By

– August 30, 2011

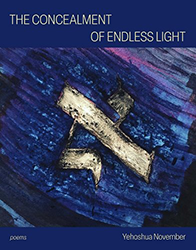

Emily Dickinson once said that she knew she had read a good poem when the hairs on the back of her neck stood up. This did not mean she was getting goose pimples from the thrill of the content. This statement indicated her excitement at having encountered a real work of art — the kind of feeling I imagine prospectors must get when discovering diamonds in a coal mine.

And there are diamonds in this collection of Yehoshua November’s poetry. But it is a different kind of excitement these poems bring, the kind that arises from the recognition of sweetness in certain events of life, which bring a smile to the face and serenity to the heart. One poem is a prime example of this: “In the Unseeable World” a sleepless boy watches his brother reach for a ball in a dream and says, He reaches for nothing/it is all a dream. November compares this to a man passing the window of a shul and, seeing another man swaying and stretching his arms toward heaven, misses the point:

Hashem’s

long arms reach through

the eternal

water and the firmament

and His hands cleave

to the hands of the man who is

praying.

And the man passing by says,

Oh, why does he waste

his energy,

what does he hope to touch?

And there are diamonds in this collection of Yehoshua November’s poetry. But it is a different kind of excitement these poems bring, the kind that arises from the recognition of sweetness in certain events of life, which bring a smile to the face and serenity to the heart. One poem is a prime example of this: “In the Unseeable World” a sleepless boy watches his brother reach for a ball in a dream and says, He reaches for nothing/it is all a dream. November compares this to a man passing the window of a shul and, seeing another man swaying and stretching his arms toward heaven, misses the point:

Hashem’s

long arms reach through

the eternal

water and the firmament

and His hands cleave

to the hands of the man who is

praying.

And the man passing by says,

Oh, why does he waste

his energy,

what does he hope to touch?

It is the mystical belief that fervent prayer reaches God that a pragmatist cannot visualize. And November hints that because of that lack of belief the ordinary man will not be able to reach God or achieve the necessary spirituality to make his life happier. November’s ability to compare belief in an invisible God to the most common experiences is what distinguishes his poems. In “Partners in Creation” he claims that God’s renewal of the world is like the renewal of a child’s world, “when he comes home from school/and his father and mother/still live in the same house,/and he hears them talking at the kitchen table.” (This is a technique used by Dickinson as well when she describes “the busyness in the house/the morning after death” which includes “the sweeping up the heart and putting love away” to be used much later on. The simple household task of sweeping is related to the infinite concept of love throughout eternity.)

And yet, the young poet, November can be irreverent and funny as well. In “Every Friday Night” he describes the sadness of Orthodox Jewish men returning from shul and considers the possible reasons; they may emanate from God’s continuing to conceal Himself but more often than not November feels it is due to “the blond woman/who walks through the mind of every Jewish man/leading him away from his dark-haired wife.” Other poems in this collection are a refreshing tribute to romantic memories connected to his wife.

The impact of November’s poems is a cathartic one. They serve to relieve the tensions of everyday life and leave the reader in a tranquil mood.

And yet, the young poet, November can be irreverent and funny as well. In “Every Friday Night” he describes the sadness of Orthodox Jewish men returning from shul and considers the possible reasons; they may emanate from God’s continuing to conceal Himself but more often than not November feels it is due to “the blond woman/who walks through the mind of every Jewish man/leading him away from his dark-haired wife.” Other poems in this collection are a refreshing tribute to romantic memories connected to his wife.

The impact of November’s poems is a cathartic one. They serve to relieve the tensions of everyday life and leave the reader in a tranquil mood.

Eleanor Ehrenkranz received her Ph.D. from NYU and has taught at Stern College, NYU, Mercy College, and at Pace University. She has lectured widely on Jewish literature and recently published anthology of Jewish poetry, Explaining Life: The Wisdom of Modern Jewish Poetry, 1960 – 2010.