the letters. He asked if I would transcribe them for him; he did not explain why, but as I said a minute ago, Sargent’s handwriting is extremely difficult to decipher, and I realized that this dealer probably could not read it. He sent me Xerox copies of about forty letters and notes. I transcribed them, sent him the transcripts — and then realized that he was going to sell the letters with my transcripts. Too late! I couldn’t very well take them back; and I was grateful to have read the photocopies.

For a long time there was no word of a sale. Another Sargent dealer told me that the owner of the letters was waiting until my book came out, since that might create a market. A few years later I learned that a packet of Sargent letters, with transcripts, was coming up for auction in Maine. From the auction house website, I could see that they were his letters to Wertheimers and the transcripts were mine. It turned out that the owner of the letters had died; his estate was selling them.

I registered for the auction. On the appointed day, I bid the floor price, got raised once, and acquired the letters! Although I had already read the photocopies, some of them were not very clear, and most had been separated from their envelopes, which help with dating. Sargent rarely noted the date on his correspondence. Having the actual letters in my hands — vivid “conversations” between Sargent, Ena, and a few other Wertheimers — was thrilling!

CK: Antisemitism is a throughline in the history you relate. Were you surprised by the Jew-hatred that you discovered in your research?

JS: Yes, probably naively. The Wertheimer paintings have served as cultural Rorschach tests for 100 years: they elicited warm praise in some quarters — and venomous attacks in others. An American who saw the unfinished painting of Asher in Sargent’s studio in 1897 said that the art dealer, holding a cigar in one hand, looked as if he were “pleasantly engaged in counting golden shekels.”

Asher left nine of the paintings to London’s National Gallery, and when they were put on display there in 1923, a committee in Parliament held a debate about them. One MP asked the head of the committee if he could not arrange for “these clever, but extremely repulsive, pictures [to] be placed in a special chamber of horrors, and not between the brilliant examples of the art of Turner?”

CK: Chilling words. There are many more examples throughout the book. It’s hard not to notice how important acquiring art masterpieces and country houses was for the Wertheimers and their cohort of wealthy British Jewish families. Most of these families, including most of the Wertheimer children, eventually repudiated their religion, although Asher remained a self-confident Jew. Do you think these two tendencies — amassing impressive possessions and abandoning Judaism — were connected, perhaps stemming from feelings of being othered and rejected by non-Jews in both England and America?

JS: No doubt. However, it is also true that many of these discerning collectors and home owners genuinely loved art and architectural beauty.

CK: I love the pithy quotes that enliven the book, such as Pablo Picasso’s response to some of Gertrude Stein’s friends when they objected that she didn’t look like his 1906 portrait of her. You write, “He is said to have replied, accurately, ‘She will.’” Sargent himself came up with a number of noteworthy lines. Can you cite an example or two of his memorable remarks?

JS: While he worked on Asher’s large commission between 1897 and 1908, the painter mock-complained to another friend of being in a state of “chronic Wertheimerism.” He once wrote to Ena, “Why won’t some of my sitters’ portraits get finished? I’ve tried giving my nephews’ mumps to some of them.” And he sounded somewhat like his London neighbor Oscar Wilde when he sighed to a friend, “What a tiresome thing a perfectly clear symbol would be.”

CK: You write that the novelist Henry James and Sargent “both drew indelible portraits of women,” and that an acquaintance of James noted that James “seemed to look at women rather as women looked at them. Women look at women as persons; men look at them as women.” Do you, and did critics in Sargent’s day, view him as a particularly perceptive painter of portraits of women?

JS: Absolutely. Some of his finest were of the Wertheimer daughters and Sybil Sassoon, another of his good (Jewish) friends. On seeing the artist’s portrait of Sybil’s mother, Lady Sassoon — the former Aline de Rothschild — at London’s Royal Academy in 1907, one visitor said to his companion: “[Sargent] paints nothing but Jews and Jewesses now and says he prefers them, as they have more life and movement than our English women.” That life and movement are especially vivid in the portrait of Ena and Betty, Daughters of Asher and Mrs. Wertheimer.

CK: I imagine that researching the book took you to a lot of wonderful places. Did you have a favorite or two?

JS: Mostly it took me to England, which I always love to visit. In this case, London, Buckinghamshire, and Kent. Other great places I “had” to visit for this project were Berlin and Vienna. Not complaining!

Carol is the executive editor of Jewish Book Council. She joined the JBC as the editor of Jewish Book World in 2003, shortly after her son’s bar mitzvah. Before having a family she held positions as an editor and copywriter and is the author of two books on tennis and other racquet sports. She is a native New Yorker and a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania with a BA and MA in English.