The daughter of an Indian Jain father and an American Jewish mother, writer Diane Mehta has spent a lifetime exploring her identity and searching for meaning in her sometimes painful existence. In this book of kaleidoscopic essays, she digs deep into her past and her family, examining her place in the world.

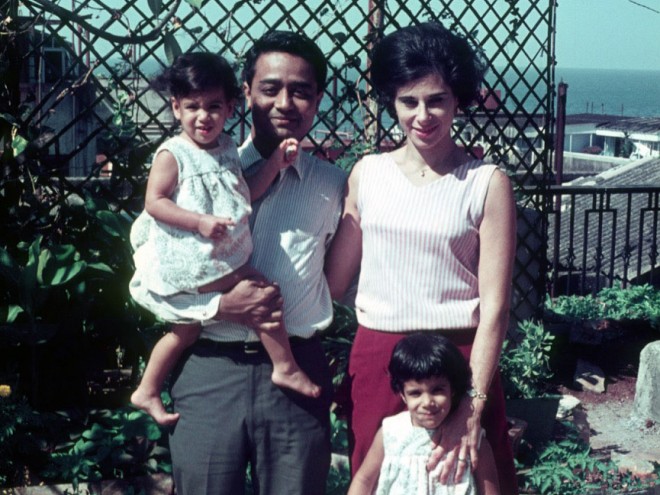

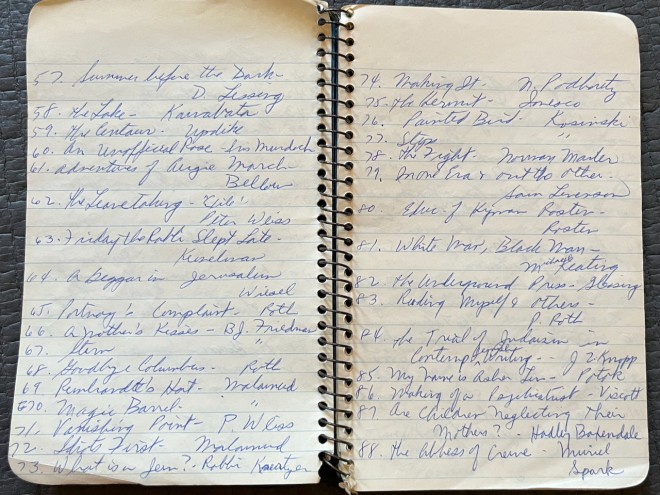

Mehta contrasts the warm, colorful, riotous freedom and sense of belonging she felt among extended family in Bombay, where she spent her early childhood enjoying the privileges of the Anglo-Indian elite, with the cold, sterile suburban New Jersey town where she moved with her family at the age of seven. In America, she was scorned and mocked, a victim of racist and antisemitic taunts. While there is a clear demarcation into before and after, Mehta is too thoughtful to wallow in nostalgia, and scrutinizes her memories alongside the official family documents, photos, and other memorabilia she unearths.

While there is some repetition, since these were originally written as standalone essays requiring backstory, Mehta’s wide-ranging mind keeps the collections from feeling stale or monotonous. With extended riffs on Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, Milton’s Paradise Lost (the source of the book’s title phrase), Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, and classical music, Mehta turns her penetrating eye on anything that captures her interest and can be mined to shed light on the essay’s main topic.

Mehta probes her relationship with her mother, an unfulfilled “surly Brooklyn Jewish intellectual” who suffered from depression, as well as her parents’ unhappy relationship and her own marriage and divorce. She examines her father’s strokes and her mother’s heart condition, along with her own intractable migraines, seeking the meaning of suffering and the value of existence in an unreliable body.

Though not religious or observant herself, as a poet and a student of consciousness, she explores chanting and recitation, Jain and Jewish. Investigating the consolations of prayer and ritual, she explains, “I do not need to believe in God to practice the work of the soul.”

Mehta experiments with form as well as language, with two epistolary essays that offer humorous and unexpected takes on serious subjects. One in the form of a complaint letter to a dog-walking company manages to encompass a profound exploration of her romantic relationship and her chronic health issues. This type of oblique storytelling is also evident in an essay about her abortion of a fetus with Down syndrome, which is related via an extended letter to a pet turtle (which also somehow works).

Mehta is a poet, and not surprisingly, her essays feature poetic and lyrical language, sometimes to the point of inscrutability. This is not necessarily a fault, as she is interested in probing subjects that do not have easy explanations. While discussing her difficulties in school with math and science, she explains, “I was interested in experience, and I could not understand the facts.” This is a useful analogy for her essays, in which she plays with language to illuminate deeper truths. This slim volume is packed with poetic and penetrating insights into the human condition.

Lauren Gilbert is the Director of the Municipal Library of New York City. She was formerly the Director of Public Services at the Center for Jewish History.