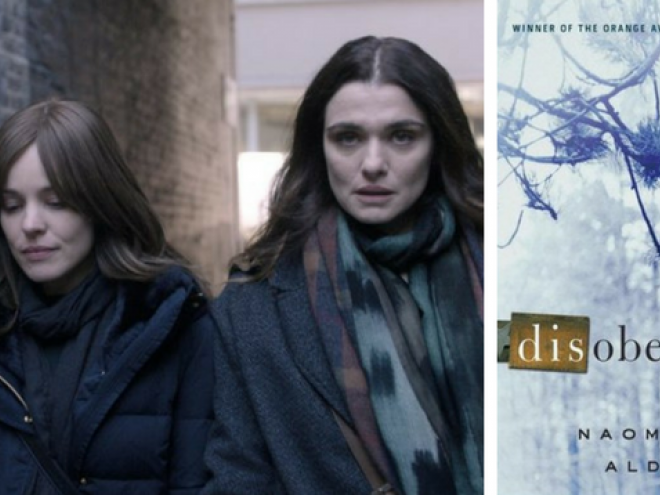

What is “dissed” in Disobedience is obedience— but not completely. Naomi Alderman’s prize-winning first novel (Orange Prize for Fiction) challenges rigid religious authority by having its heroine assert her individual freedom, but then softens that assertion by having her realize how obedience to tradition can restore peace of mind within the frenzied modern West. Ronit Krushka is the lesbian daughter of a venerated London Rav, who returns from America to attend his funeral in the Orthodox Hendon neighborhood. For her, no dichotomies are absolute. Ronit is gay, but is having an affair with a married American Christian man; she is a free, high-powered corporate functionary, but she feels more free observing Shabbat in the semi-shtetl that is Hendon. Her girlhood lesbian lover, Esti, is married to Dovid, the Rav’s rabbinic heir apparent, but both husband and wife implicitly accept Esti’s divergent sexuality.

Obedience is told in three voices: a composite voice of traditional Judaism opens chapters and expounds passages of Torah, a ubiquitous narrator applies the religious texts to the developing story, and Ronit’s own first-person Americanized voice registers, sometimes satirically, her conflict with Orthodox temple politics. “[G]ayness, Jewishness” she tells us, “ — are invisible.” They can be “outed” or kept hidden as the individual chooses. Alderman celebrates the ambiguity of the name “Israel,” as eternal fighting with or for God. And God is seen as enjoying the Jews’ struggle. Plot resolutions — whether Ronit can attend the hesped honoring the Rav’s life or lesbian Esti can function as rebbitzin—are foreshadowed to build suspense, and the contrasting narrative viewpoints implicate the reader in the unraveling. Ronit’s voice is lively; the ubiquitous narrator’s sometimes trips into stereotype. Disobedience, like The Chosen, Brick Lane, and The Kite Runner, probes the fissure between tribalism and pluralism, but with a learned Jewish wistfulness most readers will enjoy.

Naomi Alderman On…

The Biggest Challenges of Writing Fiction

The crippling self-doubt, probably. The sense that the book is never, quite, what you imagined it to be in the first instant it screeched, white-hot, into your brain from wherever-it-is that books come from. It is quite isolating. But there’s a peace to be found on the page as well as a kind of insanity. Like all places to live, it has its advantages and disadvantages.

How She Writes

A laptop but no internet. The internet is deadly though so seductive with its ease of research. So easy to spend hours finding out useful and interesting things and doing no work at all. As for where: anywhere with natural light and no music. Libraries are particularly conducive. I feel I can almost hear the books mating in the background, encouraging me to produce my own baby volume.

Being a Rohr Finalist and Being a Part of a Community of Writers

One of the joys of being involved in this prize is to discover some truly wonderful international Jewish writers — the vibrancy and diversity are astonishing.

It’s really an honour to be part of a community of writers and something that I’m very keen to participate in. Writers tend, by our nature, to work alone. Living in Britain, which has a small Jewish community and where we tend, I’m afraid, to celebrate Israeli and US Jewish cultural achievements above the homegrown variety, does make me feel quite isolated. The idea of being part of a growing, learning, developing community of Jewish writers is, quite frankly, exactly what I need.