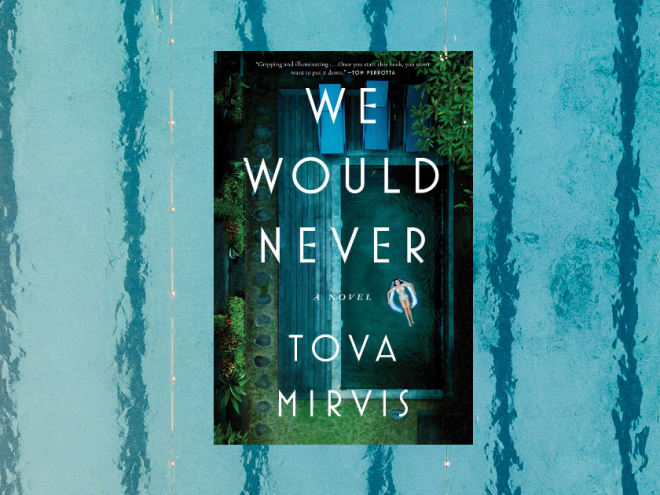

Inspired by a true scandal, Tova Mirvis’ latest novel reveals how a contentious divorce spirals into a nightmarish murder case. The book alternates between the aftermath — a murky, anxious present where the victim’s wife, Haley, and daughter, Maya, are in hiding — and the past, rewinding to show how a nice upper-middle-class Florida family became a tabloid headline.

A deft perspective shift early on asserts authorial control, pulling us in with high stakes and a brisk pace. Yet that thriller-like grip loosens as the novel pivots to the unraveling of a family and the emotional forces that drive good people toward violence. The trend of mislabeling books as part-thriller or mystery for commercial appeal (and the hope of a streaming deal) is increasingly common, but Mirvis’ latest is, at its core, a steady-pulse novel. It doesn’t make you sweat over whodunit or strain to decode its themes — namely, the dangers of all-consuming family love. Even its title, We Would Never, playfully gives itself away (We—in fact—would).

The family at the novel’s center is Jewish, though loosely practicing. The most overtly “Jewish” aspect of the novel may be its overbearing matriarch, Sherry, who is refreshingly portrayed as more than a stereotype or a veneration-tinged punchline akin to the job interview response: “I just work too hard!” — in this case, “I just love too much!”

Instead, We Would Never forces us to look so closely at this kind of smother-love that we cringe. We wince at the neediness, selfishness, and self-delusion fueling it — or, kindlier, at the wounds, as the novel reminds us. Mirvis stirs empathy for her least redeemable characters by alluding to unfillable voids left by upbringings, offering some of her most effective prose (when Sherry becomes an empty nester, the house feels “desiccated”).

As divorce negotiations between Team Haley and Team Jonah give way to manipulation and bribery, an amicable resolution feels inconceivable. Amid the scheming that careens us toward catastrophe, the smallest, quietest presence — young Maya — emerges as the novel’s most tragic casualty. Unfortunately, Maya’s sparse presence in the book also makes her feel unreal as a character — underscoring how preoccupation itself can be a form of neglect.

If there’s a moment when we respect Sherry’s mother-cub stance, it’s fleeting. Her proclamations of boundless devotion eventually sound like what they are: unhinged. By the time anyone raises an eyebrow, it’s too late. The sky is darkening, a family is coming apart. All we can do is sit and watch a hungry love spin out of control and — like a tornado — destroy everything in its path.

Daniella Wexler is a Brooklyn-based psychotherapist and freelance editor. A former trade publishing editor, she serves on the Emerging Leaders Council of the Jewish Book Council and offers editing services at DaniellaWexlerEditorial.com.