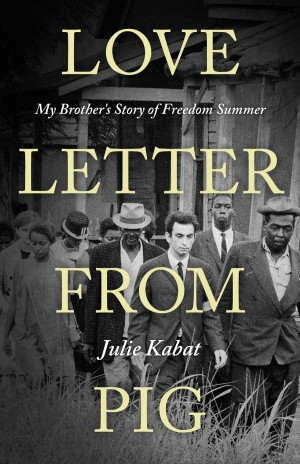

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Marc Dollinger is the author of Black Power, Jewish Politics: Reinventing the Alliance in the 1960s (Brandeis University Press). He is blogging here as part of Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

Since the end of World War II, American Jews and African Americans have journeyed through more than 75 years of inspiring political alliances that brought national attention to Jim Crow segregation, witnessed Jewish participation in some of the most dangerous civil rights actions of the 1950s and 1960s, and celebrated monumental legislative victories in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The relationship has also suffered fractures. When black nationalists rallied around the emerging Black Power movement, they pressed whites, meaning Jews, to the margins of their organizations’ leadership. Anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic statements from some blacks alienated Jewish leaders while Jewish racism undermined African American confidence in the strength of white liberalism to get the job done. For most observers, the black-Jewish alliance started with a strong spirit of consensus, only to suffer when the radical politics of the late 1960s balkanized ethnic and racial groups across the American political landscape. A closer examination, though, reveals a far more optimistic, if surprising, story.

Between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s, a time civil rights historian Murray Friedman called “the golden age” of the black-Jewish alliance, the two groups celebrated the hope and optimism of the Cold War consensus. Blacks and Jews forged interracial alliances while religious leaders across the Protestant-Catholic-Jew triad advanced interfaith dialogue, all part of the larger effort to promote the United States as a center of democracy, pluralism, and opportunity for all. With these efforts, Americans across the political spectrum aspired to realize the nation’s dictum: E Pluribus Unum, from many, one.

When President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, the legal separation of the races ended. In the years that followed, many white liberals paused their civil rights efforts, cheering their legislative achievements. While African American civil rights workers celebrated a hard-earned victory, they also understood that the most challenging work, fighting the institutional racism woven into the very fabric of American society, remained. They tended to look with even greater skepticism at white, and Jewish resolve. After a series of high-profile altercations throughout the mid-1960s, the black-Jewish alliance seemed to break, with each side tending to its own group’s needs.

Contrary to conventional thinking, though, the end of the black-Jewish alliance and rise of black militancy did not end the interracial consensus. It simply redefined it for a new identity-politics based era. At the very time when the two communities split over fundamental differences in political approaches and strategies, Jewish leaders sensed opportunities to leverage Black Power thinking to strengthen Jewish education, identity, and political activism. When young progressive Jews faced rebuke from black militants intent on maintaining African American leadership of civil rights organizations, they responded by borrowing a page from the Black Power handbook. Across the Jewish communal landscape, young Jews turned inward.

Jewish leaders and organizations offered strong and public support for Black Power. In 1968, the American Jewish Committee praised Black Power for its emphasis on “black initiative, black self-worth, black identity, black pride.” Philadelphia’s Rabbi Dov Peretz Elkins, playing on the popular “Black is beautiful” slogan, assured his congregants that “we have always felt that Jewish is ‘beautiful.’” Boston’s famed rabbi Roland Gittelsohn, a member of President Harry S. Truman’s presidential civil rights commission, argued “the positive aspect of black power is its search for ethnic identity. This, we Jews of all peoples should be able to understand and approve. The American Negro today is in this respect retracing precisely the experience of American Jews a generation or two ago.”

American Jews internalized Black Power’s message in a host of new Jewish-centered initiatives. One quarter of the activists in the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry earned their training in the civil rights movement. Its leader Jacob Birnbaum proclaimed, “Many young Jews today forget that if injustice cannot be condoned in Selma, USA, neither must it be overlooked in Kiev, USSR.” When the State of Israel earned a dramatic military victory in the 1967 Six Day War, American Jews, buoyed by the rise of black nationalism, surprised even their own communal leaders with their newfound Zionist activism. Giving to Israel-related funds doubled the year after the war while some 7,500 students gathered their passports and traveled to Israel to lend their support. As Gittelsohn claimed, “The Black Power advocate is the Negro’s Zionist. Africa is his Israel.”

As African Americans rediscovered their ancestral homelands with African dress, names, style, and culture, so too did the Jews. “The Jewish Catalog,” a 1960s-inspired “how to” volume that taught otherwise assimilated Jews how to return to tradition, emerged as the Jewish Publication Society’s second-best selling book. Only copies of the Hebrew Bible outpaced its sales. Even right-leaning Jews joined the new militant consensus as Meir Kahane’s Jewish Defense League emulated Black Power ideology in its calls for greater Jewish activism.

The “alliance go smash” model that periodized black-Jewish relations as warm and welcoming from 1954 – 1964 only to be ruined with the rise of Black Power fails to account for a powerful new consensus that brought Jews and blacks back together again. Even as the two groups appeared separate, divided, and even antagonistic towards one another, they still walked down the same identity-politics inspired path together. Sometimes, outward difference masks internal consensus.

Dr. Marc Dollinger holds the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies and Social Responsibility at San Francisco State University.He has served as research fellow at Princeton University’s Center for the Study of Religion as well as the Andrew W. Mellon Post-doctoral Fellow and Lecturer in the Humanities at Bryn Mawr College, where he coordinated the program in Jewish Studies.He is author of Quest For Inclusion: Jews and Liberalism In Modern America published by Princeton University Press, California Jews, co-edited with Ava Kahn, and American Jewish History: A Primary Source Reader, both published by Brandeis University Press.