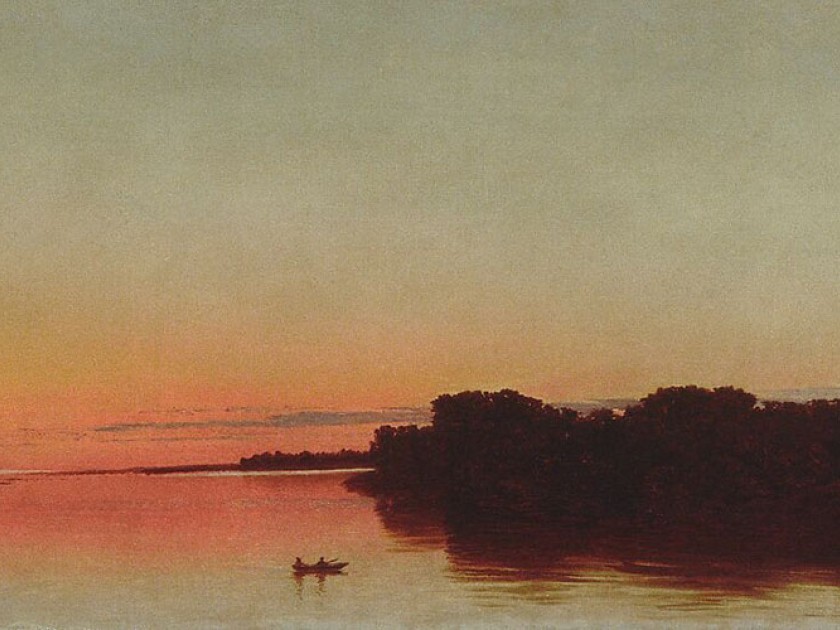

Twilight on the Sound, Darien, Connecticut by John Frederick Kensett, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Thomas Kensett, 1874

Friday nights were reserved for Shabbat dinner with Mama Fortunée. That was the deal in my family when I was growing up, for as long as I could remember. No sleepovers, no plans with friends — not on Friday nights, when we would make the drive from our house in Westchester County to hers in Glen Cove, a small city across Long Island Sound.

Mama Fortunée was what we called my grandmother, whose Arabic name, Mas’ouda, meant the same good fortune as it did in French. She was forty-one years old when she left Baghdad — where she was born and where our Jewish family lineage reached back some two thousand years — for the United States in 1972, along with my grandfather, my mother, my aunt, and my uncle. Resettled in Queens as refugees, they moved to Glen Cove a few years later. Much of the rest of our extended family scattered across Long Island. It must have been jarring, for a family that only ever knew a fertile stretch of desert between two rivers, to live so close to the sea.

The journey to Glen Cove felt like a pilgrimage of sorts. After school, my mom would drive us down the Hutchinson River Parkway and across the Whitestone Bridge, passing high above the blue, glimmering water. We’d pick up my dad at a shopping center near his work in Queens, and continue via the Cross Island Parkway, the Long Island Expressway, and Glen Cove Road, until we reached Mama Fortunée’s little white house on a quiet, curved street. It had thick, dusty carpets, and the cushions on the old dining-room chairs were still wrapped in the plastic packaging from the furniture store. There was a large, windowed den where Jews from the old country would set up folding chairs and gather together to jabber away about a place we kids had never been, and a home we would never know, in a Jewish dialect of Arabic that we would never understand.

There was always traffic on the drive to Mama Fortunée’s house. A distance that was only six miles as the crow flies could take an hour or even two by car. “If only there was a boat,” we grumbled, mostly in a joking way, on some of those nights. “If only there was a boat, we could just zip across the water!” One sticky Friday in July we were stuck in such a standstill that my parents turned off the car in the middle of the expressway. Surely my brothers and I had been fighting in the broiling backseat, because when my mother noticed an ice-cream truck idling one lane over, we all ended up with popsicles passed through the open windows.

In high school, I did buy a boat, a cheap yellow kayak from Walmart. I began exploring the Long Island Sound — mostly around the Bronx and New Rochelle, near where I lived, and around Glen Cove, where Mama Fortunée did. She did not like the idea of a kayak, not in New York, at least. “He is too far away!” she would exclaim to my mother in her singsong Arabic-accented English as they waited in the parking lot, watching me from the shore. “Where is he going? Why is he leaving?”

Actually, I was never really leaving. Mine were roundtrips; I always returned to the land wherever I put in. But each year brought new discoveries, and the journeys grew longer. In the summer, if I stayed out until dusk, golden sunsets backlit the Manhattan skyline, and charcoal smoke rose from the city parks where Latin American families grilled dinner. In the winter, there were seals. From my vantage point, drifting on the water, you could make out the stately mansions on Glen Cove’s coastline, scattered amid green forests. Mama Fortunée’s house, smaller and further inland, suddenly did not seem that far away.

Meanwhile, we continued — week after week, year after year — to drive there on Friday evenings. At dinner, my older cousin Daniel would say the kiddush, standing in the place of my late grandfather Papa Jamil, who had done so until he died suddenly when I was a toddler. (Papa Jamil always wore suits, even while gardening, and said his prayers with a torn and musty siddur in one hand and one of his baby grandchildren nestled in his other arm.) We recited the words aloud together even though most of us did not understand what they meant. But we were, in a single act, holding onto something. Mama Fortunée spent hours preparing those dinners. For the adults, she made Iraqi dishes: kubba in pink beet sauce, fried sambousek with chickpea and cumin filling, and t’beet, the traditional Baghdadi Shabbat meal of stuffed chicken slow-cooked in a pot with rice. For the kids, she ordered Chinese takeout, knowing it was what we preferred. Kubba shwandar and General Tso’s chicken sat side by side on the table.

One night, when I was around ten years old, a rare, unexpected tornado swept through the area just as we were about to leave. My father and I were already in the car when it struck, along with torrential rains and flashes of lightning. We could hear old trees cracking and falling around us in the dark. Finally we dashed for the house, slamming the door shut behind us. As we sat on blanket-covered radiators to dry up in the warmth, Mama Fortunée encouraged us to stay.

As the years wore on, and Mama Fortunée grew older, the dinners grew smaller. Her siblings, in-laws, and friends were retreating into the solitude of old age, and suddenly I could count on one hand the number of people around me who spoke Judeo-Arabic — that strange, almost biblical-sounding language that I used to hear so often. Mama Fortunée cooked less and less. One day, we found plastic wrap baked inside the t’beet, and while we said nothing of the discovery, now I realize that she stopped preparing food after that. Instead, we brought takeout containers of kebabs and rice from a Persian grill down the road. “Did you remember the Chinese food?” she’d ask, but by then my brothers and I were grown and wished she could still make the old Iraqi dishes that we’d hardly ever tried, but that now, like so much else, reminded us of home. By the time she turned ninety, my grandmother needed constant care, and we visited her far more often than once a week to make sure she had what she needed. We drove her to the beach so she could watch the water and the gulls.

Sometime around then, late in the summer of 2022, I decided I would make the crossing while she was still alive. I set out on a Friday afternoon around 4:00, as we always had. The sun was shining and the weather was calm. I put in at Larchmont, lifting my yellow kayak over a retaining wall to reach the water, and figured on two hours for the six-mile ride.

But as soon as I left the protected harbor, the wind picked up from the east. The Sound is like a funnel for an easterly wind, and the swells came up sideways against my kayak, knocking pools of water into the boat. By the time I realized the full extent of the trouble I’d gotten myself into, I was too far to turn around. Speedboats and jet skis mistook my frantic gestures for waves hello. I had a life vest, a whistle, and a phone — my family was tracking my location from the shore — but midway across the water I lost reception. For an hour or more, I was alone in the waves and the wind. Glimpsing the Whitestone Bridge in the distance, for once I wished I was on it — wished I was a kid again, along for the ride.

By the time I neared Hempstead Harbor and Glen Cove, the swells began to lessen. A fishing boat called The Klondike called out over their loudspeaker to ask if I needed rescue, but I waved them off, confident that the worst had passed. At nightfall I made it to the Glen Cove shore, but I knew my grandmother would be asleep by then. The world seemed fragile, and as I stepped onto land I found that I was shaking, unsure whether from physical exhaustion or from fright. I found myself reciting the kiddush from memory that night, alone on the drive home.

Jordan Salama is a writer whose work appears in National Geographic, New York Magazine, The New York Times, and other publications. An American writer of Argentine, Syrian, and Iraqi Jewish descent, he is most recently the author of Stranger in the Desert: A Family Story.