The story of the Wertheimers, a wealthy, Anglo-Jewish family, and John Singer Sargent, a celebrated American portrait painter, takes place in London at the turn of the (twentieth) century, a time when modernity was confronting old traditions. Could the entailed estates of the British aristocracy only be rescued by American debutantes with big checkbooks (à la Downton Abbey)? Were the Old Masters like Rembrandt and Velasquez to be replaced by the Impressionists? Sargent, for his part, painted recognizable portraits — a tradition supported by the British upper class. Except he was painting Jews. And these Jews — the Wertheimers, the Sassoons, the Meyers, and others — were not portrayed as furtive Shylocks, but as high-society cosmopolitans. The Wertheimer children were part of that first generation of British Jews attending Harrow, Cambridge, and Oxford — the elite schools — even if they had to endure micro- and macro-aggressions. Later generations of Wertheimers married non-Jews, albeit with special dispensations. Ultimately, it’s unclear whether Jews blending in were more alarming than Jews staying apart. Whatever the case, the Wertheimers and their circle were solidly wealthy, which afforded them forbearance when the landed aristocracy was facing foreclosure.

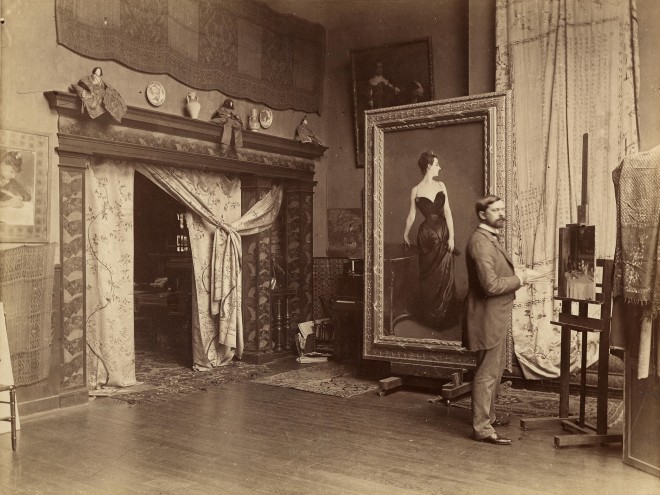

Biographer Jean Strouse and portraitist Sargent pursue parallel missions. Painting the Wertheimers, Sargent highlighted aspects of his subjects that revealed their personalities. His 1898 portrait of the father, Asher Wertheimer, shows him carrying his wealth with audacious confidence. Some of the daughters, Ena and Almina especially, are defiant, lively, idiosyncratic — almost indecorous. Others, like Hylda, are shy and less forthcoming. So evocative are these portraits that Strouse uses them to introduce each Wertheimer to her readers. She notes not just their expressions, but also their fluffy dogs, hairbows, and borrowed gowns. We begin to know them. While there’s not a lot of archival information about them, one at least gets a sense of how, as a family, they interacted. Why the book is called a “romance” is a bit unclear; the essential mystery of why Sargent and the Wertheimers were so intimate remains unknown.

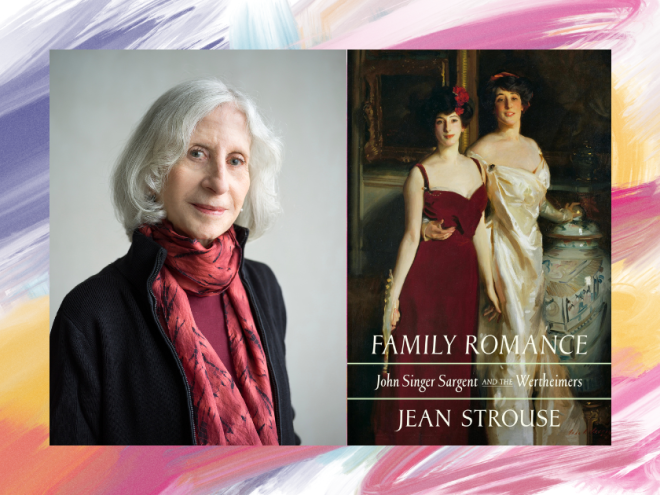

In this compact but lively volume, Strouse relays the stories of Sargent and all the Wertheimers she could track down. She includes three insets of reproductions of Wertheimer portraits, so that readers can see the details she’s describing without consulting outside sources, as well as a list of all of Sargent’s Jewish sitters. By concluding with an account of the modern art world’s appreciation of Sargent, Strouse manages to end on a high note: even if we no longer hear much about the Wertheimers, Sargent is doing better than ever!

Bettina Berch, author of the recent biography, From Hester Street to Hollywood: The Life and Work of Anzia Yezierska, teaches part-time at the Borough of Manhattan Community College.