This piece is part of our Witnessing series, which shares pieces from Israeli authors and authors in Israel, as well as the experiences of Jewish writers around the globe in the aftermath of October 7th.

It is critical to understand history not just through the books that will be written later, but also through the first-hand testimonies and real-time accounting of events as they occur. At Jewish Book Council, we understand the value of these written testimonials and of sharing these individual experiences. It’s more important now than ever to give space to these voices and narratives.

In collaboration with the Jewish Book Council, JBI is recording these pieces to increase the accessibility of these accounts for individuals who are blind, have low vision or are print disabled.

In Katherine Mansfield’s The Garden Party (1922), Laura Sheridan describes a flurry of preparation in the garden much the same way as a movie scene is staged. Table decorations are placed just so. Seconds before the first person appears, the host, with a glare, signals a veritable “rolling!”, and everyone knows not to touch a thing until the guests do.

The preparations for my twins’ second birthday party followed a similar course. The party menu was a talking point that lasted for weeks, months, even years after the event. Only adults would have appreciated the intricate styling; prepared by my perfectionist mother, each bespoke slice, sandwich, and spread was extravagant. I stayed up until two am on the morning of the party, cutting cookie dough into the Hebrew initials of each of my children.

I had bought the aleph bet cookie cutters while living in Tel Aviv, before the kids were even born. Examining them back in Melbourne, they seemed even more exquisite; each a contortion of precious metal holding its own story. The cookies they formed were like artifacts, each topped with butter icing.

For the next decade in fact, that second birthday party would be the culinary marker, never quite attained again, though not for lack of trying. Birthdays were a big deal in my house; preparations would start six months before the day itself. There would be edible beehives and kangaroo cakes, roller-skate parties and bush walks. Yet the aleph bet cookies would not appear again; they were lost to one of several toy boxes full of game parts and puzzle pieces.

Then came Covid-19 and its aftermath. More parties and milestones cancelled. There would be no bar mitzvah. I reread The Plague by Albert Camus and told myself the worst was actually happening; that we did indeed live in times so interesting that the phrase had become outdated.

Jump forward another three years and talk of birthday parties had dwindled to a virtual halt. Now I would be the one pleading, begging — “Please, can I bake you a cake? Any cake. Any shape at all! Which one do you want? Please, have a party and invite whoever you like. What should I book? A restaurant? A movie? Anything.” Words fell in vain on the floor, as they had the year before and the year before that. I began to yearn for the past and for the person laboring with dedication and delirium all through the night, icing cupcakes and wrapping party favors.

The rabbis say we leave with questions and return with answers. I was mired in queries, like an ellipsis. Soon their sixteenth birthday was around the corner.

Ever since their birth, I had not missed a birthday. I’m not sure if that was a goal or a coincidence, but that’s the way things were. So when it suddenly became apparent that I might indeed miss their sixteenth, I awoke from my fog of never-ending questions on rotation. I realised that if I were to preserve any semblance of birthday customs, I would need to rethink my previously-booked overseas research trip.

But, a superstitious fatalist at heart, I wasn’t comfortable tampering with pre-booked dates.One day, during an intense planning period of academic research and travel, I woke up and decided that being home for my children’s birthday was still important, even more so than being home for Rosh Hashanah, which was taking place at around the same time. Within hours, I rejiggered my accommodations, meetings and appointments. It all seemed to happen so easily, it felt almost preordained in itself. I look back on that time with goosebumps as I swallow the global changes and I realize what would soon come to pass. I brace myself for each new day in a world that has since been overcome with untenable anxiety and violence of war.

“Why don’t you stay longer — a few more days?” people asked me, as I raced around South Africa and Eswatini, spending tireless hours with my back arched over dusty archives, trying to stretch the days so that they would accommodate one more tour, one more interview, one more site visit. I managed to arrange it so that I would arrive home just in time — the night before their birthdays. My plane landed in Melbourne at half-past nine in the evening. I had already prepared everything for the next day’s celebrations. My children had allotted me a two-hour stretch over lunch, after which they intended to return to their real birthday celebration, involving a house full of raucous teenagers. I opened the front door, dropped my bags in a heap, and raced to see my children’s fifteen-year-old faces one more time.

On the morning of birthday number sixteen, I had begun to question my choices as my eyes remained cemented shut — equal parts jetlag and adrenalin. By the time lunch was upon me, I was standing in what sounded like a full barn, wooden walls bulging close to bursting with the cacophony of a full string orchestra, the drummer performing on my head. Conversation was difficult. I mistakenly ordered a whole bottle of champagne instead of a glass, and went in search of other partakers of liquid lunches. The two hours my children had gifted me could not have passed quickly enough. Finally, I ended up where I needed to be — on my couch, head throbbing, legs up. As the afternoon dwindled into evening, I lay there, determined to stay awake until ten o’clock, at least. Midnight would be too ambitious.

__________

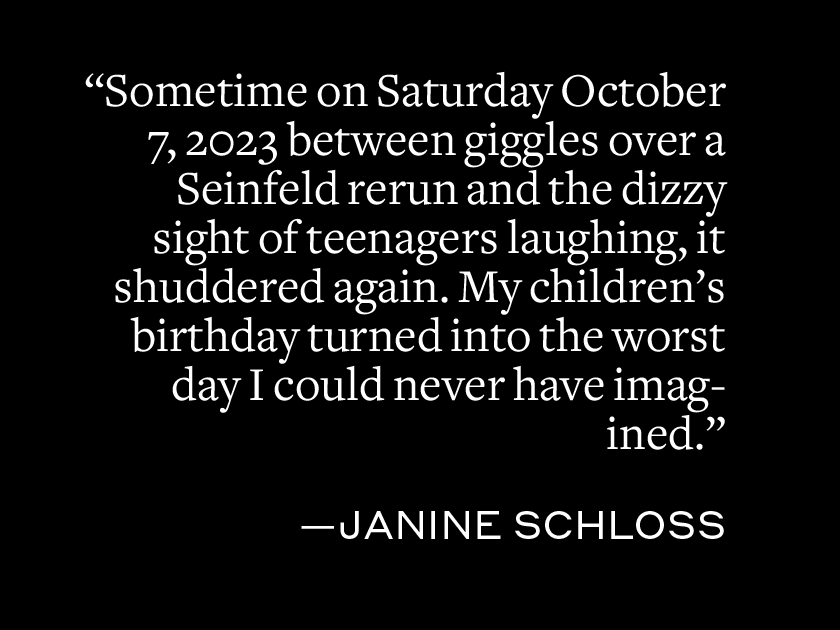

My world first shuddered off when my mother died suddenly on Monday February 17, 2014. Sometime on Saturday October 7, 2023 between giggles over a Seinfeld rerun and the dizzy sight of teenagers laughing, it shuddered again. My children’s birthday turned into the worst day I could never have imagined. I spent the next few hours stuck to my phone as text messages bounced in from Tel Aviv. It took me several hours to comprehend that the fragmented news heralded an historic change.

In ways that do not make any sense temporally or emotionally, it’s still my children’s sixteenth birthday on October 7, 2023. It has been the longest birthday. It’s one I want to rip out of time and throw so far away it forgets its purpose as a day in the calendar.

I tell them—This is not your birthday anymore.. Let’s forget this one. And next year…we will change the date. Make it go away, the bloody footage that agonises through the hours and minutes and seconds of that day, is the one continuing on, still rolling on screen. It is still today. The longest day. I tell them — this is not about you, or me or us. This is a day of mourning which is etched eternally — no cookie cutter to offer a feelgood metaphor. This is a day when all the bridges between our today and our yesterday and our yesteryear have been burnt, as Stefan Zweig lamented. I It is a day when the unspeakable past began screaming in deafening tones, its noise causing even more pain than the silence. It is a day when I went from pondering words like ‘testimony’ and ‘witness’, in terms of the past, to leaping along with them into the present, as if I have, together with these words, cracked through time and back again. Yesterday I was someone who spent endless hours looking back — as far back into the past as my spade could excavate, determined to keep digging until I reached myself once more. Today I want to close my eyes for fear of what I will find. All the parts have been confused and jumbled into one box of time, missing or broken, like the contents of toy boxes my children once had in their playroom. Trying to fit the pieces together is futile; they make no sense anymore. Metaphors sound shallow; comparisons are incomprehensible. It’s not about me or us or cake. Every corner collects more debris of a shattered story in time. What do we do with the pieces? How do we label them now? The era of the witness was a closed chapter yesterday. Where do we put what we’ve witnessed? The words slip in so easily — but then slip away. Where does anything belong, now that the words have been mixed up, become illegible on pages ripped up and spat out? It will be tomorrow, I tell my children. But not today.

I think of Katherine Mansfield again. For decades, that vision of the party in disarray had drifted back into my thoughts at times when I had been troubled by the chaos of my own life:

The ribbons and the roses were all pulled untied. The little red table napkins lay on the floor, all the shining plates were dirty and all the winking glasses. The lovely food that the man had trimmed was all thrown about, and there were bones and bits and fruit peels and shells everywhere. There was even a bottle lying down with stuff coming out of it onto the cloth and nobody stood it up again.

The imagery of birthday mess is shredded of all meaning, along with everything else; “mess” sounds like a conceited description now. The phrasing, once poignant and piercing, is not so today:

“And the little pink house with the snow roof and the green windows was broken — broken — half melted away in the centre of the table.”

“Today is a new type of broken”, I tell them. Today is not about us.

“But if not us, who?”

Today, nothing matters anymore, and everything does. The world has inched further from itself.There are too many questions, and yesterday has burnt all of the answers. But tomorrow is still coming.

References

Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Mansfield, Katherine. Bliss and Other Stories. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1920.

The Garden Party and Other Stories. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1922.

Wieviorka, Annette. Th Era of the Witness. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006.

The Western Daily Press. ‘Mr Chamberlain at Liverpool: A Series of Speeches, Patriotism Still a Live Force’. Bristol, England, January 21, 1898.

Zweig, Stefan. The World of Yesterday. London: Cassell and Company, 1947.

The views and opinions expressed above are those of the author, based on their observations and experiences.

Support the work of Jewish Book Council and become a member today.

Janine Schloss was born in South Africa and immigrated to Australia in 1981 with her parents and brother. She has an Honours degree in English. She lived in Tel Aviv for three years, between 2005 and 2008, during which time her children were born. She is currently undertaking a PhD in Jewish cultural practice via the Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation at Monash University. She is also a Program Manager for Melbourne Jewish Book Week. She lives in Melbourne, Australia with her partner and two children.